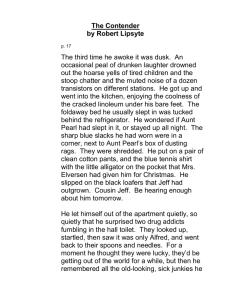

1 People ask me about the time I mashed a gun... I’ll just start there. I remembered everything he taught me.

advertisement