The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics Meredith M. Price

advertisement

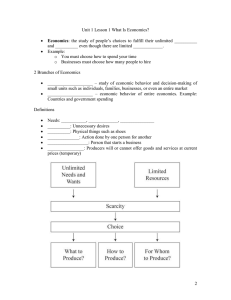

The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics Meredith M. Price The University Of Southern Mississippi The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 2 Abstract Mass media is suggested to be a catalyst toward economic impact. Studies posit that media information has either a negative and positive affect, which in turn can impact individual’s attitude. Consumer behavior research supports the idea that negative media content on the certain issues can cause the economy to fluctuate. This paper explores how mass media functions and how media concepts are related to economic impact. Research in media impact on the economy of the Mississippi Gulf Coast after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is the focus of study. Relating media and it’s impact on the economy is challenging but a necessary factor to study while in pursuit of understanding other factors in economic impact and media effects. The behavior of the economy can be impacted by how the media presents information towards the public. Introduction of mass media effects Print, radio, television, Internet, and social networks are common types of media. Media extends out to large masses of people and provides information to the public on various subjects, entertain, and to gratify people’s curiosities. As mass media has expanded and become more obtainable—cell phones, iTouch, and laptops—so have the influences on a person’s cognitive ability. It would appear that the individual has become more reliable on consulting the media. The news media is on a 24 hours and 7 days a week cycle. News is constantly streaming on the Internet through various websites and blogs. A widely accepted model of communication is the Westley-MacLean model of communication. It describes how information is gathered and disseminated to the audience (Severin The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics and Tankard, 2001). A closer look at the Westley-Mac Lean model of communication aids in the study of how the media functions. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics (Figure 1). Westley-MacLean Model of Communication Westley, B., and M. MacLean. 1957. “A conseptual Model for Communication Research.” Journalism Quarterly, 34:31-38 4 The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics Westley and MacLean (1955) posit four different participating parties involved in media communications. The parties are of A (advocacy role), C (communication), B (receiver), X (objects of orientation), and f (feedback). X’s represent “objects of orientation” which includes; events, objects, ideas, and people. The Xs are within the sensory of A, B, and C. The A represents the advocacy roles and observes the Xs and then transmits purposeful messages about its findings through media. C represents the communicator responsible for channel roles that are received by B. An example of this would be television channels, websites, newspapers, etc. C also functions as a “gatekeeper” which selects information from Xs and A, and strives to satisfy B’s desire of information. C then chooses what outlet/medium is appropriate for obtaining information to B roles. Now with the Internet and faster means of communication, C is able to receive information from several Xs. However, creating meaning is difficult out of bias/raw information from the Xs; therefore, A is still necessary for more accurate perception, according to Westley and MacLean (1957). . The Westley-MacLean model allows messages to be purposive (with the intent of modifying B’s perception of X) or non purposive (without any intent on the part of the communicator to influence B) (Severin and Tankard, p. 61, 2001). With B being perceived as the public or individual groups, they need information about The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 6 their environment to help gratify self-satisfaction and help solve problems (Severin, Tankard, p. 63 2001). The model also provides feedback (f) from the receiver (B) to the communicator (C) as well as from the communicator (C) back to the advocate (A). Without this connection of feedback from the different consumers there would be a lack in information development and in construction information selection. This model is important in the understanding of how consumers take in news media and how the different channels, orientations, and advocates can affect consumer perceptions. This mass communications model aids in understanding how the different theories of mass media effects could effect economic development. MEDIA EFFECTS The effects of mass media are theoretically applicable to the fluctuations in economic development and are either direct or indirect. McGuire noted several of the most commonly mentioned intended media effects are; (a) the effects of advertising on purchasing, (b) the effects of political campaigns on voting, (c) the effects of public service announcements (PSAs) on personal behavior and social improvement, (d) the effects of media ritual on social control (McGuire, 1989). McGuire also pointed out