EVALUATING ROAD SAFETY AUDIT IMPLEMENTATION AND

EFFECTIVENESS IN CALIFORNIA

A Project

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Civil Engineering

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

in

Civil Engineering

(Transportation Engineering)

by

Amanda Jordan Lee

SPRING

2014

© 2014

Amanda Jordan Lee

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

EVALUATING ROAD SAFETY AUDIT IMPLEMENTATION AND

EFFECTIVENESS IN CALIFORNIA

A Project

by

Amanda Jordan Lee

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Ghazan Khan

__________________________________, Second Reader

Dr. Kevan Shafizadeh, P.E., PTP, PTOE

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Amanda Jordan Lee

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the project.

_____________________, Graduate Coordinator

Dr. Matthew Salveson, P.E.

Department of Civil Engineering

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

EVALUATING ROAD SAFETY AUDIT IMPLEMENTATION AND

EFFECTIVENESS IN CALIFORNIA

by

Amanda Jordan Lee

Road Safety Audits (RSAs) are formal safety performance examinations of an existing or

future road or any project, which interacts with road users, in which an independent,

qualified multidisciplinary team reports on accident potential and safety performance. It

estimates and reports on potential roadway safety issues for all users and identifies

opportunities for improvements to eliminate or reduce problems. Emphasis is placed on

preventive measures and implementing road safety into projects.

California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) recommends RSAs be implemented

and suggests following U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway

Administration guidelines; however, these guideline have not been made a standard

program for California. The objective of this research was to learn about the experiences

of transportation agencies implementing RSAs in California and to identify issues to

determine if improvements can be made in the agencies’ process.

v

A list of transportation agencies in all California counties, as well as various cities and

towns in California, was compiled and a survey was developed and distributed which

included 36 questions to collect data on agency implementation of RSAs. Survey

responses were compiled to create a dataset which was analyzed to identify best

practices, issues, and recommendations for future improvements to RSA implementation

in California.

The focus of the data analysis from survey responses was on entities that were currently

conducting RSAs. Of the 98 responding agencies, 68 (69.4%) were aware of what an

RSA is and 30 (30.6%) were not. Of the 68, almost 50% were actually conducting RSAs.

According to the data analysis, the most prominent issues that California transportation

agencies faced were a lack of standardization of the RSA process, lack of funding, and

lack of training. All of these issues are a critical part of the project findings that are a

priority in the recommendations of this project. A standard practice for conducting RSAs

would increase productivity and effectiveness. RSAs would be more productive and costeffective with proper training and implementation in California based on the

recommendations in this research. Lastly, availability of more funding would result in

more participation, training and implementation leading to safer roads in California.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Ghazan Khan

_______________________

Date

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Khan and Dr. Shafizadeh for their help and guidance in the

completion of this project, including help with survey implementation. I am thankful to

all the transportation agencies who responded to my survey. Their responses allowed me

to collect the data necessary to complete this project. I would also like to thank my family

and friends for giving me the support I needed to complete the graduate program. Special

thanks to my mom for helping me through to the end! I have grown so much from this

project and have enjoyed the learning experience from taking the extra time to complete

it.

vii

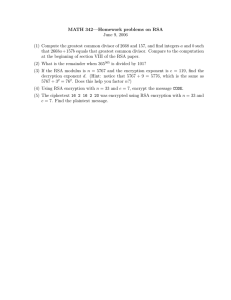

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... vii

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. xi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Definition .................................................................................................... 1

1.2 Problem Description ................................................................................... 1

1.3 Purpose of Study ........................................................................................ 4

2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 5

2.1 Road Safety Audit Implementation ........................................................... 5

2.2 Essential Elements of Road Safety Audits.................................................. 6

2.3 Conducting Road Safety Audits ................................................................. 7

2.3.1 Step 1: Identify Project or Existing Road to be Audited ............. 8

2.3.2 Step 2: Select RSA Team……………………………………… 10

2.3.3 Step 3: Conduct a Pre-Audit Meeting…………………………. 10

2.3.4 Step 4: Conduct Review of Project Data and Perform Field

Review..…………………………………………………11

2.3.5 Step 5: Conduct Audit Analysis and Prepare Report of

Findings……………………..………………………….11

viii

2.3.6 Step 6: Present Audit Findings………………………………... 12

2.3.7 Step 7: Prepare a Formal Response…………………………... 13

2.3.8 Step 8: Incorporate Findings Into the Project………………… 13

3.

LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................... 14

3.1 First Implementation of Road Safety Audits ........................................... 14

3.2 Case Studies .............................................................................................. 15

3.2.1 South Dakota.............................................................................. 16

3.2.2 Tribal Road: Navajo Nation ....................................................... 19

3.3 California Road Safety Audits .................................................................. 22

4. DATA COLLECTION ......................................................................................... 23

4.1 Agency Survey ......................................................................................... 23

4.1.1 Part A ……………………………………………………….

25

4.1.2 Part B………………………………………………………… 26

5. DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS ................................................................... 27

5.1 Survey Respondents ...................................................................................27

5.2 Questions and Analysis of Agencies Conducting RSAs............................34

6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................... 46

6.1 Survey ...................................................................................................... 46

6.2 Road Safety Audit Difficulties.................................................................. 46

6.3 Implementation of Road Safety Audits..................................................... 48

6.4 Primary Issues……………… ..................................................…………. 50

ix

6.5 Recommendations ....................................................................…………. 51

Appendix A. Survey Contact Information .................................................................. 53

Appendix B. Web-Based Survey ................................................................................ 61

Appendix C. Web-Based Survey Results .................................................................. 69

References ................................................................................................................... 76

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1.

National RSA Activity in 2011 …………………………………………… ….3

2.

Typical RSA Process ...........................................……………………………. 8

3.

Road Safety Audits Grouped by Phase and Stage ..…………………………. 9

4.

Recipient Distribution across California ................…………………………. 24

5.

Breakdown of RSA Survey…………………………………………… .....….27

6.

Web-Based Survey Results…………………………………………… .....….28

7.

City/County/Town Representation………………………… ..........................28

8.

Agencies Area Classification…………………………………………… .......29

9.

Percentage of Agencies Aware of RSAs by Classification……………… .....30

10.

Agency RSA Training .....................................................................…………31

11.

Breakdown of Agencies Conducting RSAs by Area Classification …………32

12.

Reasons for Not Using RSAs.................................…………………………. 33

13.

RSAs Conducted in the Last 3 Years……………… .....................…………. 35

14.

