Communicative Interactions

Communicative Interactions

1936

Personal Goals in conversation

?

State an opinion

find information

get something

exert power

Social goals

avoid conflict

make friends

How do we win friends and influence people through our conversation?

We have to be

Agreeable

appease people

Be polite

Rules of Talk

Rules of talk determine:

Who talks and when they talk (turn taking)

Who sets the topic of the talk

Who may change the topic and when it may be changed

What kind of language is used in the talk (formal, informal, polite)

Structural properties of conversations

conversation is based on principles of turn taking

We use everyday when we carry on conversations in every imaginable social context

• taking turns,

• waiting for turns,

• competing for turns,

• talking out of turn,

• talking so no one can get a “word in edgewise" and so on.

Turns are the key to modeling how conversation works, how conversation is organized.

the basic structure of turns, their allocation are context free

but the ways that turns are used by speakers, their length and content, are sensitive to situation, allowing greater or lesser opportunities of coparticipants

So we have to look at both the structure of turn taking and the uses that people make of them

Turn-taking

Turn-taking is the fundamental organization of social interaction.

Turn transition points are places in conversation when speaker change may or does occur.

Turn transition points bound the fundamental conversational unit, the turn.

Thus, a turn is a point in ones talk when another may or does speak

In any language, there are rules for conversation that govern such things as how to interrupt a speaker, how to know when a speaker’s turn is over, how to change a topic, what topic is appropriate, etc.

Turn Allocational Component

how turns are allocated among participants in a conversation

three options

1. Current Speaker selects Next Speaker

2. Next Speaker Self-selects as Next

3. Current Speaker Continues.

occurrences of more than one speaker at a time are common but brief

transitions from one turn to the next with no gap and no overlap or with slight gap or overlap make up the majority of transitions

speakers give us clues about when they are finished speaking or when they expect us to speak or not to speak.

These clues are known as discourse markers.

Criteria for recognizing these points in a conversation are:

1. Pauses - A pause as short as 0.3 seconds is time enough for a person to take a turn in a conversation.

2. In-breath

3. sentence intonation - points in a conversation when a speaker's voice marks the end of a sentence.

4. Question intonation - points in the conversation when a speaker's voice marks the end of a question.

5. Speaker change

The next speaker normally begins his or her turn at the completion of a turn allocation unit turn taking conversation

In multiparty conversations turns to not rotate in a fixed sequence but are variable in distribution

Turns allocated in two ways

Current speaker selection and self- selection

Order of turns (in multiparty conversations), size of turn, and length of conversation vary

The features are sensitive to social constraints based on relative status of participants

Generally, in encounters between unequal’s, higher status members assume more rights to turns and to longer turns than do those of lower status

Adjacency Pair

a pair of conversational turns by two different speakers such that the production of the first turn (called a first-pair part) makes a response (a second-pair part) of a particular kind relevant.

i.e. utterances are linked automatically to particular kinds of responses

For example, a question, such as "what's your name?", requires the addressee to provide an answer in the next conversational turn.

In multiparty conversations they are a means by which the current speaker

selects the next

A failure to give an immediate response is noticeable and accountable.

Many actions in conversation are accomplished through adjacency pair sequences, for example:

offer-acceptance/rejection

greeting-greeting

complaint-excuse/remedy

request-acceptance/denial

Talk tends to occur in responsive pairs adjacency pairs etc

Tag questions

Utterances beginning with a declarative proposition to which a question or “tag” added

particularly effective for ending a turn because the addressee is obliged by confirming or denying the tag.

If current speaker does not select next speaker, a next speaker may “self-select”.

But the next speaker may not just start talking anytime he or she wants to?

there are special “places” in the talk that speaker-changes or “speaker transitions” become relevant?

turn entry devices

devices that signal a person’s desire

Beginners begin with a beginning with words such as “well”,

“but” “and” or “so

because of things like overlaps we have repair mechanisms to correct errors so that one party in simultaneous talk stops and allows the other to complete her turn

social norms based on status affect actual outcomes

higher status people tend to interrupt or complete their turns when interrupted

lower status people are apt to be successfully interrupted.

If no other participant selects him or herself as next speaker, current speaker may, but need not, continue speaking, for example:

A: Great weather today!

(.)

A: Wanna play tennis later?

Devices to maintain the floor

• Increase volume

• “hold that thought”

• “um” and “ahs”

backchannel cues

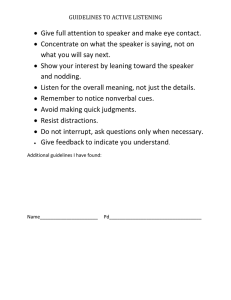

When one person is speaking to another, the listener has to let the speaker know that they are listening and want the speaker to continue.

