SOWING THE SEEDS? PBL IN INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

advertisement

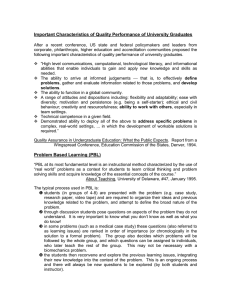

SOWING THE SEEDS? PBL IN INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION Jon A Scaife School of Education, University of Sheffield, 388 Glossop Road, Sheffield S10 2JA, England ABSTRACT Schooling in many developed countries is preoccupied with the inculcation of factual knowledge. There is concern, however, that such knowledge is ill-adapted in contemporary communications-based societies; it lacks applicability, flexibility and durability. Could Problem-based Learning (PBL) provide a radical alternative? Student teachers who gain experience of PBL during their initial professional development will carry messages about PBL into schools and colleges. Innovation is born from seeds such as these. Traditional approaches in initial teacher education (ITE), struggling to keep pace with change, risk falling into an anti-reflexive abyss, telling students to teach towards understanding while failing to model their own messages. This paper explores what PBL can contribute to ITE. It reports how PBL was introduced into an established professional studies programme in an ITE course. The PBL experience is evaluated using a student teacher questionnaire, group feedback, tutor observation and assessment of final project reports. PBL is discussed in terms of its relationship with constructivism and the extent to which its process and purposes in teaching are reflexively related. It is concluded that if certain structural and pedagogic conditions are met, PBL may be highly effective in the initial education of teachers. KEYWORDS Constructivism Epistemology Initial teacher education Professional development Professional studies Problem-based learning Teaching Viability INTRODUCTION In this paper I will describe an application of PBL in a different setting from those reported in the literature. The setting is a one-year post-graduate initial teacher education (ITE) program at the University of Sheffield, England. I will describe how and why PBL was introduced into this program. Outcomes will be presented both in terms of students’ evaluation of their experiences and in terms of assessment of students’ work. As well as particular issues arising 2 from this pilot use of PBL in ITE the question will be considered: is it possible to identify contextual conditions that are necessary for PBL to be viable in ITE? I will argue that the essence of what it is to be a teacher is inadequately described by an account of an individual practising alone in a classroom. Meanings, values, policies, beliefs – these are constructed in interpersonal exchanges in the community of teachers. At present, student teachers are left to learn how to make their way in this communal world – a world that is interpersonally and epistemologically open compared with the classroom. PBL may provide student teachers with a window into this world. BACKGROUND: ITE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD The majority of new teachers entering secondary schools in England do so via a specialist degree program followed by a one-year post-graduate certificate course in education, or PGCE. National requirements and standards for PGCE and other ITE programs have been specified by government (DfEE 1998). These are laid out in four domains: knowledge and understanding; planning, teaching and class management; monitoring, assessment, recording, reporting and accountability; and other professional requirements. PGCE student teachers spend a total of 12 weeks of their course in HE and 24 in schools. A widely adopted approach in the HE component of PGCE is to run two parallel strands, one focusing on issues that are subject specific and another, known in Sheffield University as Educational and Professional Studies or EPS, focusing on issues of relevance to all secondary school teachers. The core themes of the Sheffield EPS program are these: Reflecting on experience in Primary school Class management Equity and equality Pupil groupings Special educational needs Teaching and the law Current research and developments in pedagogy In addition, Personal, social and health education is a de facto core theme in EPS. The EPS program is well established in the School of Education at Sheffield University. There are indications that it is well regarded by other HEIs involved in ITE and by Ofsted, the government’s inspectorate. The students, despite a tendency to see themselves as subject specialists, consistently rate the overall EPS program favourably in end-of-course evaluation. THE CASE FOR INTRODUCING PBL INTO ITE 1. PBL models many elements of teachers’ professional practice. Many postgraduate ITE students are engaged on a brief journey from undergraduate life to the professional world of the practising teacher. PBL can provide them with what Bruner 3 called ‘scaffolding’ (Bruner, 1985), from the essentially individualistic nature of much of the work in further education and undergraduate studies towards the many collegial aspects of the working world of the teacher. For although the classroom remains the domain of the individual teacher, most other aspects of the teacher’s job are practised through the work of teams: departmental, pastoral, middle and senior management, policy, cross-curricular, special interest and so on. Using a PBL approach students learn to work alongside, with, and sometimes despite others. Issues may be explored in both breadth and depth by virtue of a team approach. Individuals are engaged not only with their own labours but also with the place of these labours in the broader context of a whole issue. As ITE teachers, our message to student teachers should be that it is professionally valuable for them to work collegially, in self-managed, task-oriented groups, and to learn to take initiative and responsibility as members of working groups. Let us model those things that we profess to value in our approach to educating our students: PBL provides an appropriate model. 