Roadway Types Included in RSAs……………… ........................…………. 36

15.

Time Frame for Conducting RSAs……………… ........................…………. 37

16.

RSA Team Composition……………… ........................................…………. 38

17.

RSA Checklist Used by the Agencies………………....................…………. 39

18.

Time Frame for RSA Field Review……………… .......................…………. 40

19.

Formal Response to RSA Team Recommendations……………… ................41

xi

20.

Agency Reasons for Not Implementing RSA Team Recommendations…… .43

21.

Data Collection for Evaluation……………… ..............................…………. 44

xii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Definition

Road Safety Audits (RSAs) are formal safety examinations of an existing or future road

or project that interacts with road users, in which an independent, qualified

multidisciplinary team reports on crash potential and safety performance. With a

proactive nature, RSAs estimate and report on potential roadway safety issues for all

users and identify opportunities for improvements to eliminate or reduce problems.

Emphasis is placed on the implementation of road safety using preventive measures.

The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), Federal Highway Administration

(FHWA) Guidelines state that RSAs are not a replacement for design quality control,

traffic impact studies, safety conscious planning, or standard compliance checks. They

should not be used to evaluate design work, rank one project over another, or evaluate

crash data and crash patterns (Ward, 2006).

1.2 Problem Description

The toll from traffic crashes remains a major health and economic problem in the United

States, signifying the need for improving the safety of roads. Safety is often lumped into

a large category of design criteria and is sometimes overlooked given all of the

components (e.g. alignment, drainage, utilities), when it should be one of the major

focuses of roadway design. In order to have a reduction in crashes there must be

2

consideration when designing roadways to include crash prevention, which requires

safety checks and audits. RSAs are an effective supplemental tool, which can help

achieve higher levels of safety especially in cases where safety issues may otherwise be

overlooked.

RSAs are being implemented across the world within formal safety programs. In 1996,

FHWA became aware of the need to facilitate and integrate RSA concepts into

engineering practice, and it developed a document that included RSA guidelines and

checklists (Lipinski & Wilson, 2006).

Increased availability of guidelines, training, and documentation of RSA fundamentals,

has led to more states performing RSAs. In January 2011, there was a study done by

FHWA that determined at least half of the states in the U.S. were piloting or performing

RSAs, as shown in Figure 1 (Nabors et al., 2012). In addition, many of the states had

implemented standard RSA programs.

3

Figure 1: National RSA Activity in 2011

(Nabors et al., 2012)

California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has developed a “Local Roadway

Safety Manual for California Local Road Owners” to assist local agencies in conducting

proactive safety analysis of roadway networks. The goal for developing this manual,

according to the manual itself (Local Roadway Safety Manual), “is to maximize the

safety benefits for local roadways by encouraging all local agencies to proactively

identify and analyze their safety issues and to position themselves to compete effectively

in future Caltrans’ statewide, data-driven call-for-projects” (Caltrans, 2013, p. 2). Within

this manual, Caltrans recommends RSAs be implemented and recommends following

FHWA guidelines; however, it has not been made a standard program for California.

4

There is little information on whether or not the different cities, counties, and towns in

California are implementing RSAs. In addition, if cities, counties, and towns are

implementing the audits, there is little information on the process and whether or not

FHWA guidelines are being followed. Without a standard program, the implementation

process and effectiveness of the individual programs throughout the state is unknown.

1.3 Purpose of Study

The primary goal of this project was to identify issues that California transportation

agencies were facing when conducting RSAs and to develop recommendations that

would help improve the process so that a standard program can be developed. The data

collection for this study included 448 county, city, and town transportation agencies in

California first to determine if RSAs were being implemented, then to what extent and

how effective were the RSAs. The product is a discussion, which includes the differences

in the agencies’ RSAs, the outcomes of conducting RSAs, and a recommendation for

future RSAs. With improvements to the RSA process, a standard could become better

integrated into California’s Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP), similar to what other

countries have done as discussed in Chapter 3 of this report.

5

Chapter 2

BACKGROUND

2.1 Road Safety Audit Implementation

Integration of RSAs into an agency’s road safety management plan requires involvement

from all levels of an organization. There must be management commitment to pilot the

RSAs and develop a formal RSA policy. Project managers must be informed and they

must continue to put individuals through training programs. The organization as a whole

must continuously monitor and refine their RSA policy to ensure the policy is successful

and providing effective safety benefits to their problem areas (Ward, 2006). The FHWA

Guidelines states, “RSA champions, who will devote energy to driving the RSA

implementation forward and who are empowered by management to do so, are critical to

getting a successful RSA program started” (Ward, 2006, p. 3).

Agencies can initiate the RSA process by conducting pilot projects. A pilot project is a

trial that will provide the ability to learn the process and test the logistics. Agencies do

not have the time, staff or money to conduct something that may have deficiencies, no

effectiveness, or that is not going to be cost-effective. The pilot projects would involve

professionals that would lead future RSAs and project managers who would incorporate

recommendations from the RSA report into an existing or future project. The agency

should designate an RSA coordinator that has an understanding of the RSA process and

road safety engineering.

6

With experience from the pilot projects, agencies can develop a formal RSA policy. As

FHWA guidelines states, “Key elements of a formal RSA policy include: Criteria for

selecting projects and existing roads; Procedures for conducting and documenting RSAs

and Response Reports; and Programs for providing RSA training” (Ward, 2006, p. 4).

Through training programs, RSA programs would have skilled auditors that are

knowledgeable about the implementation.

After an agency has developed a formal RSA policy, they need to keep monitoring and

refining it in order to get the most beneficial safety program. Management wants

effective low cost safety benefits, and if there are benefits and success, it should be

shared throughout the agency so that the RSA process continues.

2.2 Essential Elements of Road Safety Audits

An RSA has essential elements that make it different from any other safety review. As

Ward (2006) states in the FHWA Guidelines the essential elements are as follows:

1. The nature of the RSA implementation is proactive. Rather than performing a

safety review as a reaction to a problem, an RSA is conducted to prevent a safety

issue from occurring.

2. The nature of the RSA product is qualitative. The product identifies issues and

suggests preventive measures.

7

3. It has a formal examination that requires the audit team to follow a formal policy

set forth by the agency. It includes a formal review and report.

4. The RSA is conducted by a multi-disciplinary independent qualified team. The

team is made up of a variety of experience and expertise and they are independent

of the design team involved in the original design.

5. The RSA focuses on road safety issues and includes all road users. Lastly, field

reviews are always conducted and typically are done both day and night.

