PARENTS’ GUIDE TO A HEALTHY START

PRESCHOOL AGE

A Project

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Child Development

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Child Development

(Theory and Research)

by

Silvia Cane-Galvis

SPRING

2012

© 2012

Silvia Cane-Galvis

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

PARENTS’ GUIDE TO A HEALTHY START

PRESCHOOL AGE

A Project

by

Silvia Cane-Galvis

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Ana Garcia-Nevarez

__________________________________, Second Reader

Lynda Stone

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Silvia Cane-Galvis

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format

manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for

the project.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Kristen Alexander

Department of Child Development

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

PARENTS’ GUIDE TO A HEALTHY START

PRESCHOOL AGE

by

Silvia Cane-Galvis

Statement of Problem

Societal changes in living demographics, changes in school system regulations, and

an increase in the amount and availability of screen-based entertainment have

significantly decreased the amount of time and experiences children engage in outdoor

play (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). The literature identified a

critical importance of a healthy diet is synergistic with outdoor play to have a more

effective impact on healthy development. Therefore, the need to inform parents, teachers

and society about the advantages of healthy eating and involvement in outdoor activities

is crucial. The purpose of this project is to create a clear, concise, easy to implement

guide for parents in the Sacramento County that explains the benefits of outdoor

activities. The “Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start” links these benefits with several

developmental domains (cognitive, socio-emotional and language) and presents the

negative effects of sedentary life styles. It also includes healthy eating habits, outdoor

activities, and local resources. While there are other publications that offer some of this

v

information, there are no resources currently available to offer parents a well-rounded

informative guide.

Sources of Data

An extensive review of the literature was conducted to identify empirical and

theoretical studies, as well as books and online resources about outdoor play in early

childhood. The literature review includes the following topics: the benefits of outdoor

play, changes in living demographics and school systems, developmental consequences

of sedentary live styles, healthy eating habits, and parents’ role in outdoor play. After

completion of the literature review, the researcher developed the guide that included all

the above. Furthermore, the researcher included a section on gardening, outdoor play

activities, and local resources available to the public in the Sacramento region.

Conclusions Reached

There is a wealth of studies about benefits of outdoor play and negative effects of

sedentary life styles for children’s healthy development. There are also publications and

many local resources available for families who are in need of this information. However,

none of these publications cover all of the factors found by the literature for families to

understand the importance of outdoor activities in a concise and easy to read format. The

“Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start” provides parents with information and hands-on

activities. In addition, it offers information about community resources that can help

vi

families learn more and become connected with many other activities and resources. The

guide allows parents’ to get all the information in one handbook and become aware of

easy ways to help their children have a healthy start that will carry on into adulthood.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Ana Garcia-Nevarez

_______________________

Date

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express the deepest appreciation and gratitude to my committee

chair, Professor Garcia-Nevarez who supported me through this process. Without her

guidance and her persistent help, this project would not have been possible.

I would like to thank my committee member, Professor Stone, who demonstrated

and modeled the importance of good writing skills and was always a source of

knowledge. I learned so much and will forever have with me the examples and skills I

gained during this process.

To my mother, I would like to say that her support, love and life long caring are

what made any of this possible. I love you mom and thank you for always being there for

me.

In addition, a huge thank to my wonderful husband Michael Cane, who helped me

find in myself the deep love I now have for nature. He has been a true example of how

love for nature has a positive impact in quality of life. He has taught me so much about

enjoying nature, the importance of conservation biology, and how essential it is to expose

children to nature, instead of buying them pre-made toys. I feel so blessed to have met

you and to be able to share this fun trip called life with you.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. viii

List of Figures ...........................................................................................................................xi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION …………….. ……………………………………………………….. 1

Statement of the Problem ............................................................................................. 2

Purpose of the Project .................................................................................................. 5

Significance of the Project ........................................................................................... 6

Methodology………………………………………………………………………… 7

Definition of Terms ...……………………………………………………………….. 10

Limitations of the Project …………………………………………………………… 12

Organization of the Project………………………………………………………….. 13

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................. 15

Demographic areas .................................................................................................... 15

School changes .......................................................................................................... 17

Benefits of outdoor play ………………………………………………………….... 21

Play deprivation ……………………………………………………………………. 24

Healthy diets ……………………………………………………………………….. 26

Parents’ role ………………………………………………………………………… 28

Theoretical Framework …………………………………………………………….. 31

Cognitive Development Theory..................................................................... 31