2. A coherent epistemological framework A PBL approach is also capable of providing epistemological scaffolding from further education and undergraduate work towards the tasks, issues and problems encountered in teaching. College work presents students with tasks that tend to be characterised by an emphasis on factual knowledge and teacher-defined goals. The work is dominated from students’ perspectives by assessment considerations and this leads to the promotion of ‘surface’ learning rather than understanding (Ramsden 1992). Thinking shuts down when assessment objectives are met. Problematic issues in teaching tend to be anything but closed, however. If such issues are conceived in terms of goals, the goals themselves are liable to be contested; if they are conceived in terms of variables or parameters there are likely to be too many for a positivist approach to succeed. It may be more fruitful to conceive of problematic issues in teaching in terms of differences in values and beliefs than differences in factual truths. Not only the knowledge, therefore, but the nature of the knowledge with which people work when they are undergraduates is quite different from that occupying the thoughts of teachers working in professional teams. PBL in ITE bridges this divide, guiding students from the controlled epistemological environment of the undergraduate towards the open, often uncharted terrain of the teacher’s working world. In much undergraduate work, as well as in traditional approaches in ITE, students are required to reproduce coursework as individuals. Coursework tasks are set, defined and assessed by the HE institution. The prime objective of many students regarding their course is to pass it. They come to learn, if they have not already learnt from their prior schooling, that this can be achieved by the student matching as closely as possible her or his reading of the institution’s ideas of what counts as certifiable knowledge. Students readily come to view their own beliefs and understandings as secondary to this main goal. The PBL tutor, on the other hand, by relinquishing tight control over what will count as knowledge, begins to build an epistemological context that resembles that of the teacher’s working world. 4 Teaching is complex; it lacks an established theoretical underpinning; there are no agreed formulaic routes to success; issues are often highly contested. Somehow, though, teachers come to terms with this epistemological context. They do this by addressing significant issues of professional development in collegial groups, acknowledging the nature of the issues they face and aiming to learn what they can. The nature of knowledge in ITE is, of course, very similar to that in teacher professional development. PBL implicitly acknowledges this. In this way PBL in ITE is at one with its own content. Using PBL to explore big issues in teaching has the same reflexive coherence as, say, using a small group approach to explore small group teaching. PBL FROM A CONSTRUCTIVIST PERSPECTIVE Constructivism in its ‘radical’ form (Glasersfeld 1995) is a theory about knowing. It explores the question: what is it to know? Any discussion about learning, and in particular about PBL, has this issue embedded within it. Constructivism is not a method, though it contains profound implications for practice in education and other fields. Tobin and Tippins (1993) point out that it is helpful to regard constructivism as a referent for practical decision making. How then does PBL appear when referred to a constructivist framework? There are currently many variants of constructivism. The account in this paper owes much to Glasersfeld. Here I will only consider the aspects of constructivism that appear to me to connect most directly with PBL as a learning context. People use their knowledge to navigate their ways through everyday life. In this sense, a state of knowing, well captured, I think, by the colloquial English expression, ‘being in the know’, is an adaptation of the knower to her or his life-world. (More precisely, it is a mutual adaptation of the knower-knower’s life-world system.) Learning is a process of adjustment and extension to the current state of adaptation. Learning results in new states which grow, that is, they are constructed, from the current state. A new state persists if it is more viable, or better adapted to the learner’s experiential world. From this constructivist perspective there are two salient issues in discussing learning. The first is the person’s current state of knowing: learning starts from there. The second concerns the learner’s interactions with her or his environment. If learning is sought towards particular states of knowing, as in the case of teaching to a prescribed curriculum or working on a specified problem, then one of the options for the teacher is purposefully to manage the design of the learning environment. From the outset the PBL approach places great stress on learners’ current knowledge. If, in addition, a cyclical structure is employed in