2.3 Conducting Road Safety Audits

The Road Safety Audit process has typical steps for agencies to follow. According to

Ward (2006) in the FHWA guidelines, the process takes eight steps:

Step 1: Identify project or existing road to be audited

Step 2: Select RSA Team

Step 3: Conduct a pre-audit meeting

Step 4: Conduct review of project data and perform field reviews

Step 5: Conduct audit analysis and prepare report of findings

Step 6: Present audit findings

Step 7: Prepare formal response

Step 8: Incorporate findings into the project when appropriate (Ward, 2006)

The eight steps are conducted by either the RSA team or the design team/ project owner;

they are illustrated in Figure 2 on the following page.

8

Figure 2: Typical RSA Process

(Nabors et al., 2012)

2.3.1

Step 1: Identify Project or Existing Road to be Audited

The first step in the RSA process requires the project owners to determine which road or

project is going to be audited, and when. There are multiple stages for transportation

facilities and an RSA can be conducted on any of them. In the United States, there are

four phases each with a varying number of stages. The four phases are pre-construction,

construction, post-construction, and development project. Pre-construction phase contains

three stages made up of planning, preliminary design, and detailed design. Construction

phase contains three stages made up of work zone stage, construction stage, and preopening stage. Post-construction phase contains one stage and that is existing roads;

roadways that have been opened. Lastly, development project phase contains one stage

and that is land use development (Ward, 2006). Land use development is the conversion

9

of land into construction ready, involving improvements to drainage, grading, or paving.

Figure 3 illustrates the grouping method of the phases and stages.

Figure 3: Road Safety Audits Grouped by Phase and Stage

(Ward, 2006)

The first phase, pre-construction, involves RSAs that are conducted before the

construction of a facility begins. Changes can easily be made with less of an impact to the

cost and schedule of the project. The second phase, construction, involves RSAs that are

conducted after the project design phase when construction either is about to begin, has

begun, or is recently completed. These RSAs typically ensure the construction zone and

final design are safe before opening to the public. The third phase, post-construction,

10

involves RSAs that are conducted on existing roads. This phase of an RSA is different

from the others, as its main objective is to identify road safety issues for all road users.

The fourth phase, development project, involves RSAs that are conducted on land

development projects such as industrial, commercial, or residential that can have an

impact on the adjacent roads.

According to FHWA Guidelines, it is important for the project owner to define the

parameters for the RSA once the roadway has been identified. The owner should include

a scope, schedule, tasks, and expectations (Ward, 2006).

2.3.2

Step 2: Select RSA Team

The second step in the RSA is selecting the multidisciplinary audit team, which is done

by the project owner. This team needs to be independent from the project owner and/ or

the design team. The members of this team must be qualified, knowledgeable about the

RSA process and road safety. The team should be made up of at least three individuals,

each having different expertise (design, traffic, maintenance, construction, safety, local

officials, police, first-responders) (Ward, 2006). With this team dynamic, the audit can be

more effective with identifying road safety issues.

2.3.3

Step 3: Conduct a Pre-Audit Meeting

The third step in the RSA involves both the project owner and the selected audit team. A

pre-audit meeting is held for the two entities so they can discuss scope and project

information. In this meeting, the topics discussed are the scope, project information,

11

schedule, tasks, expectations, and ways of communication. For the different RSA phases,

the project owner would need to give the RSA team specific information related to that

phase.

2.3.4

Step 4: Conduct Review of Project Data and Perform Field Review

The fourth step is for the audit team to conduct a review of the project data prior to going

out for a field review. The audit team would study the existing project information to get

an idea of what they might find in the field review. These preliminary project data

reviews are first done individually and then they are discussed as a team. Once a review

of material has been completed and the auditors are confident in their understanding of

the site, the field review is performed.

The field reviews can be done independently with a meeting to come together as a team

after or they can be done as a team from the beginning. During the field review, concerns

that were found in the review should be verified and photographs or video should be

taken for visual justification (Ward, 2006, p. 33). The audit team would identify the

safety issues to be further analyzed.

2.3.5

Step 5: Conduct Audit Analysis and Prepare Report of Findings

The audit team would continue from step four with identifying the safety issues to then

analyzing and finalizing their RSA findings in an RSA report. According to Ward in

FHWA Guidelines, the report should be concise and should be completed within a

relatively short amount of time (two weeks). The RSA report would be written to identify

12

the safety issues found on site along with the level of risk associated with it; and then a

recommendation to fix the safety issue would be presented. Recommendations should be

constructive, realistic, and appropriate for the project stage (Ward, 2006, p. 36). For

example Ward states:

In a pre-opening RSA in the Construction Phase, it would not be appropriate to

suggest making modifications to the vertical alignment of the roadway due to

sight distance issues approaching a STOP controlled intersection. Suggestions that

are more appropriate may be warning signs, rumble strips, or the removal of trees

to improve sight distance. Conversely, in a preliminary design RSA in the Preconstruction Phase, it would not be appropriate to suggest installing a guardrail

along a sharp curve. A more appropriate suggestion would be flattening the curve

itself.

These recommendations are going to be the most effective for the specific phase of the

project.

2.3.6

Step 6: Present Audit Findings

The sixth step is for the audit team to present the findings orally to the project owner/

design team. The audit team will not only discuss the safety concerns but also identify the

recommendations, which give opportunities for improving safety.

13

2.3.7

Step 7: Prepare a Formal Response

The seventh step is completed by the project owner, which involves a written response to

the RSA report findings. The written response is typically done in a letter report format;

and includes the project owner’s plan of action.

2.3.8

Step 8: Incorporate Findings Into the Project

The final step is for the project owner or design team to incorporate the RSA report

recommendations into the project, as they feel necessary and suitable.

14

Chapter 3

LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1 First Implementation of Road Safety Audits

According to FHWA’s Study Tour, RSAs were first introduced in the United Kingdom

(UK) by Malcolm Bulpitt in the 1980s (Trentacost, 1997). The Department of

Transportation’s report on the Evolution of Road Safety Audits states that the concept

evolved because they were experiencing high crash frequencies or severities on new

construction that could have been prevented if more safety-conscious designs were used.

“By 1991, the UK Department of Transport made RSAs mandatory for all national trunk

roads and freeways. National guidelines adopted in 1996 recommend that ideally all

projects should be subjected to a RSA if it is achievable, within available resources”

(Ward, 2006, p.65).

