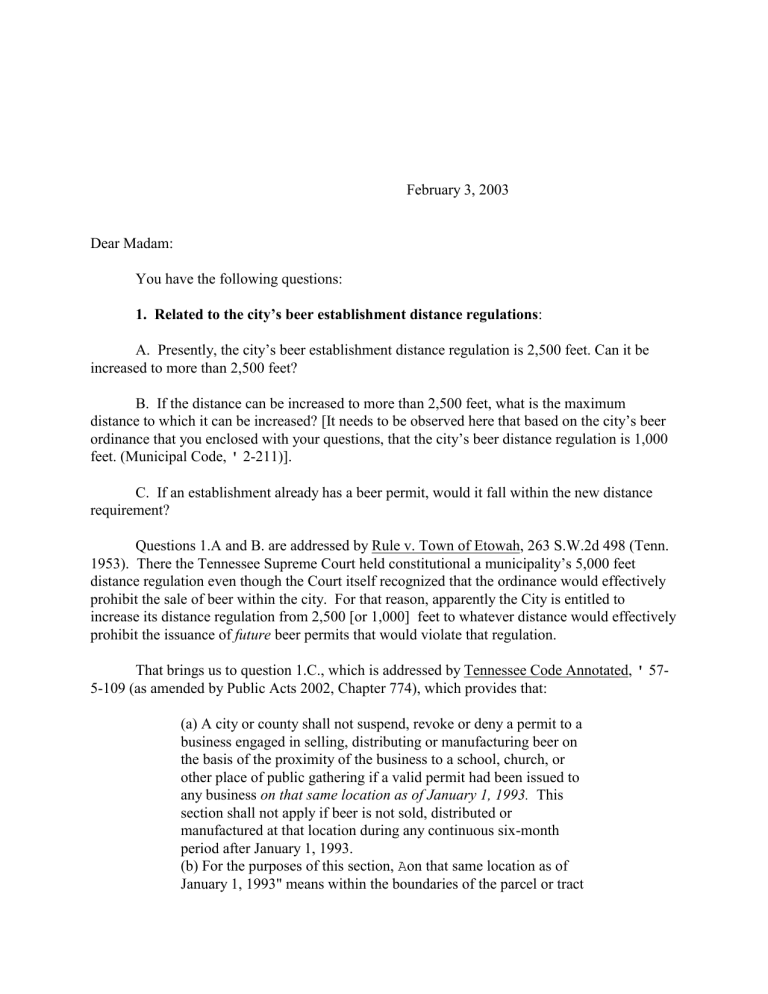

February 3, 2003 Dear Madam: You have the following questions:

February 3, 2003

Dear Madam:

You have the following questions:

1. Related to the city’s beer establishment distance regulations :

A. Presently, the city’s beer establishment distance regulation is 2,500 feet. Can it be increased to more than 2,500 feet?

B. If the distance can be increased to more than 2,500 feet, what is the maximum distance to which it can be increased? [It needs to be observed here that based on the city’s beer ordinance that you enclosed with your questions, that the city’s beer distance regulation is 1,000 feet. (Municipal Code, ' 2-211)].

C. If an establishment already has a beer permit, would it fall within the new distance requirement?

Questions 1.A and B. are addressed by Rule v. Town of Etowah, 263 S.W.2d 498 (Tenn.

1953). There the Tennessee Supreme Court held constitutional a municipality’s 5,000 feet distance regulation even though the Court itself recognized that the ordinance would effectively prohibit the sale of beer within the city. For that reason, apparently the City is entitled to increase its distance regulation from 2,500 [or 1,000] feet to whatever distance would effectively prohibit the issuance of future beer permits that would violate that regulation.

That brings us to question 1.C., which is addressed by Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 57-

5-109 (as amended by Public Acts 2002, Chapter 774), which provides that:

(a) A city or county shall not suspend, revoke or deny a permit to a business engaged in selling, distributing or manufacturing beer on the basis of the proximity of the business to a school, church, or other place of public gathering if a valid permit had been issued to any business on that same location as of January 1, 1993.