PBL, students keep returning explicitly to their updated current knowledge. However, mere possession of prior knowledge provides no guarantee about the learning that might take place. In a constructivist account, learning involves a connecting process between current knowledge and current experiences, and for useful learning to occur in some specific content domain, such as in a PBL problem, the learner must be able to connect, not with arbitrary prior knowledge but with knowledge that may have some useful bearing on the problem. Furthermore, this potentially useful prior knowledge must be currently accessible. Norman and Schmidt 5 describe this as a requirement that relevant prior knowledge must be activated. They argue that the PBL process helps to bring this about: ‘The instructional context must be such that activation can take place. Small-group discussion is one of the methods to activate relevant prior knowledge.’ (Norman and Schmidt, 1992). From a constructivist point of view it makes sense to think of the learning environment as design space, with the intention of making it as conducive as possible for learning in the intended field. It follows that PBL will be effective in an environment that is rich in possibilities for relevant experiences. A university or college that offers students ready and tooled-up access to library facilities including journals, multimedia, internet and other ICT facilities, and also people, is a highly suitable learning environment. PBL IN EPS: THE FIRST YEAR I introduced an outline of PBL to my new EPS tutor group of fourteen students at the start of the academic year 1999-2000. The students were offered the option of piloting PBL or following the same program as the other 160 students on the PGCE course. They took a group decision to pilot PBL. I formed three groups, all with mixed subject specialisms. The groups were introduced to three PBL problems that I had constructed. They negotiated which group would address which problem. The three problems were these: What do teachers do in order to manage their classes effectively? How can a teacher find out whether her/his teaching is successful? Should some children be segregated from mainstream schools? If so, on what basis; why is this beneficial and to whom is it beneficial? If not, what are the implications for mainstream schooling? The groups came to be known informally as CM (class management), TE (teaching effectiveness) and IS (integrate or segregate). The groups consisted respectively of four, five and five students. Their first PBL working session was in early October 1999. The project deadline was early January 2000. In this three month period there were eleven timetabled EPS meetings, each three hours long. Of this time I formally reserved approximately nine hours for self-managed PBL working. Groups also met by their own arrangement outside of scheduled times, although the structure of the PGCE course made this difficult as students were in schools for seven weeks and on vacation for a fortnight during this period. Indicators of outcomes of the PBL-EPS pilot 1. Interim presentations. Each group gave an interim presentation to myself and to the other groups, midway through the three month period. Peer feedback was given. I took an enquiring role (Scaife and Scaife, 2001), asking for clarification, asking about proposed further action, raising challenging questions and attempting to avoid overtly leading questions. 2. Final written report. Each group wrote a final report, with the assessment criteria being identical to those used for the EPS work of non-PBL students. This included an expected word count of between 6 two and four thousand words per student, which for groups with 5 members translated into an expectation of between ten and twenty thousand words. 3. Final presentation. Each group gave a final presentation to an audience of their peers, myself and an invited academic colleague. 4. Student evaluation Students formally evaluated their experiences of PBL in EPS in two ways: by anonymous questionnaire through verbal whole-group discussion in response to a semi-structured schedule of questions. The discussion took place between the fourteen students, myself and the colleague who attended the final presentations. Outcomes. 1. On-going. I carried out continuing diagnostic evaluation during the project period by observing and interacting with groups, and also through the interim group presentations. My interactions were low-key, taking the role of listener or curious enquirer. I observed students consistently engaged with group working and consistently focusing on the problem area. The groups maintained independent, self-managed working practice. There was, however, a cloud in what otherwise appeared to be a clear blue sky when one student raised the following concern privately to me: ‘If it seemed to be the case that not everyone was putting equal amounts of effort into this project, what could be done?’ 2. Final reports and presentations. The three written reports were assessed by myself as tutor, which is normal practice in the EPS course. They were also assessed independently by a colleague who was not a member of the EPS tutor team. Every report met the assessment criteria in full. It was evident that each group had invested considerable care, thought and effort into them. In a dozen years of teaching and assessing in EPS I have reached some views about what might be expected in the way of high quality work. Two of the three reports far exceeded my expectations. The final presentations bore out the impressions of engagement and effective researching. 