The Evolution of Road Safety Audits identified that by the early 1990s, RSAs were being

introduced in Australia and New Zealand. It noted that some individual states such as

Australia used their own policies to select projects for auditing, which seems to be the

trend in the United States. Through the 1990s, RSAs were introduced to other countries

such as Denmark, Canada, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and South

Africa. “In recent years RSAs have been actively implemented in the developing

countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh, India, Mozambique and United Arab

Emirates. Presently, the World Bank and European Transport Safety Council are actively

promoting RSAs as part of national road safety programs” (Ward, 2006).

15

FHWA recognized the potential for RSAs to become an effective proactive tool in road

safety management systems in the U.S. A tour was sponsored by FHWA to Australia and

New Zealand in 1996 in order to gather information to develop U.S. specific guidelines.

The conclusion of this tour was that RSAs show significant promise in maximizing the

safety of roadway designs and operations and should be piloted in the U.S. A major step

towards implementation of RSAs in the U.S. was the FHWA RSA pilot program (Ward,

2006, p. 65):

Pennsylvania DOT developed a program to implement RSAs at the design stages

of projects. New York DOT developed a program to integrate RSAs into their

pavement overlay program. Iowa DOT developed a program to integrate RSAs

into their 3R projects (pavement rehabilitation, restoration and resurfacing). The

first application of RSAs to a mega-project in the US occurred in 2003, when

designs for the Marquette Interchange upgrade in Milwaukee, Wisconsin were

audited. RSAs for existing local roads are also being conducted by the

Metropolitan Planning Commissions of New Jersey and Vermont.

Experience from the pilot RSAs indicated that they have a proven positive road safety

effect and should be further integrated into road safety management systems.

3.2 Case Studies

There are multiple case studies performed in the United States that provide documented

information and results of surveys from state and local transportation agencies. The

16

following sections go into further detail of case studies in South Dakota conducted by

local agencies and along tribal roads conducted by different tribes and state agencies.

3.2.1

South Dakota

The South Dakota Case Study presented in this section is according to Local Rural Road

Safety Audit Guidelines and Case Studies (South Dakota Department of Transportation,

2010). The South Dakota Local Transportation Assistance Program (SDLTAP) in 2010

selected multiple RSA projects through the promotion and commitment of the local

agencies; there were eight case studies conducted. Each case study selected RSA team

members that would be useful based on the characteristics and location of the project.

The study included county roads, townships, intersections, and railroad crossings within

several counties.

County Road: Day County Route 1

Day County Route 1 (447th Avenue) was a major collector running from the southeast

corner of Waubay, South Dakota. The selected portion of the road was approximately 2

miles in length, beginning approximately 4 miles south of town. The pavement surface

and pavement markings were in good condition. The posted speed limit was 55 miles per

hour (mph). The Average Daily Traffic (ADT) was estimated to be 400 + vehicles/day

with increasing traffic volumes. This road served local access traffic, agricultural traffic,

and recreational access.

17

At the time of the review, the audit team did not have access to crash data; however,

between 2006 and 2008 there were nine fatalities, six within the project review limits.

Safety was a growing concern due to the traffic speeds and limited sight distance.

After the RSA was conducted in April of 2009, the county commission passed a

resolution in June 2009 requesting funding assistance from the FHWA Highway Safety

Improvement Project (HSIP) to make construction and operational improvements. The

RSA and the final report were used as the primary supporting documents (Local Rural

Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Case Studies, 2010).

Intersections

The case study performed RSAs at two intersections in the City of Pierre. The first

intersection had a daycare facility at the corner of two major roads. The other intersection

of Church and Harrison had no sidewalk on the northeast corner of the intersection.

The purpose of the review for the first intersection was to address safety concerns related

to vehicles picking up and dropping off children. The other intersection of Church

Avenue and Harrison Avenue had been of interest because Harrison Avenue was

extended to be a through street to the north, serving a shopping mall and a residential

development, and a sidewalk was not installed; the potential for pedestrian conflicts had

grown.

With the RSA results, the City of Pierre redesigned the day care entrance and exit with

the main building access moved to the rear. For the Church and Harris intersection, the

18

City of Pierre added “yield to pedestrians in crosswalk” signs to all legs of the

intersection.

Railroad Crossings

The case study performed RSAs at two railroad crossings, the first had a potential for

crashes due to the skewed angle of the crossing. The second had a potential for vehicles

hitting the low-clearance structure. The railroad structure was over Pierre Street, which

was located between Sioux Avenue and Pleasant Street. The structure vertical clearance

was 11’3” (Local Rural Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Case Studies, 2010).

With the RSA results of the first location, Stanley County officials had placed Advanced

Warning Railroad Crossing signs. They were attempting to contact the railroad agency to

resolve tree trimming for improved sight distance. In addition, the 35 mph speed limit

was extended to reduce the speed before entering the curve that approaches the crossing.

For the second location, the City of Pierre intended to install low clearance detection

devices and warning system. Funding had been approved for the project.

There were many lessons learned with the performance of these case studies, which are

summarized as follows:

1. This project had increased awareness of local road and street safety in South

Dakota. When a highway superintendent or local manager is involved in the

review team, they gain experience and they return to their department with a new

perspective in analyzing traffic safety.

19

2. One of the key elements of RSA success is good preparation before performing

the audit. All of the information for the project site must be prepared and

discussed at the start up meeting.

3. Local governments in South Dakota are wary of the road safety audit process.

4. Some local officials are opposed to the term “audit” because it can have a

negative connotation in the minds of many people.

5. To overcome the reluctance to conduct formal RSAs, someone local that

understands the purposes and procedures of an RSA, and who is willing and able

to promote RSAs is needed.

6. It is good to have a diverse RSA team.

7. The team must understand functional classifications of local roads.

8. It is important to schedule an RSA field review during regular recurring traffic

conditions (Local Rural Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Case Studies, 2010, p.

24-25).

3.2.2

Tribal Road: Navajo Nation

The Tribal Road Case Study presented in this section is according to the Tribal Road

Safety Audits: Case Studies. The Navajo Nation and the Bureau of Indian Affairs studied

three segments of Highway N-12 and two intersections. Two of the segments were

located in rural areas and had a two-lane rural cross-section with paved shoulders. One

segment was located in an urbanized area with a five-lane cross-section with paved

shoulders or curb-and-gutter. The two intersections are signalized

20

Highway N-12 was a rural minor arterial, which provided access to the Navajo capital at

Window Rock, AZ. The RSA focused on the portion of N-12 north of Highway 264

between Window Rock and Fort Defiance, and two sites south of Highway 264.

