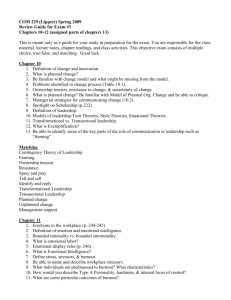

Document 16086962

advertisement