Chapter 11: Monopoly Prepared by: Kevin Richter, Douglas College

Chapter 11:

Monopoly

Prepared by:

Kevin Richter, Douglas College

Charlene Richter,

British Columbia Institute of Technology

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

1

Introduction

Monopoly is a market structure in which a single firm makes up the entire market.

Monopolies exist because of barriers to entry into a market that prevent competition.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

2

Introduction

Legal barriers , such as patents, prevent others from entering the market.

Sociological barriers – entry is prevented by custom or tradition.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

3

Introduction

Natural barriers – the firm has a unique ability to produce what other firms can’t duplicate.

Technological barriers – the size of the market can support only one firm.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

4

Differences Between a Monopolist and a Perfect Competitor

A competitive firm is too small to affect the price.

The monopolist takes into account the fact that its production decision can affect price.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

5

Differences Between a Monopolist and a Perfect Competitor

A competitive firm's marginal revenue is the market price.

A monopolistic firm’s marginal revenue is not its price – it takes into account that in order to sell more it has to decrease the price of its product.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

6

Differences Between a Monopolist and a Perfect Competitor

Monopolist as the only supplier faces the entire market demand curve.

Therefore, monopoly demand is downward sloping, and to increase output the firm must decrease its price.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

7

Model of Monopoly

How much should the monopolistic firm choose to produce if it wants to maximize profit?

The monopolist employs a two-step profit maximizing process; it chooses quantity and price.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

8

Monopolist’s Price and Output

Numerically

The first thing to remember is that marginal revenue is the change in total revenue that occurs as a firm changes its output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

9

Monopolist’s Price and Output

Numerically

When a monopolist increases output, it lowers the price on all previous units.

As a result, a monopolist’s marginal revenue is always below its price.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

10

Monopolist’s Price and Output

Numerically

In order to maximize profit, a monopolist produces the output level at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue.

Producing at an output level where MR >

MC or where MR < MC will yield lower profits.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

11

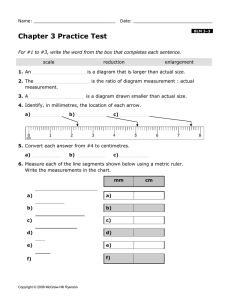

Profit Maximization for a Monopolist

Output Price TR

2

3

0

1

4

5

8

9

6

7

36

33

30

27

24

21

18

15

12

9

0

33

60

81

96

105

108

105

96

81

MR

—

33

27

21

15

9

3

–3

–9

–15

TC

47

48

50

54

62

78

102

142

196

278

MC

—

1

2

4

8

16

24

40

56

80

ATC Profit

48.00 –15

25.00

18.00

15.50

15.60

17.00

–47

10

27

34

27

6

20.29 –37

24.75 –102

30.89 –197

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

12

Monopolist’s Price and Output

Graphically

The marginal revenue curve is a graphical measure of the change in revenue that occurs in response to a change in price.

It tells us the additional revenue the firm will get from an additional unit of output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

13

MR = MC Determines the Profit-

Maximizing Output

If MR > MC , the monopolist gains profit by increasing output.

If MR < MC , the monopolist gains profit by decreasing output.

If MC = MR , the monopolist is maximizing profit.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

14

Price a Monopolist Charges

The MR = MC condition determines the quantity a monopolist produces.

The monopolist will charge the maximum price consumers are willing to pay for that quantity.

That price is found on the demand curve.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

15

Price a Monopolist Charges

To determine the profit-maximizing price

(where MC = MR), first find the profit maximizing output.

That quantity determines the price the monopolist will charge.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

16

Determine Monopoly Price and Output

Price

$36

30

24

18

12

6

0

6

12

Monopolist price

MC

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

MR

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

17

Comparing Monopoly and Perfect

Competition

Equilibrium output for both the monopolist and the competitor is determined by the MC

= MR condition.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

18

Comparing Monopoly and Perfect

Competition

Because the monopolist’s marginal revenue is below its price, price and quantity will not be the same as it is under perfect competition.

The monopolist’s equilibrium output is less than, and its price is higher than, for a firm in a competitive market.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

19

Comparing Monopoly and Perfect

Competition

MC

Price

$36

30

24

18

12

6

0

6

12

Monopolist price

Competitive price

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

MR

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

20

Profits and Monopoly

Draw the firm's marginal revenue curve.

Determine the output the monopolist will produce by the intersection of the MC and

MR curves.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

21

Find Monopoly Price and Output

Price

MC

D

MR

Quantity

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

22

Profits and Monopoly

Determine the price the monopolist will charge for that output.

Determine the average cost at that level of output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

23

Find Monopoly Price and Output

Price

MC

P

M

MR

Q

M

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Quantity

24

Profits and Monopoly

Determine the monopolist's profit (loss) by subtracting average total cost from average revenue ( P ) at that level of output and multiply by the chosen output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

25

Profits and Monopoly

The monopolist will make a profit if price exceeds average total cost.

The monopolist will make a normal return if price equal average total cost.

The monopolist will incur a loss if price is less than average total cost.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

26

Monopolist Making a Profit

A monopolist can make a profit.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

27

Monopolist Making a Profit

Price

MC

0

ATC

P

M

C

M

Profit

A

B

MR

Q

M

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Quantity

28

Monopolist Breaking Even

A monopolist can break even.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

29

Monopolist Breaking Even

Price

P

M

MC

ATC

0

MR

Q

M

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Quantity

30

Monopolist Making a Loss

A monopolist can make a loss.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

31

Monopolist Making a Loss

Price

C

M

P

M

Loss

B

A

MC

ATC

0

MR

Q

M

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Quantity

32

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

People’s purchase decisions don’t reflect the true cost to society because monopolies charge a price higher than marginal cost.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

33

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

The marginal cost of increasing output is lower than the marginal benefit of increasing output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

34

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

A single price monopoly creates welfare losses.