Highway N-12 has an Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) ranging between 14,000

and 24,000 vehicles used by residents of the Navajo Nation reservation and visitors, as

well as, residents to commercial establishments in Window Rock. The highway

accommodated a substantial truck volume. Speed limits along the segments of roadway

vary from 35 to 55 mph (Gibbs, Zein, & Nabors, 2008, p. A-6).

Seven years (1999 through 2005) of collision summaries along N-12 were reviewed as

part of the RSA. A total of 386 collisions were reported along N-12. Annual collision

frequency peaked in 2002 with 60 reported collisions, and declined each subsequent year

to a low of 21 reported collisions in 2005. Data collected showed peaks around 23/24

Post Mile (PM) and 28/29 PM in the Window Rock and Fort Defiance areas (Gibbs et al.,

2008, p. A-14).

The audit identified a number of safety issues and the RSA team rated their risk on a

scale of A (being the lowest risk and priority) to F (being the highest risk and priority).

Highlighted in the case study, were risks C and above, which were given

recommendations for change. Examples of a few of the highest safety risks were:

Signing and pavement marking issues, pedestrian design and maintenance issues, poor

pavement conditions, and access to residential areas interfering with operations at the N12 intersection. These safety issues were identified and possible mitigation measures

21

were suggested. Suggestions focused on measures that could be cost-effectively

implemented within budget (Gibbs et al., 2008, p. 8).

As discussed in the Tribal Studies Safety Audits: Case Studies, the tribal RSA case

studies helped to identify six key elements that can help make an RSA successful.

1. The RSA team must acquire a clear understanding of the project background and

constraints.

2. Recurring concerns identified in multiple triple RSAs may reflect safety issues

typical of tribal transportation environments.

3. The involvement of multiple road agencies in the design, operation, and

maintenance of roads on tribal lands can present a challenge, and can help

promote a successful RSA outcome.

4. The RSA team and design team need to work cooperatively to achieve a

successful RSA result.

5. Someone that understands the purposes and procedures of an RSA, and who is

willing and able to promote RSAs can greatly help to facilitate the establishment

of RSAs.

6. The RSA field review should be scheduled during regular recurring traffic

conditions.

The tribal RSA case study project was sponsored by the FHWA Office of Safety and was

well received by the participating tribal transportation agencies (Gibbs et al., 2008, p. 1721). The case studies summarized the results of each RSA to provide the tribal

22

governments with examples and advice to assist them in implementing RSAs in their own

jurisdictions.

These case studies are referenced in Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 as they are consistent with

the results from the survey responses.

3.3 California Road Safety Audits

California local roads operate with outdated and/or insufficient safety features. According

to the Local Roadway Safety Manual, “Limited funding often prevents agencies from

constructing safety projects, which can be expected. At the same time, the lack of safety

data, design challenges, and lack of adequate training also hinders local agencies’

accurate evaluation of their roadway safety issues, which is more preventable” (Caltrans,

2013, p. 6). It is Caltrans’ responsibility to administer funding for local roadway safety

improvements. There are federal funding safety programs that are used at the state level,

such as the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) and the High Risk Rural

Roads Program (HR3). These safety programs are now including Road Safety Audits as

an eligible project.

23

Chapter 4

DATA COLLECTION

4.1 Agency Survey

In order to collect information on RSA implementation within the different cities,

counties, and towns in California, a web-based survey was sent out to 448 county, city,

and town local contacts of the transportation and/or public works departments. The goal

was to obtain enough data to determine whether or not agencies in California were using

RSAs, and if they were, how effective the agencies themselves found them to be. Of the

448 agencies, there were all 57 counties and 391 cities/towns. The distribution across

California can be seen in Figure 4. A detailed contact list can be found in Appendix A:

Survey Contact Information.

24

* City Recipients

Figure 4: Recipient Distribution across California

The survey included two parts, A and B. Part A was intended for information on the

RSAs being implemented, and Part B was intended for recommendations for future

RSAs. With Part A, the necessary information on agency implementation was determined

and with Part B, there was agency input to help with the recommendations for

25

California’s standard program. The survey can be seen in Appendix B: Web-Based

Survey.

4.1.1

Part A

The beginning of the survey asked for the local agency’s identifying information so that

the different responses could be categorized by city, county, or town. Next, the survey

asked the agency if they were aware of what a RSA is. This question would eliminate

those agencies that were not aware of RSAs. The survey then identified if the agency had

been through training and what type of sources the agency had used to learn how to

conduct RSAs. This question helped to identify whether or not the agencies knew about

the FHWA process or if they were more likely using their own standards. Next, the

leading question to the main survey was whether the agency had conducted any RSAs. If

the agency had not, there was a question asking to explain why and then they were exited,

but if they had, the survey continued.

The main body of the survey included questions that asked the following:

1. What types of projects are included?

2. When are the RSAs conducted?

3. Who is in the RSA team conducting the RSAs?

4. What was used when conducting field reviews?

5. How long do the RSAs take?

6. Are recommendations made, and if so are they implemented?

7. How is the success of the RSA measured?

26

4.1.2

Part B

The second part of the survey included questions that were intended for agency opinions

that would identify key elements for conducting a successful RSA. The questions

included:

1. When is the most beneficial time for conducting RSAs?

2. What is the best organization for the RSA audit team?

3. What is the most useful information to collect from a field review?

The data from the survey responses were collected and analyzed for standard program

recommendations.

27

Chapter 5

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

5.1 Survey Respondents

The web-based survey was sent to 448 agencies, including all 57 counties and 391

cities/towns. The total number of respondents was 98 (22%). Of the 98 respondents, 68

agencies were aware of an RSA, of those, 33 conducted them (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Breakdown of RSA Survey

The 98 respondents provided a good representation of the various counties, cities, and

towns of California (Figure 6 and 7) and included both rural and urban areas (Figure 8).

28

Figure 6: Web-Based Survey Results

Figure 7: City/County/Town Representation

29

Figure 8: Respondent Area Classification

Urban areas are cities/ towns that have a dense population with development of houses,

buildings, roads, and bridges. An urban area can refer to towns, cities, and suburbs. In

contrast, rural areas are all areas outside of the urban areas with low population density

and with large amounts of undeveloped land. Figure 8 above represents more rural

respondents than urban, most likely because they represent 75% of the California areas.

30

Of the 98 agencies, 68 were aware of RSAs and 30 were not. When looking specifically

at the urban and rural classification of all respondents, the data shown in Figure 9 shows

that, there were a higher percentage of urban agencies aware of RSAs than those in the

rural areas.