Language Development Theory..................................................................... 33

Socio-Emotional Development Theory ……………………………………..34

Attention Restoration Theory………………………………………………...35

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………….. 36

3. METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 38

Design of the Project ………………………………………………………………. 37

Online and book searches ............................................................................ 41

Procedures .................................................................................................................. 44

ix

4. DISCUSSION, RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS ……………………. 48

Discussion …………………………………………………………………………….48

Limitations of the Project……………………………………………………………..51

Recommendations ……………………………………………………………………52

Conclusion... ………………………………………………………………………….53

Appendix A. Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start Preschool Age ..................................... ….. 55

References ............................................................................................................................... 86

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1. Percentage of Population Living in Urban Areas……………………………………15

xi

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Play “… is the purest most spiritual activity of a man at this stage [childhood],

and at the same time, typical of human life as a whole, of the inner hidden natural life in

man and all things. It gives, therefore, joy, freedom, contentment, inner and outer rest,

peace with the world.”

Friedrich Frobel (1887, p. 55).

In recent years there has been an increased interest from child development

professionals to research the benefits of outdoor play for a child’s healthy development.

This research interest has arisen in part due to the realization that our society has gone

through many profound changes in the way we live over the past century. These changes

have increased researchers’ interest in finding out how children’s development is being

affected. Amongst the changes, we can find that many families have decreased the

amount of outdoor time experienced in part due to a shift to living in suburban areas.

Also, there has been a recent emphasis on state and federally regulated academics, and an

increase in screen forms of entertainment, which encompasses TV, computers and video

games.

2

Research has found that children who are encouraged to spend time playing

outdoors are more likely to develop an array of cognitive, language, and socio-emotional

skills necessary to be successful in schooling and life in general than sedentary children.

For example, children with higher rates of outdoor play use their imagination more and

develop greater and more complex language skills (Fisher, 1992; Carson, 1998), long

term positive attitudes towards science, (Harland & Rivkin, 2000) and are able to engage

in more complex levels of motor skills, such as sustained balance and better climbing

skills.

Furthermore, outdoor play has been associated with better social-emotional skills

needed to build relationships with peers. Examples of building relationships with peers

include, following cues, learning about others’ feelings, and being able to express

emotions and needs (Erickson, 1963 & Piaget, 1962). These social emotional skills are

important as children engage in play with others and have to negotiate game rules.

Statement of the Problem

The Census Bureau (2001) found that there has been a rapid change in living

situation for families in the United Stated. In 1850, ninety percent of the population in the

United States lived in rural areas, which rapidly declined to a mere ten percent by 1990.

This change has limited children’s opportunities for free, outdoor play due in part to a

reduced sense of safety by people who live in highly developed cities, including a fear of

3

traffic (Hillman, 2000). In addition, studies have found that children who live in rural

areas are more physically active than children who live in suburban areas (Dollman,

Maher, Olds, & Ridley, 2012). The aforementioned might possibly be explained by the

higher percentage of indoor and outdoor space available for rural families. In addition,

many suburban areas are built without “connectivity” in mind, which limits an

individual’s mobility and access to outdoor areas and places where active play usually

occurs. Connectivity allows families to go from their home to other parts of their

neighborhood without having to take a long, or heavily trafficked route (Committee on

Environmental Health, 2009). The lack of connectivity in suburban areas forces families

to drive places and limits the time families have to spend in outdoor play.

Another change found by research that affects children’s time outdoors is a

change in California’s school system due to regulations set by the “No Child Left Behind

Act” (NCLB) of 2001 (Hendrie, 2005). This law puts an increased emphasis on reading

and math in an effort to close the achievement gap for low-income students (US

Department of Education, 2001). NCLB has inadvertently put a damper on the amount of

time children have to spend outdoors. The increase in testing and assessments required

has limited the amount of time left available to spend in free play (Persellin, 2007)

despite findings that free play benefits academic performance by encouraging creativity

(Epstein,2008), exploration, and experimentation (Fasko, 2001).

In addition, there has been an increase in the variety and amount of time in

screen-based entertainment, which includes TV, videogames, cellphones, and other hand

4

held devices that young children use on a daily basis. Funk, Brouwer, Curtiss, and

McBroom, (2009) found that the majority of preschool children in their study had 2 to12

hours of TV viewing per week, which is a higher exposure than the American

Association of Pediatricians (AAP) recommends. AAP (2011) recommends no TV

viewing for children under two years old and instead encourages parents to find activities

that promote language development, socialization, imagination, and physical activity

such as unstructured play, which can help children to think creatively, problem-solve and

improve their motor skills.