the most commonly mentioned unintended media effects; (a) emotional behavior, (b) the impact of media images on the social construction of reality, (c) the effects of media bias on stereotyping, and (d) how media forms affect cognitive activity and style (McGuire, 1989). In addition to these media effects, McGuire’s partner, McQuail, summarizes that the main streams of effects research of other areas of media effects are; (a) knowledge gain and distribution throughout society, (b) diffusion of innovations, (c) The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics socialization to societal norms, and (d) institution and cultural adaptations and changes (McQuail 1972). A more in-depth analysis will be explored on specific media effects in this body of work. Media Agenda Setting The concept of agenda setting set by the media is a likely factor that can influence economic development. The agenda-setting function of the media refers to the media’s capability, through repeated news coverage, of raising the importance of an issue in the public’s mind (Severin, Tankard pg. 219). McCombs and Shaw reported the first systematic study of agenda-setting hypothesis in 1972. Findings in McCombs and Shaw’s “Chapel Hill Study” supported that mediaagenda setting can influence political campaigns (1972). Voter perception of a particular campaign platform was shaped based on what the media choose to emphasis on. McCombs and Shaw’s data suggested that a strong relationship between the emphasis placed on different campaign issues by the media and the judgments of voters are to the salience and importance of various campaign topics (1972). A precursor to McCombs and Shaw’s hypothesis suggests that what people will think the facts are, and what most people will regard as the way problems are to be dealt with is portrayed through the media (Norton Long, p. 260 1958). Also, mass media forces attention to certain issues and are constantly presenting objects suggesting what individuals in the mass should think about, know about, have feelings about (Kurt, Gladys Engle Lang p. 232 1959). The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 8 Concepts that the media reported on were economic policy of the different campaigns (McCombs and Shaw 1972). These reports could influence consumer confidence. The level of consumer confidence augurs consumer spending— and thus the future trajectory of the economy— and it affects a variety of political behavior such as election outcomes, macropartisanship (Erikson, MacKuen, and Stimson 2002), presidential approval (MacKuen, Erikson, and Stimson 1992, public policy mood (Durr, 1993), congressional approval (Durr, Gilmour, and Wolbrecht 1997), and trust in government (Chanley, Rudolph, and Rahn 2000). Additional experiments have been conducted to learn more about the effects of media agenda setting. Media agenda setting determines the criteria by which an issue will be evaluated (Iyengar, Kinder, Peters, 1982). This concept is known as priming. Priming is the process in which media attends to particular issues and not others and thereby alter the standards by which people evaluate and act on an issue (Severin, Tankard p 226). The concept of priming builds on the idea that mass media does have the power to build agendas outside of its own. Therefore, the media acts as a director, actor, and consumer of it’s own product. The application of agenda setting and it’s influence on economic development can be seen in the case study of news coverage on women in the 1996 Olympic games and how the economy had a slight dip. Newspaper coverage of the 1996 Olympic games primarily were of women due to the addition of two women’s events debuted which was soccer and softball, along with women’s mountain biking and beach volleyball. The media emphasized on women’s progress. Women also The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics were recognized as an important television audience. NBC, the official U.S. Olympic television network, sought to deliver on promised rating to advertisers by attracting the largest possible audience and women were the target (Kinnick, 1998). Women decided to follow the Olympic games by watching television rather than going out and shopping suggests Kinnick. This in turn caused a brief moment of loss in the month of August in the gross retails sales on a national level. Little growth in economic activity was seen and some economist believe that the rise in women viewership of the Olympics set off the slowing of gross retail sales on a national level (Kinnick, 1998). Cultivation theory, used in mass media studies, is a concept that explains how people’s perceptions, attitudes, and values change from consumption of media. Exposure to the same messages that debut in the mass media produces what researchers refer to cultivation, or the teaching of a common worldview, common roles, and common values (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, and Signorielli, p. 14 1980). Thus, Media can have a negative impact upon cognitive thinking. Psychological literature supplements the cultivation theory by suggesting that unfavorable information has a greater impact on impression than does