ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN MALTREATMENT AND EMOTION DYSREGULATION IN YOUNG CHILDREN A Thesis

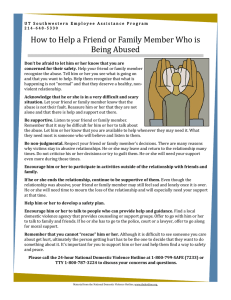

advertisement