Piaget (1962) found that children in the preoperational stage of cognitive

development benefit from active outdoor play as they learn through active involvement

with the environment around them. However, research has found that parents do not

share the same belief that play is essential for a child’s healthy development. Instead,

parents separate play from learning and do not see the relationship of how play facilitates

learning via hands-on experimentation (Rothlein & Brett, 1987).

Societal changes and parental lack of understanding of outdoor play benefits have

created a sense of urgency on the part of child development professionals, pediatricians

and nutritionists. Since parents have such a powerful impact on their children’s

development it is essential for parents to comprehend the benefits of outdoor play and

good dietary habits for healthy development. This project’s goal is to create a guide for

parents called “Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start” with key information about benefits of

outdoor play, how to effectively and easily add outdoor play to their daily routines, local

5

resources for family outdoor activities and information about how specific outdoor

activities enhance healthy cognitive, social-emotional, and language development for

their child. A review of the research literature identified the critical importance of a

healthy diet and healthy eating habits in early childhood. The combination of outdoor

play with healthy eating has a synergistic effect on healthy development. Therefore the

Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start includes information from the Center for Disease

Control (CDC), United State Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of Health

and Human Services (HHS) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on the

importance of a balanced, healthy diet. Since this information discusses increased

consumption of vegetables and fruit, the Guide has directions on how to build a raisedbed garden and the locations of Farmer’s Markets in Sacramento County.

Purpose of the Project

The purpose of this project is to create a clear, concise, easy to implement guide

for parents in the Sacramento area that explains the benefits of outdoor activities for a

child’s development. The research literature includes many findings on the negative

effects that sedentary lifestyles can have on children’s development, thus this cautionary

information is included in the Guide as well. A review of the literature revealed that

healthy eating habits in conjunction with outdoor active experiences have a more

significant, positive influence on children’s healthy developmental outcomes than either

6

outdoor play or healthy eating, alone. Hence, the guide for parents includes information

on the benefits of both outdoor play and healthy eating habits. It offers information about

local community resources that support families’ outdoor experiences and healthy eating

habits and activities that help children engage in and enjoy outdoor play. In the activities

section of the guide, there are vignettes for social-emotional, cognitive and language

development that promote parent’s better understanding of how each activity enhances

development. These specific activities were selected and then included to offer

possibilities to parents of ways in which outdoor play can be added to their daily lives

and how this directly benefits their children

Significance of the Project

The combination of families increasing their focus on academics and their

growing and pervasive use of technology and media makes it critical for parents to

become more informed about the benefits of outdoor activity as part of a more balanced

educational approach. Moreover, the lack of such approaches has resulted in families

with little to no awareness of how to include the outdoors as a regular part of their daily

lives (Louv, 2008). Hence, it is the researcher’s goal that this guide will serve as the basis

for parents to start including the outdoors in their family’s life, learning to enjoy it and

making active outdoor play as part of their daily routine.

7

The guide for parents developed by the researcher in this project, Parent’s Guide to

a Healthy Start, is significant because it provides parents of preschool-age children with

the tools and resources to engage children in outdoor play, and counteract tendencies

toward sedentary life styles. Many parents do not realize that outdoor play not only

counteracts sedentary life styles but also contributes in fundamental ways to children’s

competent engagement in the world. For example, outdoor activity benefits cognitive

development by allowing children to concentrate better after contact with nature (Taylor,

2001) including having higher test scores in concentration, self-discipline (Wells, 2000),

and a sense of wonder (Louv, 1991). In addition, play in outdoor environments increases

cognitive development by improving reasoning and observational skills (Pyle, 2002), and

creativity (Crain, 2001). Social-emotional development is also affected positively by

outdoor play in studies which have shown that being in nature helps children feel a sense of

peace (Crain, 2001), allows children to deal with adversity more effectively (Wells, 2003),

develops more positive feelings about themselves and others (Moore, 1996), and develops

a sense of independence and autonomy (Barllett, 1996). The guide also includes benefits to

language development through outdoor play such as, a greater and more complex use of

language, inspired by first hand experiences. These real life experiences allow children to

build mental representations of “complex phenomena, process complex language, and then

can attempt to communicate their understanding of those experiences with others (French,

2004).