Welfare losses can be illustrated by the area of consumer and producer surplus that is lost due to smaller output produced, compared to output produced in perfect competition.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

35

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

Compare the normal monopolist's equilibrium to the equilibrium of a perfect competitor.

Equilibrium in both market structures is determined by the MC = MR condition.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

36

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

But the monopolist's MR is below its price, thus its equilibrium output is different from a competitive market.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

37

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

The welfare loss of a monopolist is represented by the triangles B and D .

The welfare loss is often called the deadweight loss or welfare loss triangle .

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

38

Welfare Loss from Monopoly

Price

MC

P

M

P

C

0

C

D

B

A

MR

Q

M

Q

C

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Quantity

39

Price-Discriminating Monopolist

Price discrimination is the ability to charge different prices to different individuals or groups of individuals.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

40

Price-Discriminating Monopolist

In order to price discriminate, a monopolist must be able to:

Identify groups of customers who have different elasticities of demand;

Separate them in some way; and

Limit their ability to resell its product between groups.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

41

Price-Discriminating Monopolist

A price-discriminating monopolist can increase both output and profit.

It can charge customers with more inelastic demands a higher price.

It can charge customers with more elastic demands a lower price.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

42

Price Discrimination Occurs in the

Real World

Movie theaters give senior citizens and child discounts.

Airline seat sales usually require Saturday night stopovers.

Automobiles are seldom sold at their sticker price.

Theaters have midweek special rates.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

43

Price-Discriminating Monopolist

A perfect price discriminating monopoly will stop expanding its output when MR = MC, which corresponds to the perfectly competitive output.

The deadweight loss is therefore eliminated under perfect price discrimination.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

44

Perfect Price Discrimination

Price

4

3

6

5

10

9

8

7

2

1

MC

D=MR

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

MR

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All

Quantity (number of consumers) rights reserved.

45

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

What prevents other firms from entering the monopolist’s market in response to profits the monopolist earns?

Monopolies exist because of barriers to entry .

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

46

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Barrier to entry – a social, political, or economic impediment that prevents firms from entering the market.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

47

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

In the absence of barriers to entry, the monopoly would face competition from other firms, which would erode its monopoly position .

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

48

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Economies of scale:

When production is characterized by increasing returns to scale, the larger the firm becomes, the lower its per unit costs become.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

49

Economies of Scale

If significant economies of scale are possible, it is inefficient to have two producers.

If each produced half of the output, neither could take advantage of economies of scale.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

50

Economies of Scale

A natural monopoly is an industry in which one firm can produce at a lower cost than can two or more firms.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

51

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Economies of scale:

In cases of natural monopoly, technology is such that minimum efficient scale is so large that average total costs decrease over the range of potential output.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

52

Natural Monopoly

C

3

C

2

C

1

0

ATC

Q

⅓

Q

½

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

Q

1

Quantity

53

Economies of Scale

There is no welfare loss in the natural monopoly situation.

There can actually be a welfare gain because a single firm is so much more efficient than several firms producing the good.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

54

Natural Monopoly

P

M

C

M

Profit

C

C

P

C

0

Loss

MR

Q

M

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

Q

C

ATC

MC

D

Quantity

55

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Set-up costs:

In many industries high set-up costs characterize production.

The industry may be highly capital-intensive, requiring a large investment in expensive but highly specialized capital.

Examples are an oil refinery or a diamond mine.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

56

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Set-up costs:

In some industries a lot of money may be spent on advertising.

Heavy advertising creates a barrier to entry in those cases, such as in the perfume industry or the automobile industry.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

57

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Legislation:

Monopolies can also exist as a result of government charter.

Patents are another way in which government can grant a company a monopoly.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

58

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Legislation:

A patent is a legal protection of technical innovation that gives the inventor a monopoly on using the invention.

To encourage research and development of new products, government gives out patents for a wide variety of innovations.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

59

Barriers to Entry and Monopoly

Other barriers to entry:

Sometimes one company can gain ownership of some essential aspect of the production process, a unique input, or control over a resource.

An example is DeBeers. By controlling the worldwide distribution network for diamonds, the company enjoys a monopoly in the diamond industry.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

60

Normative Views of Monopoly

The public generally views monopolies the way the Classical economists did – they consider them unfair and wrong.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

61

Normative Views of Monopoly

Some normative arguments against monopoly include:

Income distributional effects associated with monopoly.

Rent-seeking activities in which people spend resources to lobby government for the monopoly power.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

62

Normative Views of Monopoly

The public does not like the distributional effects of monopoly.

They believe that it transfers income from

“deserving” consumers to “undeserving” monopolists.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

63

Normative Views of Monopoly

It is possible for the well-financed and the well-connected to garner government favours.

The public prefers that firms do productive things rather than lobby for government favours.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

64

Government Policy and Monopoly:

AIDS Drugs

The patents for AIDS drugs are owned by a small group of pharmaceutical companies.

They can charge a very high price for a drug whose marginal cost is very low.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

65

Government Policy and Monopoly:

AIDS Drugs

What, if anything, should the government do?

Government could force the producer to charge a price equal to its marginal cost.

Society would be better off but this would create a significant disincentive for drug companies to do further research on other life-threatening diseases.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

66

Government Policy and Monopoly:

AIDS Drugs

Another alternative is for the government to buy the patents and allow anyone to produce the drugs.

Payment would come from increased taxes and would be quite expensive.

The cost of regulation would decrease, but it would raise the question as to which patents the government should buy.

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

67

Monopoly

End of Chapter 11

© 2006 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

68