This is done differently in different languages, but most languages use come kind of speech device to signal the speaker to continue. These devices are know as backchannel cues.

In English, the listener often says uh hu, ya, right, sure, yes or simply nods the head once in a while.

These devices have no referential meaning.

Saying yes is an acknowledgement of what is said not agreement with it

Their purpose is to maintain the interaction by indicating one’s attention to and ratification of the speaker’s talk

They must be well timed to clauses and phrases within the speaker’s turn

Too many vocalizations by listeners may be seen as disruptive and too few as showing a lack of interest

If you don’t believe these are necessary for conversation in English, try an experiment. Next time you are speaking to someone don’t do anything when it’s their turn to talk and see what happens.

Greetings

Conversations have beginnings and ends that frame the activity of talk

typically begin with some sort of greeting

end with some form of closing

Greetings and closings are examples of adjacency pairs

Greetings are routines that mark a person’s availability to talk

Both participants signal by their response that they understand and agree to a jointly negotiated behaviour including their willingness to engage in talk

"

Good Morning/Afternoon/Evening. It is nice to meet you."

Long time no see

after an initial greeting people propose and ratify topics of conversation

people of higher status assume more rights to speak

Generally, people are more interested to talk about themselves.

Often the conversation on the situation – the weather

Termination of encounters

usually achieved through a process at the end of a topic

e.g. well, or so, or okay or fine – words of agreement

another technique is to return to a prior topic

• Oh, look at the ______ . I'll have to go.

• It's been ______ talking to you.

• We have to make ______ to get together some

• Let's do ______ some time.

• I won't ______ you any longer.

• I'll ______ you go now.

• I'm going to have to ______ .

• I'll have to say goodbye.

• Let's continue this another ______ . _

• _____ care.

• Nice meeting ______ .

• Let's get ______ soon.

Cohesiveness in conversations

The links that hold a conversation together

Conversations are internally cohesive because of their formal structure and because techniques that speakers use to relate current talk to previous interactions

One technique is repetition either verbatim, partially or paraphrase

Repetition

allows people to stall while formulating their talk

Provides redundancy to hearers as an aid to comprehension and connecting turns of talk

has varied interactional purposes such as

• controlling the floor,

• demonstrating active listenership

• ratifying the previous speakers talk

• showing or appreciating humour

• emphasizing one’s own or another’s contribution

sends a message of rapport

Conversational Postulates

assumptions about the situation and co-participants based on cultural models of interaction, of the fit between behaviour and context and of people’s rights and obligations

cultural norms also dictate what can be said and what should not be said in particular situations as well as the ways to say what can be said

If interlocutors belong to the same culture, none of these assumptions need to be stated or even consciously recognized; they are learned and presupposed in daily life

Gina: Hey Angela! So are you gonna have a baby next year? (Yup, she went right for it - she knows about my miscarriage so I guess she was just trying to make conversation? I dunno…)

Me: Oh, hello Gina.I don’t know, maybe - we’re not in a rush or anything.

Gina: Oh, that’s good.You shouldn’t have a baby next year - it’s the year of the rat. If you have a baby, your baby will be a rat (she is asian and I guess she follows chinese astrology).

Wait until 2009, that’s the year of the ox.

Me: (irritated that she said my baby would be a rat! wtf???) Oh, thanks for sharing. Yeah, I don’t know when we plan on having a child but whatever happens, happens. (and I’m certainly not going to wait just because she said so!)

Conversational Postulates

Most people cooperative in social encounters

Participants have common aims to make mutually dependent contributions to conversation

some agreement on purpose of the conversation

Conversation should be informative

(quantity) – as much info as needed

Conversation should be truthful , sincere (quality)

Relation – must be relevant

Manner – should not be obscure, ambiguous, must be brief and orderly

We can’t always be truthful, relevant, informative or coherent

Social constraints might require us to tell a white lie – but may be relevant to the function of the conversation .e.g. Maintaining in relationship

If we know we are breaking the rule it is important to maintain the relationship by acknowledging the violation

use linguistic devices as prefaces to statements to signal or acknowledge theory violations of presupposed maxims

• I’m probably totally wrong on this but

• I don’t want to get too far off topic but I’m not sure if this is relevant but

• I don’t know if this makes any sense but

• It’s difficult to state this clearly

Directives

requests for action intended to result in an action by the hearer

Based on several assumptions about the relationship

speaker wants hearer to do act

speaker assumes hearer is able to do act

speaker assumes hearer is willing to act

speaker assumes hearer will not do act in the absence of the request

Can you stay out?