Figure 9: Percentage of Agencies Aware of RSAs by Classification

Urban areas may be more aware of planning and transportation issues due to their dense

population requiring more attention from government programs that assist them with

handling the changes caused by population growth and the need for improvements and

increased development.

31

For those respondents who were not aware of RSAs, they were exited from the survey

with an information link http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/guidelines/. The link was included

so they had a resource with more information that would familiarize them with FHWA

guidelines for conducting RSAs.

The next question in the survey was to find out whether the 68 agencies had any sort of

training on how to conduct RSAs. Of the 68 respondents, only 7% of agencies went

through federal training FHWA; 42% had other training through printed materials,

videos, other agencies, consultants, webinars, and workshops (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Agency RSA Training

Of the 68 respondents that were aware of RSAs, 33 agencies were conducting RSAs. Of

these 33 respondents, 73% had some sort of RSA training. Figure 11 shows that there

were nearly as many urban agencies (56%) as rural agencies (53%) conducting RSAs.

32

Figure 11: Breakdown of Agencies Conducting RSAs by Area Classification

It is likely that urban agencies are conducting RSAs because of their knowledge and

training of the transportation programs and the effectiveness of RSAs and therefore they

use them. It is likely that rural agencies are conducting RSAs because rural roadways

tend to lack safety features. RSAs are an effective tool to identify safety issues. If there

was more awareness about RSAs in rural areas, the probability of conducting them would

most likely increase. There is a greater need in the rural areas because they make up a

greater percentage of the roadways in California.

33

Figure 12 shows that lack of funding was the main reason agencies are not conducting

RSAs. Secondly, a lack of personnel was a major factor, which is most likely related to

not having funding.

Figure 12: Reasons for Not Using RSAs

Until recently, there has not been an emphasis for RSA funding within the roadway

safety grants. Data has proven, through conducting RSAs, that RSAs are beneficial and

effective in identifying roadway safety issues. It is expected that the number of agencies

conducting RSAs will increase and the lack of funding will no longer be an issue. This

would be an area worth re-evaluating after a few grant cycles.

34

Few agencies stated there was a concern for liability and a lack of interest in the RSA

process. As found in the lessons learned from the case studies in South Dakota the

perception from some local officials was that they were opposed to the term “audit”

because it could have a negative connotation in the minds of the people in the agency.

Also, some of the local governments were wary of the road safety audit process in that it

points out the safety issues and could be potentially seen as a liability to them. In

opposition to these claims, the RSA process is implemented in order to reduce the safety

liability to the agencies and incorporate preventive measures. It is not performed to

highlight the faults in the agency roadways but rather to provide recommendations for

improvements.

5.2 Questions and Analysis of Agencies Conducting RSAs

Once the survey established those agencies that conducted RSAs, the survey questions

became more specific to define the effectiveness of the agency’s RSA process and

outcomes. What follows is an analysis of the data provided by those agencies that are

currently doing RSAs.

Question: How many RSAs has your agency conducted in the last three years?

Analysis: Those that had responded with zero in the last three years, the assumption is

that they responded based on an RSA conducted more than three years ago. The data

indicates that most agencies have conducted between one and five RSAs in the last three

years. Few agencies have conducted more than five RSAs in the last three years (Figure

13). The responses reflect a good range of experience in performing RSAs.

35

Figure 13: RSAs Conducted in the Last 3 Years

Question: What types of roadways/sites are included in the RSAs?

Analysis: The majority of agencies performed RSAs on two-lane highways, local roads,

and intersections. They performed RSAs on multi-lane highways slightly less (Figure

14).

It is likely that these agencies conducted RSAs on two-lane highways, local roads, and

intersections because they have more conflict points, multiple modes of transportation,

and higher incident of accidents. According to the FHWA Safety website, “Rural

collectors and local roads tend to lack features such as paved shoulders, clear zones, and

divided directions of travel. Rural roads tend to have higher average vehicle speeds,

36

partially due to low volumes” (FHWA). Intersections can be problematic locations

because they are complex and require a higher demand on a driver. The three facility

types are conveying the most safety needs and therefore agencies are performing RSAs to

identify the issues and prevent traffic accidents. Nevertheless, the chart shows a mix of

various kinds of facilities and not just focused on a single type e.g. intersections which

are often times the perception in some circles.

Figure 14: Roadway Types Included in RSAs

37

Question: When does your agency conduct RSA audits? Do you think it is beneficial to

conduct the RSA at a specific phase?

Analysis: The data showed that the majority of respondents are conducting RSAs during

the Pre-Construction phase, which includes Planning, Preliminary Design, and Detailed

Design. Many respondents have conducted RSAs in other phases; however, the majority

recommended conducting them in the Pre-Construction phase.

Figure 15: Time Frame for Conducting RSAs

It is best to conduct RSAs during the Pre-Construction phase because it is most beneficial

to implement the recommendations made by the audit team early in the design phase. It

38

will mitigate future changes for construction or for the constructed project, which both

can be costly.

Question: What expertise(s) are included in the Road Safety Audit team?

Analysis: The data showed that the agencies include traffic and public works

representatives most often; however there was a variety of expertise that were critical to

the team. Often times, the limitation of expertise resources is due to the lack of funding.

The public works and traffic expertise is usually existing staff that deal with

transportation related tasks.

Figure 16: RSA Team Composition

39

Questions: Did the Road Safety Audit team perform field reviews using pre-defined

checklists? For those that have, were they adequate? Please define the type of checklist

used and what data collection items are included.

Analysis: The majority of respondents did not use a pre-defined checklist. The

respondents did not include detailed information on whether or not they were adequate

nor did they provide information on the data collection items/ checklists; therefore an

analysis on field review checklists and data collection could not be made.

Figure 17: RSA Checklist Used by the Agencies

40

Question: What is the average time frame for completion of an RSA? Was the audit team

timely in their responses?

Analysis: The data showed that 96% of the audit teams performed RSAs timely. Most of

the RSAs were conducted within a 6 month time frame, which is important for allowing

time for identifying key issues. The short time frame enables issues to be addressed

before the design phase is started or completed, which is more efficient and more cost

effective.

Figure 18: Time Frame for RSA Field Review

41

Question: Once the field review is complete, is a report developed with

recommendations? If so, does your agency prepare a formal response to the audit

recommendation report?

Analysis: A majority of the RSA teams developed a report with recommendations. After

the report was submitted and reviewed by the agency, the data showed that 73% of the

agencies did not respond with a formal response to discuss their reaction to the

recommendations. A formal response is important because it defines the agency’s

response to the findings. It should include the next steps the agency plans to take.