3. Student evaluation. Fourteen completed questionnaires (100%) were returned. Students were asked 14 questions using a five-point rating scale, three open evaluative questions and five other questions. The following views emerged: Q2. Every student regarded their PBL problem as relevant (6) or highly relevant (8) in teaching. Q3. Students were asked how appropriate they regarded PBL as an approach to addressing their problem. The TE and IS groups regarded PBL as appropriate. The CM group was neutral overall. Q10. Eleven students approved, four strongly, of the self-managed approach to group working. The remaining three students were neutral. 7 Q7. All but three students favoured (6 strongly) mixed-specialism PBL groups. Q8. Questioned about the equitability of work-sharing in the groups four students (two each in CM and IS) expressed strong dissatisfaction. Q9. Only one student had reservations about any aspects of group working other than equitable work-sharing. Q15. Three students found the cyclical PBL structure unhelpful (1 very unhelpful) at the beginning of the project. Q16. Later in the project seven found the cyclical structure unhelpful (3 very). Several questions revealed a clear difference between the reported experiences of the CM group and those of the TE and IS groups. In every case, the CM group reported a lower satisfaction rating than the other groups. The questions were in the following areas: Q4. Relevance of the PBL approach in teaching Q5. Rating own learning from participation in PBL Q11. Level of the tutor’s involvement in group work Q17. Importance of PBL in the PGCE course Q18. View on whether PGCE should include PBL Q19. Expectation of using PBL in your own teaching. For questions 5, 17, 18 and 19 the CM group’s ratings were below neutral while the other groups’ ratings were above neutral. On question 11 every member of the TE and IS groups rated the level of the tutor’s involvement in group work as appropriate, whereas two of the four members of the CM group rated it as very insufficient. Students were asked which aspects of PBL they found particularly valuable (q.20). The dominant response, shared by nine people, was group working. Other aspects, raised by individuals, were the following: Incorporating the idea of being able to start again - so not feeling failures when a wrong approach was used Made use of own prior knowledge Researching a specific area PBL provides a structured and organised approach for tackling a large topic Very interesting problem (IS group member) Asked what changes students would recommend to help PBL become more valuable in ITE (q.21), the overwhelming issue raised was timing. They wanted additional time (typically two weeks) to work on the final report and presentation after the Christmas vacation. Two other matters were raised: A larger selection of problems should be offered Higher profile monitoring by the tutor of individuals’ contribution to group work. An invitation to make any other comments (q.22) evoked the following: Class management isn’t particularly suitable for PBL; it’s something you learn from experience The CM problem wasn’t solved ‘We had very different styles of working and writing – it is difficult to conduct intellectual research if you have to compromise’ 8 Many of the above points were repeated in the whole group evaluative discussion. These were some additional remarks that emerged: ‘We collaborated in planning but not in researching or writing.’ Group working gave momentum and impetus to the project. Feedback within the group was useful: ‘It’s a bit hard to do it wrong’ because of peer feedback. Class management isn’t ideal for PBL because group members tended to duplicate each others’ ideas. DISCUSSION It is evident from the evaluation data that the following issues figured highly in these students’ experiences of PBL: Timing, especially the position of the deadline for final reports Fairness in sharing workload Selection of PBL problem Concerns about timing were reported by members of all three groups. Dissatisfaction over the sharing of the workload was reported by members of both the CM and IS groups. The nature of the PBL problem was perceived to be a concern only to members of the CM group. It is clear from the evaluation data that members of CM experienced markedly less satisfaction in their PBL project than did the other students. An explanatory hypothesis is that this arose not from a single factor but from a combination of doubt about the appropriateness of their PBL problem and a sense of unfairness concerning workload distribution within the CM group. Amendments have been made to address these issues in the second PBL-EPS project, which is currently underway: The project period now extends from early October until late January, two weeks after the end of the vacation. The scheduled time for PBL groupwork has been increased to fourteen hours plus time for interim and final presentations. Three operating rules have been incorporated into the specifications for group working: 1. There must be a minuting secretary for every group meeting. This role can rotate if the group chooses. 2. Minutes from group meetings must be included in the final report as an appendix. 