INTERGENERATIONAL ENRICHING EXPERIENCES: A SURVEY OF HELPING PROFESSIONALS A Thesis

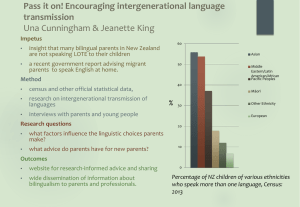

advertisement