Figure 19: Formal Response to RSA Team Recommendations

42

Question: Did your agency implement the recommendations made by the Road Safety

team? For the recommendations not implemented what was the primary reason(s)?

Analysis: The majority of respondents (16 or 59.3%) implemented some of the

recommendations; 37.0 percent (10) agencies implemented all the recommendations and

only 3.7 percent (1) agency did not implement any recommendations. The most

significant reasons for not implementing recommendations were due to lack of funding

(budget) or lack of economic feasibility (Figure 19). The lack of funding relates to the

initial reasons why agencies do not conduct RSAs, the agency does not have funds to

place recommendations from the RSA team.

For a lack of economic feasibility to occur, the recommendations have a benefit cost ratio

less than one; the benefit is less than the cost. RSA field reviews are intended to

recommend cost-effective measures to improve safety. If respondents say that

recommendations are not economically feasible, perhaps these audit teams need to focus

on cost effective countermeasures. There were only three agencies with FHWA training,

perhaps if more agencies adopted this training to learn the process it would help RSA

teams identify cost effective countermeasures.

43

Figure 20: Agency Reasons for Not Implementing RSA Team Recommendations

Questions: Does your agency do any post-audit evaluation on the effects of the

implemented recommendations? Do they collect data to show evidence that safety has

been improved at the study location? In the end, is there evidence that safety has been

improved?

Analysis: These questions were analyzed together due to their correlation. In order to

have evidence that safety had been improved there must be some kind of evaluation

either through data collection or site reviews. The data indicated that 88% (21) of the

respondents collected data.

44

Figure 21: Data Collection for Evaluation

Of the 21 respondents that collected data, 16 stated that there was evidence of improved

safety, and 5 had not yet implemented the recommendations. The fact that they collected

data and saw safety improvements implies that they were doing follow up or post audits,

which is important because in order to determine if RSAs were effective there must be an

evaluation to conclude whether or not the recommendations/ implementations improved

safety.

Question: How does your agency measure the success of the RSA?

Analysis: This question was intended for respondents to discuss whether or not the RSA

process was effective for the RSA team to improve safety. The respondents answered

45

instead with how they measured the success of the implemented recommendations. Some

of the measurements of success were as follows: monitoring collision history, comparing

collision rates with previous rates, and customer feedback. Some of the respondents

described that the success of the safety measures are intuitive. Although the respondents

did not directly answer if the RSA process was effective, the evidence of improved safety

from those using it was proof that it does have a positive effect.

46

Chapter 6

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Survey

To initiate the research on implementation and effectiveness of RSAs, 448 surveys were

sent out to California towns, cities, and counties. The total number of survey respondents

was 98 and of these respondents, 68 were aware of RSAs. Of the 68 agency respondents,

33 agencies actually conducted RSAs. The findings and conclusions are primarily based

on the 33 respondent agencies that conduct RSAs because the main goal was to identify

issues that California transportation agencies were facing when conducting RSAs and to

determine how effective the RSA process was. The respondents who were not aware of

RSAs or who do not conduct them were included in the initial data analysis to determine

the reasons.

6.2 Road Safety Audit Difficulties

Although some of the agencies were not aware of RSAs, their responses indicated the use

of some level of road safety assessments. The fact that these agencies conducted some

level of road safety assessments indicated that safety is an important issue to them. There

is FHWA education and training on the RSA process available, but there needs to be

more outreach to agencies especially to the rural areas. The data show there is less

awareness in these areas, which may be because urban area planning and transportation

issues garnish more political attention due to their dense population, high daily traffic

47

volumes and need for improvements for growing development. Rural areas make up a

greater percentage of the roadways in California and lack safety features, so they need to

be included in the government outreach for funding. An emphasis on outreach and

training from FHWA to provide awareness through education of the RSA process and its

effectiveness along with funding would demonstrate to the rural agencies that they are a

priority and would encourage implementation of a standard program.

For those agencies that were aware of RSAs, only 7% of the 68 respondents had FHWA’s

official training. California would benefit immensely if more outreach were done to

provide this training. Lack of standardized training could be a defining reason for why

many of the agencies do not conduct RSAs, or for those that do, why there is a lack of

implementation of the recommendations from the audit teams. If there is a lack of

knowledge of the process then many agencies are not going to implement a standard RSA

program and will not make it a priority within their agency. With appropriate training, the

agencies would learn that the RSA is an effective tool to improve roadway safety in a

cost-effective manner and promote proactive safety improvements.

Based on the 68 survey responses, 69% of the agencies stated they did not use RSAs

because of the lack of funding and lack of personnel. Many cities do not have the funds

for transportation related projects and in order for agencies to implement the RSAs there

needs to be a source of funding and personnel. Through FHWA, there are federal funding

safety programs that are used at the state level, such as the Highway Safety Improvement

Program (HSIP) and the High Risk Rural Roads Program (HR3). These safety programs

48

are now including Road Safety Audits as an eligible project. It is important that federal

and state government start to prioritize RSA funding because as the funding resource

grows so will the agency involvement.

6.3 Implementation of Road Safety Audits

The majority, or 76%, of agencies that were conducting RSAs were conducting them on

local roads, intersections, and two-lane highways. The phase for conducting was typically

done within the Pre-Construction phase. The agencies also stated that the PreConstruction phase is the most beneficial (more cost-effective) phase to conduct RSAs

because the recommendations made by the audit team can be implemented into the

design early. It will mitigate future changes to the design or future changes to the

constructed project, which both can be costly. The data showed that 96% of the audit

teams performed RSAs timely. Most, 76%, of the RSAs were conducted within a 6

month time frame, which is important for allowing time for identifying key issues. The

short time frame enables issues to be addressed before the design phase is started or

completed, which is more efficient and more cost effective.

When an audit team is developed, the expertise most often included was Public Works

and Traffic. For future audits, the majority of respondents felt additional expertise would

be beneficial to make the audit more effective, such as local officials. Local officials

should be used to make a better team especially considering the importance of local

knowledge in conducting RSAs. In fact, the South Dakota case studies found that the

RSA team must have a clear understanding of the project background and constraints and

49

functional classification of the local roads. It would be beneficial to have a local official

on the team because they have that background knowledge and can ensure that this

knowledge is provided to the team.

The most important part of the audit team structure is to have multiple disciplines to get a

broad perspective on safety for the project site. The issue gets back to a lack of funding.

