MEDIA’S EFFECT ON THE PREVALENCE OF EATING DISORDER Stephanie Lynne Kvasager

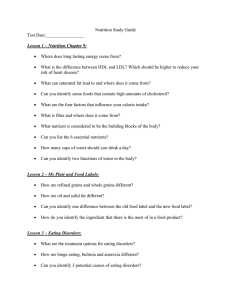

advertisement