3. The workload in the group should be periodically reviewed. Each member of the group is responsible for helping to maintain a fair distribution of workload. In order to respond to the students’ need to perceive their PBL problem as suitable and appropriate, the three groups in the second year chose their PBL problems from a list of ten. The three chosen were these: Fair education? How fair is education? Are children treated fairly in school? Do schools treat boys and girls equitably? High and low attainers? Children from majority and minority ethnic groups? What are the experiences of the pupils themselves? 9 Good group, bad group Set, stream, band or mix children – how should they be grouped into classes? Given such diversity of practice nationwide, is any method of grouping as good or bad as any other? Boys’ own classes? Girls’ only groups? Is there a case for single-sex classes in mixed schools? Whose views matter? What are the important criteria? In the evaluative comments, two students referred to their work as research (questions 20 and 22). In my experience this is an unusual - and welcome - departure from the expression students normally use to describe their conception of EPS coursework, namely ‘doing the assignment’. It may not be an overstatement to suggest that this could be indicative of an attitudinal shift, away from anti-intellectualism and towards a sense of ownership. A number of unresolved issues emerged from the pilot: 1. I did not anticipate that students would find the cyclical structure unhelpful. It appeared as if they had abandoned it fairly quickly in their group working. In view of question 9 this does not seem to have been a matter of dysfunctional group processes. The cyclical structure was unfamiliar to most people and it may have been that they did not perceive a need for it. I have taken the somewhat coercive step of placing it explicitly on the agenda for group meetings in the current PBL projects. It will emerge from evaluation at the end of the project what impact this forced engagement has. 2. One student remarked (q.22) that the PBL problem had not been solved. It is quite likely that the student had a background in science, which led to a particular expectation of what constitutes a proper problem. Is there a need to address this, prior to students embarking on PBL? To put this another way, is it helpful for students to learn in advance about distinct research paradigms or is this better left to emerge during PBL? 3. Is it realistic – and is it ethical – to expect groups to manage their own workload distribution? Connected questions are whether, and how, to intervene in issues involving group working processes? 4. How can we persuade students to think about learning when they know their work will be graded? I have taken a leaf from Postman and Weingartner (1969) in this respect, in an attempt to downplay students’ consciousness of grading. I have put it to them that by doing PBL they will compile a report that demonstrates to prospective employers both their special expertise in the researched issue and their first-hand experience of an innovative learning context. Secondly, they will be in possession of knowledge that will make them unusually expert in their researched field amongst their peers. Thirdly they will be in a position to educate their colleagues both in HE and in schools, contributing to professional development in teaching. And finally – and by the way – they will provide sufficient evidence to warrant an official pass grade on their course. 10 5. What conditions are needed in order for PBL to be viable in ITE? There were several contributory factors leading to the decision to pilot PBL in the EPS program at Sheffield University: Relative lack of curriculum content. The core of the EPS program is compact enough to accommodate a focus on learning for understanding. A flexible timetable containing a number of floating sessions. Use of these sessions is decided by negotiation between tutors and students. The place of EPS in the School of Education. EPS is regarded as a successful course in terms of both student learning and student evaluation. It is also seen, however, as demanding in terms of staff time. The consequence is that it occupies a somewhat stable position on the margins of the School’s work. Perhaps as a result of this position EPS has had a history of ‘openness’ to innovation. There is a strong interest among tutors in learning and in a student-focused approach to teaching. On the basis of the reported pilot it appears that these conditions may be sufficient for PBL to be viable in ITE. The question remains whether the conditions are also necessary, in the sense that without them, PBL in ITE would not succeed. References Bruner J (1985), Vygotsky: a historical and conceptual perspective. In Wertsch J (ed.) Culture, Communication and Cognition: Vygotskian Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Department for Education and Employment (1998) Teaching: High Status, High Standards (Circular 4/98). London: DfEE Glasersfeld, E von (1995) Radical Constructivism. London: Falmer. Norman G R and Schmidt, H G (1992) The Psychological Basis of Problem-based Learning: A Review of the Evidence. Academic Medicine 67, 9, 557-565 Postman N and Weingartner C (1969) Teaching as a Subversive Activity. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Ramsden P (1992) Learning to Teach in Higher Education. London: Routledge. Scaife J A and Scaife J M (2001) Supervision and Learning. In Scaife J M, Supervision in the Mental Health Professions. London : Routledge. (In press) Tobin K and Tippins D (1993) Constructivism as a referent for teaching and learning. In Tobin K (ed.) (1993), The Practice of Constructivist in Science Education. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.