CALIFORNIA WORKERS’ COMPENSATION SIU INVESTIGATOR REFERENCE MANUAL Christine Diana Wilson

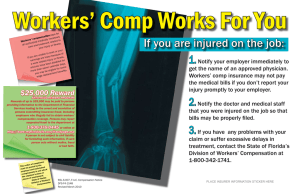

advertisement