8

Methodology

The purpose of this project was to create a guide for parents called “Parent’s Guide

to a Healthy Start”. This guide aimed to be concise and easy to read for parents living in

the Sacramento area. The targeted demographic population includes parents living in

Sacramento County who attend the Children’s Center at California State University,

Sacramento and the parents of children enrolled in ten Spanish-speaking Family Child Care

Homes (FCCH). The resources listed are limited to the Sacramento area. However, parents

living in any city can implement the outdoor activities.

Literature on complimentary benefits of physical activities, outdoor education, and

healthy diets and the influences those variables have on children’s development was

reviewed. This review gathered information on the benefits of engaging in outdoor

activities and some of the negative consequences of lack of outdoor play and unhealthy

eating habits. After completing the literature review, the researcher looked into existing

resources for parents to determine which of these materials focus on outdoor activities. The

researcher found that there are multiple books and websites that give ideas for outdoor

activities, but these resources did not address all of the topics the researcher considered

necessary for parents to understand the importance of engaging in outdoor play activities,

including specific benefits for cognitive, social-emotional, and language development for

preschool age children. Such a guide should not only provide helpful activities but also

should offer child development background information and a list of resources that support

9

parental efforts to engage in more healthy habits. The researcher created a simple, yet very

informative guide that includes the negative effects of sedentary lifestyles on child

development, the benefits of outdoor activities to cognitive, social-emotional, and language

skills, the benefits of healthy eating habits, practical activities with the developmental

domains that they impact, and local free and paid resources that support families in their

quest to include more outdoor activities and healthy diets in their daily routines. After

conceptualizing the format and type of guide needed to help parents, the researcher

returned to the empirical and theoretical literature to determine which specific facts and

information could be included in the guide to maximize its effectiveness.

Simultaneously with the literature review, the researcher looked for local resources

that support families to engage in outdoor activities and healthy eating habits. The

researcher found information about community gardens and farmer’s markets in

Sacramento county and local activities such as Nimbus hatchery and the American River

bike trails. Each of the resources found were visited or discussed over the phone to confirm

they were still available. The current local resources found were included in the final guide

with necessary contact information to make it easy for parents to visit those sites without

having to do their own research.

10

Definition of Terms

For the purpose of clarity, the following terms are defined:

Obesity: Body Mass Index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same

age and sex as defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physical Activity: The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all

children 6-13 engage in three types of activity: aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bonestrengthening. However, for the purpose of this project physical activity is defined as all

outdoor and indoor activities that promote movement. That is, any activity in which the

child is not sitting down and is engaging in some type of movement.

The following definitions have been adopted from the California Preschool

Learning Foundations (PLF) and the Infant/Toddler Learning and Development

Foundations developed by the California Department of Education (CDE) and WestEd.

These are seen as the necessary competencies that preschoolers, infants and toddlers

should be developing in order to be more successful in school. There are other definitions

in the literature for each of the following developmental areas. However, the researcher

chose the definitions offered by the Preschool Learning Foundations and the

Infant/Toddler Learning Foundations (ITLF) published in 2008 by the CDE because all

publically funded Early Childhood programs in California are required to utilize these

resources. The Foundations offer specific definitions of the skills and knowledge children

between the ages of 48 months and 60 months (4-5 years of age) and birth to 48 months

11

should demonstrate. These skills and knowledge have been divided into domains that

have been directly correlated to kindergarten readiness. Most teachers in public schools

and some parents may be familiar with the Foundations’ domains because the CDE and

WestEd have been doing intensive trainings and are currently working on developing

more trainings to disseminate the PLF and ITLF to all early childhood teachers in

California. Due to the broad dissemination of the PLF and ITLF, choosing these

definitions to be used as the basis for the guide will make it easier for parents to align the

knowledge they get from this guide with the information teachers are offering to them.

Cognitive Development: When this domain is mentioned, it refers to the children’s

change in mental abilities such as thinking, reasoning and understanding. This domain

includes the children’s understanding of cause-and-effect, spatial relationships, problem

solving, imitation, memory, number sense, classification, attention maintenance, and

symbolic play.

Language Development: When this domain is mentioned it refers to the children’s ability

to listen, speak, read, learn new vocabulary and learn about print.

Social-Emotional Development: This domain includes children’s self-awareness, selfregulation, and social interactions with adults and peers.

It is the goal of the Guide that children will also build a strong relationship with nature

and learn how they connect to and affect their natural environment.