This section shall not apply if beer is not sold, distributed or manufactured at that location during any continuous six-month period after January 1, 1993.

(b) For the purposes of this section, A on that same location as of

January 1, 1993" means within the boundaries of the parcel or tract

February 3, 2003

Page 2 of the real property on which the business was located as of

January 1, 1993. The provisions of this section apply whether or not the business was a conforming or nonconforming use at the time of the move.

(c) If a business applies for a beer permit within the continuous sixmonth period referenced in this section, and if the city or county denies the business a permit and if the business appeals that denial, a new six-month continuous sale period shall begin to run on the date when the appeal of that denial is final.

That statute “grandfathers” beer establishments that would otherwise violate distance regulations as of January 1, 1993. But I note that under ' 2-211 of the Municipal Code, the city appears to have grandfathered all beer establishments that had a valid permit as of September 4,

2001! As far as I can determine, the city is probably bound by its extension of the grandfather period.

2. Related to the issuance of future beer permits:

A. Can the city stop issuing beer permits (there are presently nine outstanding permits)?

B. If the board decides to stop issuing permits, can it legally revoke all the present outstanding permits?

With respect to Question 2.A., presently, the Municipal Code, ' 2-208(b) [as amended by

Ordinance No. 693] provides for not more than 2 on premises permits, not more than 6 off premises permits, and not more than 2 on/off premises permits, provided that when the population of the city increases by 1,000 over the 2000 census, one additional permit shall be issued. [It is not clear in the ordinance whether the increase in permits applies to each class of permits.] DeCaro v. City of Collierville, 373 S.W.2d 466 (Tenn. 1963), and State ex rel.

AmvetsPost 27 v. Beer Board, 717 S.W.2d 878 (Tenn. 1986), Watkins v. Naifeh, 635 S.W.2d

104 (Tenn. 1982), and other cases, stand for the proposition that a municipality has virtually unlimited discretion with respect to the number of both on and off premises permits. But the limitation on the number of beer permits, of course, must be reflected in the city’s beer ordinances. [See Brooks v. Garner, 566 S.W.2d 531 (Tenn. 1966). Also see Harper Enterprises v. City of Bean Station, slip copy, Tenn. Ct. App. 2002]

With respect to Question 2.B., it has been held that a municipality in Tennessee has the authority to entirely prohibit the sale of beer. [Howard v. Christmas, 176 S.W.2d 821 (1944);

Thompson v. City of Harriman, 568 S.W.2d 92 (Tenn. 1978); Goldston v. City of Harriman, 565

S.W.2d 858 (Tenn. 1978); Gatlinburg Beer Regulation Committee v. Ogle, 206 S.W.2d (1947);

February 3, 2003

Page 3

Ketner v. Clabo, 225 S.W.2d 54 (1949).] But the question of whether a municipality can revoke all beer permits that have previously been legally issued to attain a policy of entirely prohibiting the sale of beer in the municipality was last answered by Grubb v. Mayor and Aldermen of

Morristown, 203 S.W.2d 593 (1947). There the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld the revocation of 18 outstanding beer permits legally issued by the city when the city apparently passed an ordinance entirely prohibiting the sale of beer within the city. After citing a number of cases holding that no one had a right to a beer permit, the Court reasoned that:

All of the foregoing cases as well as others which might be cited are conclusive of the question that, since the business of selling beer is subject to unlimited restrictions, it cannot be said that such restrictions, even to the extent of a prohibition, are “unreasonably oppressive, discriminatory,” and violate any civil right of the complainants....[At 595]

But Grubb is a 1947 case; I am not sure that a similar case would stand up today against equitable challenges. The truth is that I do not know which direction the courts would go if directly confronted with that question. If your City attempts to carry out that policy, it will be the guinea pig on that issue.