favorable information, across a wide variety of situations (e.g., Ronis and Lipinski 1985; Singh and Teoh 2000; Van der Pligt and Eiser 1980; Vonk 1993, 1996). Stuart N. Soroka’s (2006) research in media’s effect on economics suggests that there exists an “asymmetric responses to bad and good economic information”. Research in economics posits a prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Prospect theory is a choice under uncertainty, which contains a feature The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 10 called loss aversion. People react more fervently towards a loss in utility than they do towards a gain of equal magnitude (Soroka, 2006). This individual-level loss adverse behavior is evident in macroeconomic dynamics: consumption tends to drop more when the economy contracts than rise when the economy expands (Bowman, Minehart, and Rabin 1999). Examples in media suggest that overemphasizing the prevalence of violent crime (e.g., Altheide 1997; Davie and Lee 1995; Smith 1984), and events involving conflict or crisis receive a greater degree of media attention (Bagdikian 1987; Herman and Chomsky 1988; Parachos 1988; Patterson 1997; Shoemaker, Danielian, and Brendlinger 1991). Most relevant to the current analysis, U.S. networks regularly give more coverage to bad economic trends than to good economic trends (Harrington 1989). The prominence of negative media coverage may be driven by the same individual-level theories such as media agenda setting, priming, and framing. Journalists are individuals, writing articles to appeal to other individuals and thus regard negative information as more important, not just based on their own interests, but also on the interests of their news consuming audience (Soroka, 2006). There is however, an alternative explanation for the prominence of negative news. It may be that media outlets’ emphasis on negative news reflects one of the principle institutional functions in democracy: holding current Governments (and companies, and indeed some individuals) accountable (Carlyle 1841). Therefore, media is a surveillance that mainly involves identifying problems and at times over The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics emphasizes negative information. But some scholars think it is the media’s job to do so (David Lyon, p. 21, 2007). Surveillance of the media includes economy facts, stock market reports and the overall well being of a nation (Severin and Tankard, p. 321, 2006). Surveillance function can cause several dysfunctions such as panic due to the overemphasis of issues facing a society. Lazarsfeld and Merton (1948/1960) noted that “narcotizing” dysfunction when individuals fall into a state of apathy or passivity as a result of too much information to assimilate may leave many audience members with little perspective of what is normal. Studies of media effects on economic fluctuations propose that the 1990 recession, in popular belief, was widely spread by the press’s effect on people’s pessimism of the general economy (Marcelle Chauvet and Jang-Ting Guo, 2003). Negative reports on the national economy led to a fall in consumer confidence (Marcelle Chauvet and Jang-Ting Guo, 2003).1 In particular, the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meeting in December 1990 pointed to consumer sentiment as one of the principal contributing factors for this recession. Blanchard (1993) and Hall (1993) both attribute the 1990 recession to a significant drop in consumption, and speculate that consumer sentiment may have had something to do with it. Findings conducted by Chauvet and Guo (2003) pointed out that consumption growth did switch to a low-growth state at the beginning of the 1989 1 For example, The New York Times on April 3, 1991, reported a quote by Roger Brinner, director of research at DRI/McGraw-Hill, that “If consumers hadn’t panicked, there wouldn’t have been a recession.” In addition, the lead story in The Wall Street Journal on November 4, 1991, was entitled “Economy in the U.S. Isn’t Nearly as Sour as the Country’s Mood. But Pessimism Could Become Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Further Stalling Recover. Can Attitude Be Everything?” The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 12 slowing of the economy (Figure 2). Consumer confidence also fell during the slowing, as observed in all the previous low-growth phases and recessions (f1) (Chauvet and Guo, 2003). However, the probabilities of consumer pessimism based on non-fundamentals rose only in July 1990, which coincided with the onset of this recession (Figure2). The same pattern was observed for growth in personal income, manufacturing trade and sales, and employment, whose falls coincided with the beginning of this recession. Therefore, consumers’ pessimism did not seem to be a source of this recession (Chauvet and Guo, 2003). However Chauvet and Guo (2003) notes that consumers’ pessimism may have been an important factor in intensifying and extending the 1989-1992 economic slowdown. The figures created by Chauvet and Guo (2003) reveal that low consumption growth phase lagged consumers’ pessimism, and lasted until the end of the sample in 1995. Thus, the unprecedented extended slowdown could have been a reflection of consumers’ attitudes toward the economy after the official end of the 1990 economic recession (Chauvet and Guo, 2003). Chauvet and Guo (2003) proposed at the end of their research that U.S. recessions and slowdowns could have been responses not to shifts in economic fundamentals, but to agents’ self-fulfilling pessimism. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics (Figure 2). (f1-f4 clockwise starting top left) The 1990 recession: Probabilities of consumers’ and investors’ pessimism, low consumption and investment growth states, investment growth, 3-month T-Bill rate, growth rates of employment, personal income, and sales—NBER recessions (shaded areas) and slowdowns (- - -). Marcelle Chauvet . SUNSPOTS, ANIMAL SPIRITS, AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS. Macroeconomic Dynamics, Volume 7, Number 1 (February 2003), pp. 140-169, http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=J8D8D5YBVKD44TTPFUQ6 The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 14 Self-fulfilling pessimism is the result from news refraction hypothesis suggested by McLeod and associates (1995). Their hypothesis suggests that local content of news media exposure could have a strong influence on perceptions of issues and the “closeness of home”. Therefore, viewer’s doubts suppress the urge for action, and a reclusive approach is taken towards issues (McLeod et al., 1995). A study of the media’s impact on the Mississippi Gulf Coast economy after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill was conducted to support the theory that media can potentially impact an economy. The oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, which began after the Deepwater Horizon rig explosion on April 20th and continued to leak for another three months was a challenging event for news media to cover. Unlike most catastrophes, which tend to break quickly and subside almost as fast, the spill was a slow-motion disaster that demanded constant vigilance and sustained reporting (journalism.org). Also the media had to learn how to report on the oil spill by using NOAA (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) maps and by consulting scientist and researchers who were part of the response team for BP. The story on a national level consisted of three competing story lines-the role of BP, the Obama Administration, and the events in the Gulf region. The coverage of the disastrous saga along affected coastal states was in-depth. Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida pan handle was bombarded with journalists literally waiting on the beaches and headlining articles about how the oil was an economic, ecological, and political Armageddon. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics To evaluate the coverage, PEJ (Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism) studied approximately 2,866 stories about the oil spill produced from April 20 to July 28-from the day that the Deepwater Horizon exploded to the day the BP CEO Tony Hayard’s departure was announced. From that time, the oil spill was by far the dominant story in mainstream news media in the 100-day period. It accounted for 22% of the newshole and in the 14 full weeks included in this study, the disaster finished amount the top three weekly stories 14 times (PEJ, 2010). It registered as the No. 1 story in nine of those weeks (PEJ, 2010). Figure 3 represents the percent of newshole coverage. (Figure 3) http://www.journalism.org/analysis_report/100_days_gushing_oil The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 16 Case Study A study was conducted of the primary local paper of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The Sun Herald ran articles related to the oil spill on a daily since April 22, 2010 until the end of the research on August 31, 2010. In addition to counting how many articles appeared in the Sun Herald relating to the Oil spill, a word count of oil/spill was also conducted (Figure 4). In addition, two other newspapers that are exposed to local residents were studied. Article counts were conducted on the New Orleans Times-Picayune and the Mobile Press-Register (Figure 4). These two papers also contained daily articles of the oil spill. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics (Figure 4) Collected newspaper data Newspaper Source April 24 May 301 June 358 July 301 August 121 Press-Register 33 329 337 284 272 TimesPicayune 12 206 234 181 52 120 1517 2430 1406 567 Sun Herald Word Count Sun Herald Source: Hard copies of each paper The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 18 Economic data of Gross retail sales and unemployment rate of the three coastal counties; Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson, was collected. The months of May, June, July, and September revealed an increase in unemployment rate (Mississippi Department of Employment Security, 2010), (Figure 5). The month of August reported a decrease in the unemployment rate (Figure 6), which related to the increase in BP volunteers for the month of July when the oil came ashore more abundantly. Also the newspaper reports less on the oil spill in the months of July and August. If all newspaper articles were held constant from the previous month, September’s increase in unemployment though, would prove that little relation exists between media and economic impact (Figure 7). The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics (Figure 5) Collected Data of Article Count/WordCount, Retail Sales% Change 09-10, Unemployment % Change 09-10 Source: Hard copy of newspaper/Unemployment Rates: http://www.mdes.ms.gov/Home/docs/LMI/Publications/Labor%20Market%20Data/labormarketdata.pdf Mississippi Gross Retail Sales: Mississippi Department of Revenue: http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_1010.