Again, if funding were prioritized towards transportation safety this could help alleviate

the problem. Not only does the priority for funding need to be there but also the

commitment from management and an agency as a whole. As found in the FHWA

guidelines, “RSA champions, who will devote energy to driving the RSA implementation

forward and who are empowered by management to do so, are critical to getting a

successful RSA program started” (Ward, 2006, p. 3).

The majority of audit teams prepared a report with recommendations; however, 73% did

not always prepare a formal response. A formal response is important because it defines

the agency’s response to the findings. It should include the next steps the agency plans to

take. Respondents said that the recommendations were implemented but often times only

partially. The main reason for not implementing recommendations was budget. If the

audits are done in the Pre-Construction phase then these recommendations can be

incorporated into construction costs.

Some sort of data collection was reported by 67% of the respondents after the audit

teams’ recommendations have been implemented, so they do some sort of post audit

evaluation for evidence of safety improvements. The RSA is a cyclical process, in that,

50

when you implement the safety elements it is important to measure and evaluate the

success of the implementation. The measurement of success is typically confirmed by

post audit data collection and re-evaluation.

6.4 Primary Issues

The most prominent issues that were identified from this study were the lack of

standardization of the RSA process, federal training, and funding. All of these issues are

a critical part of the project findings that are a priority in the recommendations of this

project. In order to make the RSA process successful and effective for more agencies, it

would be beneficial to incorporate a standard practice. A standard practice for conducting

RSAs would increase productivity because it would reduce the learning curve. When

there are no standards, there is a greater chance for inconsistencies and errors. In

addition, it makes it difficult for establishing or providing training.

After an agency has developed a formal RSA policy, they need to keep monitoring and

refining it in order to get the most beneficial safety program. Management wants

effective low cost safety benefits and so if there are benefits and success, it should be

shared throughout the agency so that the RSA process continues.

With a standard practice there must be training to those who will be involved with the

implementation within the agency and training for those who will be conducting the

RSAs. With proper training, an effective RSA will be performed and cost-effective

measures will be implemented.

51

Funding is a leading concern for these agencies. If there was more funding available and

RSAs were a greater priority there would likely be more involvement. From the survey

result, those agencies conducting RSAs stated they find them effective. Of the 33

respondents conducting RSAs, 21 respondents collected data. Of these 21 agency

respondents, there were 16 agencies that stated there was evidence of improved safety

and five agencies that had not yet implemented the recommendations. Of those that

collected data after implementing the recommendations, 100% stated that there was

evidence of improved safety. The fact that the agencies that are collecting data are seeing

safety improvements implies that the RSA process is effective. RSAs are an effective

supplemental tool, which can help achieve higher levels of safety especially in cases

where it would otherwise be overlooked. If funding was available for implementing

RSAs, there would be more participation, training, and implementation. Most

importantly there would be safer roads.

6.5 Recommendations

Based on this work the following recommendations are made.

1. Agencies should follow the FHWA Guidelines in order to gain an understanding

on the definition of a formal Road Safety Audit and the process.

2. Conduct RSAs during the Pre-Construction: Planning phase for the most benefit

(cost-effectiveness).

52

3. Incorporate pre-defined checklists for a basis of information that will give

guidance and reduce the possibility for missing critical items.

4. Perform post audit evaluations to measure and evaluate the success of the

implementation.

5. FHWA should organize and facilitate more standardized training sessions

throughout the nation for all agencies to attend. Not only should training include

the process, but also the benefits of these safety audits over other methodologies.

6. FHWA should provide incentives so that the agencies will use their standards to

conduct Road Safety Audits.

7. FHWA should collaborate with those agencies that use a different process for

conducting RSA to determine if they have components that may be worth

adopting in the FHWA guidelines.

53

Appendix A: Survey Contact Information

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

Appendix B: Web-Based Survey

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

Appendix C: Web-Based Survey Results

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

References

California County Public Works Directors. (n.d.). County Engineers Association of

California. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from http://www.ceaccounties.org/

FHWA. Implementing the High Risk Rural Roads Program. (n.d.). FHWA Safety.

Retrieved February 1, 2014 from

http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/local_rural/training/fhwasa10012/chap_2.cfm

FHWA. Road Safety Audits (RSA). (n.d.). FHWA Safety. Retrieved November 21, 2013,

from http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/benefits/

Gibbs, M., Zein, S., & Nabors, D. (2008, September 1). Tribal Road Safety Audits: Case

Studies . FHWA Safety. Retrieved November 21, 2 013, from

http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/tribal_rsa_studies/tribal_rsa_studies.pdf

Grosskopf, S., Labuschagne, F., & Moyana, H. (n.d.). Road Safety Audits: The Way

Forward. CSIR Research Space. Retrieved November 13, 1921, from

http://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/bitstream/10204/4380/1/Grosskopf_2010.pdf

Lipinski, M., & Wilson, E. (2006, January 1). Road Safety Audits in the United States:

State of Practice. Institute of Transportation Engineers. Retrieved November 21,

2013, from http://www.ite.org/Membersonly/annualmeeting/2005/AB05H0801.pdf

77

Nabors, D., Gross, F., Moriarty, K., Sawyer, M., & Lyon, C. (2012, October 1). RSA

Case Studies. Road Safety Audits: An Evaluation of RSA Programs and Projects.

Retrieved November 21, 2013, from

http://www.vhb.com/508/RSACaseStudies/index.htm

Public Works Officers Directory. (2013, January 1). League of California Cities.

Retrieved November 21, 2013, from http://www.cacities.org/

Road Safety Audits. (n.d.). National Indian Justice Center. Retrieved November 21,

2013, from

http://www.nijc.org/pdfs/Road%20Safety%20Audit%20Training/Introduction%20to

%20Road%20Safety%20Audits%20-%20197%20pages.pdf

Road Safety Audits: An Emerging and Effective Tool for Improved Safety. (2004, April

1). Institute of Transportation Engineers. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from

http://www.ite.org/technical/IntersectionSafety/RSA.pdf

South Dakota Department of Transportation. Local Rural Road Safety Audit Guidelines

and Case Studies. (2010, June 1). Local and Tribal Technical Assistance Program

Website. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from

http://www.ltap.org/conference/2010/downloads/2010_SDPoster.pdf

Trentacost, M. (1997, October 1). Part 1. FHWA Study Tour for Road Safety Audits.

Retrieved November 21, 2013, from http://ntl.bts.gov/DOCS/rpt7-pt1.html

78

Ward, L. (2006, January 1). FHWA Road Safety Audit Guidelines. FHWA Road Safety

Audit Guidelines. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from

http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsa/guidelines/