The barrier frequently cited for the proposition that a city cannot revoke such permits to carry out such a policy is Sparks v. Beer Committee of Blount County, 339 S.W.2d. 23 (Tenn.

1960). In that case, Sparks was issued a beer permit in 1951. In 1958 a church was established within the 2,000 prohibited feet that applied to county beer permits. In 1959 the Blount County

Beer Board revoked Sparks’ permit on the sole ground that his beer establishment was within

2,000 feet of a church. The Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the revocation of Sparks’ permit, reasoning that while the county had the legal right to revoke the permit, the revocation was not equitable in that case. Presumably, Sparks applies to all beer establishments that hold a valid permit where a school, church or other place of public gathering locates within the prohibited distance.

Tennessee Attorney General’s Opinion dated February 17, 1981, distinguishes Sparks in concluding that the City of Hendersonville could entirely prohibit the sale of beer after having allowed it for a number of years. Sparks dealt with a county beer board, and “counties have never had the power to regulate the sale of beer to the point of prohibition.” In addition, reasoned the Tennessee Attorney General, in Sparks, the sale of beer was still a lawful business, and the facts involved the arbitrary and capricious deprivation by the county beer board of one individual’s right to pursue a lawful business for which he had a license. That opinion suggests that the City of Hendersonville could adopt a plan providing for the attrition of beer businesses in the city, but was not required to do so.

February 3, 2003

Page 4

Tennessee Attorney General Opinions No. 39, October 17, 1975 and 84-180, June 14,

1984, opine that persons holding valid county beer permits are entitled to continue operation when they are annexed into a municipality that does not permit beer sales. Those opinions appear to be in line with the logic of Sparks and Needham, below. In Thompson v. City of

Harriman, 568 S.W.2d 92 (Tenn. 1978), the Court itself pointed out that counties and cities were different in the sense that cities could entirely prohibit the sale of beer while counties could not.

The Court went on to uphold the city’s action in refusing to recognize a beer permit issued by the county in territory annexed by the city after the annexation. The city, observed the Court, entirely prohibited the sale of beer and had never issued a beer permit. It is reasonable to wonder whether the Court would have reached the same result if the city had issued beer permits, then revoked them to entirely prohibit the sale of beer.

The reason to wonder increases with Needham v. Beer Board of Blount County, 647

S.W.2d 226 (1983). There the Court considered the question of whether the county could revoke a beer permit that it issued in violation of its 2,000 feet distance rule: The Court had a legal right to revoke the beer permits, declared the Court:

We hold that a beer board can revoke such a permit. A A license to sell liquor [or beer] is not a contract by right of property but is merely a temporary permit to do that which would otherwise be unlawful. [Citations omitted.] There is no property right in a permit to sell beer. [Citing Sparks, above.]

In this case, the Blount County Beer Board had the right to revoke

Plaintiff’s permits and in revoking the discriminatorily issued permits, restored the 2,000 rule for Blount County. [At 230]

But the Court, in an exercise of its equitable powers, declared that the permits at issue could not be revoked because “Plaintiffs, Needham and Humphreys relied on the license to their detriment and we are of the opinion that the revocation of their licenses would create a significant hardship and would be unjust.” [At 231] The permits in this case, continued the

Court, “were not issued through misrepresentation by the Plaintiffs, but by mutual mistake as to how the distances should be properly measured.” [At 231] If Needham’s and Humphrey’s beer establishments had been in the city, and had they held city permits, and had the city made a mistake as to the method of measurement, Sparks would have undoubtedly applied in that case.

In what respect would the equities differ if a city revoked a beer permit on the basis of a mistaken method of measurement, and pursuant to a policy to entirely prohibit the sale of beer?