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0910.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0810.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0710.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0610.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0510.pdf, Month May June July August News Paper Sun Herald Press-Register TimesPicayune Article Count 301 329 Sun Herald Press-Register TimesPicayune 358 337 Sun Herald Press-Register TimesPicayune 301 284 Sun Herald Press-Register TimesPicayune 121 272 Word 1517 206 2430 234 1406 181 52 567 County Hancock Harrison 2009-2010 Retail Sales % Change (-)6.12 (-)7.46 2009-2010 Unemployment % Change 1.6 2.3 Jackson (-)8.04 2.4 Hancock Harrison (-)14.69 (-)6.95 .9 1.4 Jackson (-)7.41 1.3 Hancock Harrison (-)14.69 (-)10.54 1.2 1.2 Jackson (-)3.73 1.2 Hancock Harrison (-)18.16 1.00 (-)0.3 (-)0.3 Jackson (-)2.38 (-)0.4 The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 20 (Figure 7) Mississippi State Tax Commission Two-Year Comparison of Gross Retail Sales 2009-2010 May Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County June Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County July Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County 2009 $663,508,863.87 $4,049,297,147.04 $1,880,907,665.18 2010 $622,871,688.98 $3,747,045,158.16 $1,729,726,459.39 Difference ($40,637,174.89) ($302,251,988) ($151,181,205.79) (-)6.12% (-)7.46% (-)8.04 $720,090,435.01 &4,392,627,311.30 $2,044,062,723.58 $675,428,513.22 $4,087,141,874.45 $1,892,597,535.49 ($44,661,921.79) ($305,485,436.85) ($151,465,188.09) (-)6.20% (-)6.95% (-)7.41% $71,296,099 $379,195,437 %185,656,947 $60,822,315 $419,153,048 %192,584,360 ($10,473,784) ($39,957,611) ($6,927,413) (-)14.69% (-)10.54% (-)3.73% Source: Mississippi Gross Retail Sales: Mississippi Department of Revenue: http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_1010.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0910.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0810.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0710.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0610.pdf, http://www.dor.ms.gov/docs/stats_172summary_0510.pdf % The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics August Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County September Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County October Hancock County Harrison County Jackson County $140,907,979 $751,422,627 $339,872,736 $115,323,203 $758,940,117 $331,777,981 ($25,584,776) $7,517,490 ($8,094,755) (-)18.16% 1.00% (-)2.38 $165,330,045 $1,073,863,967 $461,196,959 $198,709,060 $1,101,365,019 $484,196,969 ($33,379,015) ($27,501,052) ($23,000,010) (-)16.80% (-)2.50% (-)4,75% $213,678,199 $1,398,080,157 $605,895,473 $254,912,577 $1,425,405,084 $649,069,627 ($41,234,378) ($27,324,927) ($43,174,154) (-)16.18% (-)1.92% (-)6.65% (Figure 6) Unemployment Rate by County Mississippi Department of Employment Security May Hancock Harrison Jackson June Hancock Harrison Jackson July Hancock Harrison Jackson August Hancock Harrison Jackson September Hancock Harrison Jackson 2009 2010 8.0% 7.2% 7.8% 9.6 9.5% 10.2% % Change 1.6 2.3 2.4 8.3% 7.8% 8.4% 9.2% 9.2% 9.7% 0.9 1.4 1.3 8.4% 8.1% 8.7% 9.6% 9.3% 9.9% 1.2 1.2 1.2 8.0% 7.7% 8.3% 7.7% 7.2% 7.9% (-)0.3 (-)0.3 (-)0.4 7.9% 7.5% 8.4% 8.7% 8.1% 8.9% 0.8 0.6 0.5 The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 22 A survey was conducted asking 100 coastal residents: What is the greatest threat from the oil spill? 78% wrote that the greatest threat was towards the local economy (figure 8). A pole conducted in October revealed that: 42% believed the media coverage of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill was a key factor the slowing of the local economy while 37% believed the national recession was a possibility, 16% blamed it on Hurricane Katrina, and 5% responded: no opinion (figure 9). The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics (Figure 8) (Figure 9) The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 24 “Dead sea turtles wash ashore,” claimed the Sun Herald on May 2, 2010. Journalist would write articles about the turtles even though their cause of death was not related to the oil spill, which was proved by marine biologists. These types of articles began to frequently appear in the local papers such as the Times Picayune of New Orleans, LA, the Pres-Register of Mobile, AL, and the Sun Herald of Gulfport, MS. These three papers were of