HIGHER EDUCATION AS A PEER SUPPORT INTERVENTION A Project

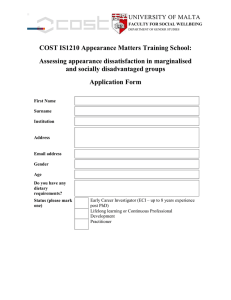

advertisement