Would you be willing to stay out?

Will you stay out?

These directives are either statements or questions – not a bald order - Stay out

Hearers are expected to react to obey and not answer the question

Directives have to be seen as reasonable and sincere

Hearer can challenge the directive by questioning underlying assumptions or by denying assumed conditions

why do you want me to stay out? It’s safe in there

The playground is closed , so I need to play in the quarry

why do think I’d be willing to stay out?

you don’t have to tell me to do it. I was just going to stay out anyway .

Higher status speakers are less often challenged by lower status people regardless of their remarks or when issuing directives

And regardless of the inconvenience of complying

speakers should phrase directives so as to have the greatest likelihood of compliance

Therefore they are sensitive to context and the relationship between speaker and addressee

But because a social relationship of some sort exists between interlocutors (even if one is a stranger), speakers must be sensitive to addressee’s feelings

An issuer of must make the request clear enough so that the addressee comprehends the directive intent, but must also pay attention to the addressee’s needs not to be imposed on by a blunt presumptions of the speaker’s power.

Can I have your number

I want you to open your book at page 3

Alternatives for issuing directives

Need statement ( speaker asserts her need or want)

I need you to open your book at page 3

Imperative (speaker commands an action of hearer

open your book at page 3

Embedded imperative (command is embedded in another linguistic frame

Could you open your book at page 3 ?

Permission directive (speaker asks permission, implying action of heaer)

If you would open your book at page 3?

Question directive (speaker asks a question, indirectly implying action of hearer)

Can open your book at page 3?

Hints (Speaker makes assertion, hinting a request)

It might be a good idea to open your book at page 3

mitigation

Markers of politeness that minimize the force of directives

May I please have the salt?

“would you be so kind as to give me the salt”

Speakers select among linguistic alternatives for directives based on context and on relationship with addressees

politeness and mitigation are generally used by speakers who are subordinate to addresses or who for reasons either of context or personality, wish to soften the force of a directive

bald imperatives may emphasize a person’s rights to command addresses (e.g. Towards children) but are seen as inappropriate, impolite and threatening

Mitigating linguistic devices

Interrogative: - could you mow the lawn?

Negation – l wonder if you wouldn’t mind mowing the lawn?

Past tense - I wanted to ask you0 to mow the lawn

Embedded “if” clause: - I wonder if you could mow the lawn

Consultative devices (indirectly asking for addresses cooperation): do you think we could mow the lawn?

Understaters (minimizing requests) -

Could you mow the lawn before I start?

Hedges (avoiding commitment): It would really help if you could mow the lawn

Downtoner (signalling possibility of noncompliance) : Will you perhaps be able to mow the lawn?

Hedges

mitigating devices used to lessen the impact of an utterance and avoid responsibility for underlying implications.

Typically, adjectives or adverbs, but can also consist of clauses.

He is a slightly stupid person. (adverb)

There might just be a few insignificant problems we need to address.

(adjective)

The party was somewhat spoiled by the return of the parents.

(adverb)

I'm not an expert but you might want to try restarting your computer.

(clause)

Hedges help speakers communicate more precisely the degree of accuracy and truth in assessments.

For instance, in “All I know is smoking is harmful to your health”, all I

know is a hedge that indicates the degree of the speaker’s knowledge instead of only making a statement, “Smoking is harmful to your health”.

Responses to requests

addresses select among alternative means of responding

If an addressee intends to comply with a request, a direct response is usually given

Non-compliance is usually accomplished indirectly

Since the social nature of conversation requires participants be cooperative refusals of directives typically contain a justification for refusal .

Often the refusal is related to the validity of the request

Is there a need to mow the lawn?

Can the person comply to the request

Does the speaker have the right to make the request

Bald challenges – NO - can be seen as confrontational and are usually mitigated

Telephone Conversation

Similarities with face-to-face conversation

based on structure of turn taking

usually begins with a greeting

develops into one or more topics and ends with a formulaic closing

Differences

have to rely on auditory cues and messages – not visually cues in understanding .e.g. no facial or bodily gestures that may alter the meaning

recognition is through sound of voice or name recognition

greetings, topic introductions and developments and closings differ somewhat in structure and in interaction

Caller Hegemony

The asymmetry between caller and answerer, because a caller controls the communication she/he has with the answerer

face-to-face begins with a mutual co-response, telephone conversation begins with a caller issuing a unilateral summons i.e. by making the call - thus interrupting the activities of the addressee even rest

by this beginning the caller is in an advantageous position – the call is planned

you can choose not to answer (especially with caller ID, but that decision is often based on a social reason i.e. wishing not to interact with a particular person at that time.