Neece v. City of Johnson City, 767 S.W.2d 638 (Tenn.1989), appears to confuse the question of whether equity will even intervene in the case of persons who held county beer

February 3, 2003

Page 5 permits at the time of the annexation of their establishments into the city. There the city had a limit of 21 off-premise permits, all of which had been issued. But the city created a new class of permit holders consisting of county beer permit holders annexed into the city. The new class of permit holders could continue to sell beer inside the annexed areas, but could not transfer their permits to locations within the “old” city limits, as could the 21 city beer permit holders. The

Court rejected his claim that the non-transferability provision was a violation of due process and equal protection, adopting the reasoning of the trial court, which was that:

As concerns operation within the city’s boundaries, the maximum of twenty-one (21) off-premises licenses was reached prior to the annexation of Neece’s property. Thus at the time he [Neece] could only hope to purchase an existing license if he wanted to operate within the city . He still has that opportunity if one of the preexisting twenty-one licenseholders wishes to sell to him.

Additionally, by virtue of the annexation, he now has on offpremises beer establishment in the City, the license to which he may convey to a qualified person. He simply cannot change the location of that establishment’s license to another location within the City’s boundaries, but he did not have that right prior to the annexation. So Neece has lost nothing.... [Emphasis is mine.]

It is difficult to determine what the Court meant when it said, “Thus at the time he could only hope to purchase an existing license if he wanted to operate within the city....” Certainly it arguably means that had the city not authorized the new class of permit holders those persons who held county permits at the time of annexation would simply not have had the right to sell beer anywhere in the city, even in the annexed part. If that is true, the equitable considerations at work in Sparks and Needham would not have helped them.

In Goldston v. City of Harriman, 565 S.W.2d 858 (Tenn. 1978), the Court made some noises indicating that Sparks would apply to persons holding county permits at the time of annexation. There the city and county beer permits holders in territory annexed by the city entered into an agreement under which the permit holders that had been issued beer permits by

Roane County could continue to sell beer in the city, and the Roane County Beer Board would deal with the continuation and revocation of such permits. The parties expressly recognized in the agreement that Sparks might apply to prevent the city from taking their beer permits. Roane

County subsequently issued a beer permit to a new business in the annexed territory, which the city refused to recognize. The Court held that the Roane County beer permits issued for the new establishment were not valid. However, the case also mentions a subsequent annexation took in territory in which there was a Holiday Inn that also held a beer permit issued by Roane County.

Without protest the city allowed the Holiday Inn to continue selling beer. In what appears to be

February 3, 2003

Page 6 dicta, the Court says of the Roane County beer permit issued to the Holiday Inn:

Neither does the conduct of the City recognizing the continued validity of the Holiday Inn beer permit which had been issued by the Roane County Beer Board prior to annexation of the location in

1966 furnish an aid to the defendant. We do not find it necessary to decide whether the City was bound to recognize the continuing validity of the Holiday Inn permit after the 1966 annexation became effective, see Sparks v. Beer Committee of Blount County,

207 Tenn. 312, 339 S.W.2d 23 (1960); suffice it to say that we are of the opinion that to recognize the continued validity of such a permit under the circumstances would not be an arbitrary or unreasonable action. [At 861] [Emphasis is mine.]

It seems to me the Court, albeit apparently in dicta, came close to saying that Sparks would have applied to the Holiday Inn’s beer permit. True, it had been issued by Roane County, but the city had recognized it. If the validity of the Holiday Inn’s permit rested upon its legal issuance by Roane County and its recognition by the City of Harriman, it is difficult to see why the same equitable considerations that went into Sparks and Needham would not apply to permits issued by the city and subsequently revoked by the city in furtherance of a policy adopted to prohibit the sale of beer. It would be easy for a court to conclude that while a city has the legal right to revoke beer permits in the pursuit of such policy, it cannot equitably revoke them.

The argument that for equitable purposes there is a distinction between the holders of legallyissued county beer permits at the time of annexation, and the holders of legally-issued city beer permits on the ground that city’s have the authority to entirely prohibit the sale of beer while counties do not, may be a tough one to make.

3. Number of beer permits

I addressed this question in the answer to question 1.

Sincerely,

Sidney D. Hemsley

Senior Law Consultant

SDH/