particular interest in this case study because they are the most consumed papers along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The media agenda setting effects began to naturally set in as the oil continued to gush. Story after story from journalist trying to outdo each other has filled the wires for years to come of the effects of the oil spill. There was an overreporting of significant but unusual events. This was an issue in the Santa The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics Barbara oil spill, which was significant but received exaggerated coverage because of it’s unusualness and because people enjoy the sensationalism (Severin, Tankard p 232 2001). Observations suggest the media’s agenda emphasized on gushing oil, dying wildlife, tainted seafood, and oiled beaches (Sun Herald appendix) the media did not specifically state that small regions affected. Even though the media was clear in portraying which areas were being impacted, the content was correct. The effects of the media on a national level could have possibly impacted people pessimisms and following with possible economic slowdown suggested by (Chauvet, Guo 2003), economy (figure 9). As the surge of media reports on the oil spill flooded the mass media, economic impact along the Mississippi Gulf Coast experienced little significant growth. Overall, the oil spill created job losses and also crushed the fishing industry, which had a ripple effect that reached restaurant nationwide. At the same time though, BP created temporary jobs along the gulf states and also occupied hundreds of hotel rooms. These factors are significant in contributing towards the economic data researched. Adam Sacks, managing director of Oxford Economics USA mentioned that “History and current trends indicate a potential $22.7 billion economic loss to the travel economics of the Gulf Coast states over the next three years could be possible” (Sun Herald 07/24/2010). Sacks continues, “One of the most costeffective ways to mitigate these damages is to immediately fund strategic marketing to counter misperceptions and encourage travel to the region” (Sun Herald The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 26 07/24/2010). Misperception created by the media is a factor that Sacks mentions in his consulting towards the Gulf Coast tourism sector. Conclusion: Theories support the idea that mass media has significant economic impact. Media theories such as media agenda setting, priming, framing, and cultural theory support the concept of how media can impact an economy, however little research has been conducted on this subject. Economic research supports the idea that sentiments of the consumer can be affected by media content and therefore could lead to fluctuations in the economy. Research posited by Chauvet and Guo (2003), support the idea that an economic slowdown is impacted by agents’ self-fulfilling pessimism. Studies such as Soroka’s work (2006) strengthens the argument that; public responses to negative economic information such as the oil spill, are much greater than are public responses towards positive information. This suggests that the media’s portrayal of the oil spill could have caused more harm than good on the perception of the local economies. Limitations: The case study of how media’s coverage of Deepwater Horizon and the impact on the Mississippi Gulf Coast economy is limited in many ways. More economic data such as sales tax, inflation, and direct tax losses would aid in further research of how the effects of media relate to the economy’s slump. Also, data starting pre Katrina would an important addition to real the fluctuations in the economic cycle of the three coastal counties. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics Additional newspaper research is necessary in the future of this research. The reflection of the articles, negative or positive, could support the pole data that was conducted as well. Time constraint was the greatest obstacle in research. Greater evidence from next year’s economic data would be of better support that what is available now. Quantitative research now is rather premature at this moment. The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 28 References: Altheide, David L. 1997. “The News Media, the Problem Frame, and the Production of Fear.” Sociological Quarterly 38 (4): 647-68. Bagdikain, Ben. 1987. The Media Monopoly. 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press. Blanchard, O.J. (1993) What caused the last recession? Consumption and the recession of 1990-1991. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 83, 270-274. Bowman, David, Deborah Minehart, and matthew Rabin. 1999. “Loss Aversion in Consumption-Saving Model.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 38 (2): 155-78. Carlyle, T. 1841. Heroes: Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History. New York: Charles Scibner and Sons. Chanley, Virginina A., Thomas J. Rudolph, and Wendy M. Rahn. 2000. “The Origins and Consequences of Public Trust in Governemnt.” Public Opinoin Quarterly 64(3): 239-56. Chauvet, Marcell. and Guo, Jang-Ting. 2003. “Sunspots, Animal Spirits, and Economic Fluctuations.” Macroeconomic Dynamics. 