Most people answer

Caller also knows the identity of the addressee, or at least of the intended addressee

the caller is in the position of offering the first topic - i.e. the reason for the call

while caller ID mitigate the

"power" of the caller caller hegemony is maintained it is the caller who begins the conversation.

while we tend to "screen" callers with our cellphone's caller ID, our first reaction is not to like being screened.

We are managing two sets of communication (social) contexts: the physical context and the mediated context

Telephone conversation sequence

At the beginnings and at the ends of telephone conversations there are adjacency pairs - hello - hello and goodbye - bye

Answerer responds to the summons of the caller with a voice sample

- Hello

Caller responds with by providing a voice sample in the form of an identification of the addressee – Hi it`s Jane

Second set of utterances function as routine openers and markers of social interaction - greetings initiated by the caller `how are you` “fine” or “good”

Degrees of familiarity between caller and answerer affect the content of these turns

e.g. calling a business the caller may first identify him or herself by name before stating the reason for the call

greeting exchanges (how are you) likely to be omitted

name identifications omitted in people who are familiar going straight to greetings

Concepts of Politeness

Politeness...

“ … is one of the constraints of human interaction, whose purpose is to consider other`s feelings, establish levels of mutual comfort, and promote rapport.” Hill et al. (1986:

282)

“ … what we think is appropriate behaviour in particular situations in an attempt to achieve and maintain successful social relationships with others.“ (Lakoff 1972:

910)

Politeness

It is more important in a conversation to avoid offense than to be clear

politeness is another level to conversational interaction besides the rules of the cooperative principle

In most informal conversations, actual communication of important ideas is secondary to reaffirming and strengthening relationships

Lakoff’s postulates for politeness

• Don’t impose

• Give options

• Make A feel good – be friendly

Don’t impose

“dinner is served”

does not intrude on the addressee`s wants and needs

Interpersonally distant

Whereas with “would you like to eat? The person is addressed directly

passive constructions ``like`` is more polite than direct questions

Give options

Speakers giving options by using hedges and mitigated expressions that allow hearers to form and hold their own opinions

hedges and mitigation blunt potential confrontations

hearers can respond affirmatively or negatively

“I guess it’s time to leave now”

Make A feel good – be friendly

implies that speakers share similar models and norms for behaviour and that they evaluate speech according to the same presupposed notions

polite behaviour is based on assumptions of cooperation because all social groups need to minimize conflict among members

Politeness is concerned with “face”

Concept of "face"

"face"

public self-image that every member of society wants to claim for itself

negative face refers to the want of every competent adult member that his actions be unimpeded by others

positive face refers to the want of every member that his wants be desirable to at least some others

politeness strategies develop to deal with face-threatening acts

What threatens face, or what sort of persons have rights to face-protection is culturally relative.

Positive Politeness

Positive Politeness is redress directed to the addressee's positive face, his desire that his wants should be thought of as desirable.

Redress consists in partially satisfying that desire by communicating that one's own wants are in some respects similar to the addressee’s wants.

politeness strategies express solidarity, friendlinees, in group reciprocity

The linguistic realizations of Positive Politeness are in many respects representative of the normal linguistic behavior between intimates

Negative politeness

• Redressive action addressed to the addressee´s negative face

• Addressee wants to have his freedom unhindered and his attention unimpeded

• Specific and focused to minimize the particular imposition that the FTA effects

• Negative strategies express Speaker`s restraint and avoidance imposing on Hearer

• requests necessarily impose on Hearer’s negative face – desire to be unimpeded

• The most elaborated and the most conventionalized set of linguistic strategies for FTA redress (“Knigge“)

Face-Threatening-Activity

FTAs

= those acts that by their nature run contrary to the face wants of the addressee and/or of the speaker`s

The negative face is threatened by...

…acts that appear to impede the addressee ´ s independence of movement and freedom of action

The positive face is threatened by…

…acts which appear as disapproving of their wants

the more threatening an act is, the more polite and indirect are the means used to accomplish it

requests that involve minimal cost to Hearer are made through positive politeness strategies, stressing solidarity between Speaker and Hearer

requests involving greater imposition on Hearer are made through negative politeness strategies that are more formal and distancing

the most imposing requests are expressed through indirection and hints.