7:140-169. Davie, William R., and Jung sook Lee. 1995. “Sex, Violence, and Consonance/Differentiation: An Analysis of Local TV News Vlaues.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 72 (1): 128-38. Durr Robert H. 1993. “What Moves Policy Sentiment?” American Polcicial Science Review 87(1):158-70. Durr, Robert H., John B. Gilmour, and Christina Wolbrecht. 1997. “Explaining Congresional Approval.” American Journal of Poitical Science 41(1):175-207. Erikson, Robert S., Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson. 2002. The Macro Polity. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gerbner, G., L. Gross, M. Morgan, and N. Signorielli. 1980. “The “Mainstreaming” of America.” Violence profile no.11 Journal of Communication, 30(3): 10-29. Hall, R.E. (1993) Macro theory and the Recession fo 1990-1991. American Economic Review Papers and proceedings 83, 275-279. Harrington, David E. 1989. “Economic News on Television: The Determinants of Coverage.” Public Opinion Quarterly 53 (1): 566-74. Herman, Edward S., and noam Chomsky. 1988. Manufacturing Consent: The polical Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books. Iyengar, Shanto, and Donald R. Kinder. 1987. News that Matters. Chicago: Chicago The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics University Press. Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk.” Econometrica 47 (2): 263-92. Kinnick, Katherine. 1998. “Gender Bias in Newspaper Profiles of 1996 Olympic Athletes: A Content Analysis of Major Dailies.” Women’s studies in Communication. 21: 156-59. Lank, K. and G.E. Lang. 1959. The Mass media and Voting. In E. Burdick and A. J. Brodbeck, eds. American Voting Behavior. Pp. 217-235. Glencoe, III.:Free Press. Lazarsfeld, P., and R. Merton (1948/1960). Mass Communication, Popular Taste, and Organized Social Action. In L. Bryson, ed. (1948), The Communication of Ideas. New York: Institute for Religious and Social Studies. Repreinted in W. Schramm, ed. (1960), Mas Communications. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Long, N.E. 1958. The Local Community as an Ecology of Games. American Journal of Socialogy. 64:251-261. Lyon, David. 2007. Surveillance Studies An Overview. 1st ed. Malden, MA: Polity Press. MacKuen, Michael B., Robert S. Erikso, and James A. Stimson. 1992. “Peasants or Bankers? The American Electorate and the U.S. Economy.” American Politcial Science Review 86(3):597-611. McCombs, M. E. and D.L. Shaw. 1972. The Agenda-setting Function of Mass Meida. Public Opinion Quarterly. 36:176-187. McGuire, W.J. 1989. “Theoretical Foundations of Campaigns.” In R.E. Rice and C.K. Atkin, eds. Public Communication Campaigns. 2nd ed. Pp.43-65. Newbury Park. Calif.:Sage McLeod, J.M., K. Daily, W.Eveland, Z. Guo, K. Culver, D.Kurpius, P.Moy, E. Horowitz, and M. Zhong (1995). The Synthetic Crisis: Meida Influences on Perceptions of Crime. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Communication Theory and Methodology Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Washinton, D.C., August. McQuail, D., J.G. Blumler, and J.R. Brown. 1972. “The Television Audience: A revised Perspective. In D. McQuail, ed., Sociology of Mass Communications, pp. 135165. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin. Paraschos, Manny. 1988. “News Coverage of Cyprus: A Case Study in Press The Mass Media and its Impact on Economics 30 treatment of Foreign Policy Issues.” Journal of Political and Military Sociology 16 (2): 201-13. Patterson, Thomas E. 1997. “The News Meida: An Effective Policial Actor?’ Political Communciation 14 (4):445-55. Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism. 2010. 100 Dys of Gushing Oil. August 25, 2010. http://www.journalism.org/analysis_report/100_days_gushing_oil Ronis, David L., and Edmund R. Lipinski. 1985. “Value and Uncertainty as Weighting Factor in Impression Formation.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 21 (1): 47-60. Severn, Wener, and Tankard, James. 2001. Communication Theories: Origins, Methods, and Uses in the Mass Media. 5th ed: Longman. Shoemaker, Pamela, J., Lucig H. danielian, and Nancy Brendlinger. 1991. “Deviant Acts, Risky Business and U.S. Interests: the newsworthiness of World Events.” Journalism Quarterly 68 (4): 781-95. Singh, R., and J.B.P Teoh. 2000. “Impression Formation from Intellectual and Social Traits: Evidence for Behavioural Adaptation and Cognitive Processing.” British Journal of Social Sychology 39 (4): 537-54. Smith, Susan J. 1984. “Crime in the News.” British Journal of Criminology 24 (3): 289-95. Soroka, Stuart N. 2006. “Good News and Bad News: Asymmetric Responses to Economic Information.” The Journal of Politics. 68(2): 372-385. Van Der Pligt, Joop, and J. Richard Eiser. 1980. “Negativity and Descriptive Extremity in Impression Formation.” European Jouranl of Social Psychology 10 (4): 415-19. Vonk, Roos. 1996. “Negativity and Potency Effects in Impression Formaiton.” European Journal of Social Psychology 26 (6): 851-65. Westley, B., and M. MacLean. 1957. “A conseptual Model for Communication Research.” Journalism Quarterly, 34:31-38 http://www.dor.ms.gov/; http://www.mdes.ms.gov/Home/index.html