12

Limitations of the Project

Currently both parents work and many have to commute long distances, preschool

age children are being brought to child care centers that are servicing a high number of

children. Currently, some children attend childcare centers that offer little or no outdoor

play. In some instances, this lack is due to ignorance about the benefits of outdoor

activities but other times is due to a fear of financial liability if a child is injured while

playing outdoors. Some parents share the fear that their children could be more likely to

become injured outdoors than in a more restricted environment indoors (Prezza,

Alparone, Cristallo, & Luigi, 2005). Another limitation is the fear of crime outdoors,

which is very difficult to assuage for both parents and childcare workers caring for young

children. Because of these fears, sedentary life styles are likely to continue until safety

concerns are resolved (Farrall, Bannister, Ditton, & Gilchrist, 2000). Another limitation

of this project is that it was not piloted with parents or ECE professionals due to time

constraints. In further work by the researcher, Parent’s guide to a Healthy Start will be

distributed to parents enrolled in 10 local family child care homes (FCCH) and to the

Children’s Center at California State University, Sacramento. These FCCH’s and the

child care center have been approached by the researcher and are interested to review the

final product before dissemination to the families enrolled in the child care facilities. The

guide will support those facilities’ efforts to engage the children and their families in

more effective outdoor experiences.

13

Organization of the Project

This chapter has provided an overview of the project design to create a guide

titled “Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start”. Chapter two offers the literature review about

outdoor play benefits, negative effects on sedentary life style which include effects to

physical, emotional, and language development. This chapter also includes findings of

the effects of eating habits towards child development and some of the roles parents can

have to encourage healthy eating habits and active outdoor play. Then, chapter three

describes the layout of the project, how it was designed, and the steps the researcher took

to create this “Parents guide to a healthy start”. Finally, chapter four lays out the

conclusion s and limitations of the project and offers some suggestions for further work

in the area covered by the project.

The guide offers information about the benefits of outdoor play activities and

healthy eating habits for preschool age children’s healthy development. The information

found in the guide is supported by the literature review summarized in chapter two. The

guide is organized into five sections. Section one summarizes the benefits of engaging in

outdoor activities and some of the negative effects of sedentary life styles. Section two

gives parents an overview of the United State Department of Agriculture (USDA)

guidelines for healthy diets and includes community resources that support this goal in a

financially sound way. Section three includes information about how gardening can

14

support both healthy eating habits and outdoor play, and offers directions on how to

create a home garden and implement gardening activities. This section also lists

community gardens in the Sacramento County. Section four includes activities designed

for children ages three to five years that will help parents include some outdoor activities

in their daily lives. This section begins with vignettes that allow parents to better

understand how specific activities provide opportunities to support cognitive, socialemotional, and language skills. Each activity has a description of the developmental

domains that it promotes so parents can feel confident about what their children are

learning during play. Section five includes a list of paid and free outdoor play resources

in the greater Sacramento Area such as the American River bike trail and other walking

trails, Nimbus hatchery, public pools, and farms. The outdoor resources listed give

parents ideas of activities that are available to them as they seek to include outdoor play

in their routines. All sections of the Guide can be found in Appendix A.

15

Chapter 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Demographic areas

The United States has gone through multiple changes in the last century that have

affected the ways children engage in outdoor play. The Census Bureau data (2001)

showed that in 1850 ninety percent of the population in the United States lived in rural

areas. These living conditions were favorable for outdoor free play for both children and

adults because there were many accessible woodlands, riverbeds, and farmlands (Pyle,

2002). However, in 2001 only ten percent of United States population lived in rural areas

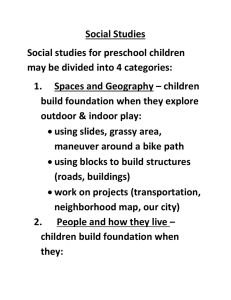

with most families living in suburban neighborhoods (See figure 1). The information for

this figure was found in the Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing

Unit, PHC-3 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) and the graphic was created by the researcher.

Figure 1.

16

Currently, many suburban neighborhoods are built to house high numbers of

people but do not consider the importance of “connectivity.” Connectivity is defined as a

convenient layout for people to be able to go from one side of a neighborhood to the

other without having to take a long or heavy traffic route (Committee on Environmental

Health, 2009). Connectivity allows children and families to engage in outdoor activities

such as biking to school, walking to the market, getting to parks easily, and finding open

areas to play without the dangers of vehicle traffic. Therefore, neighborhoods that lack

connectivity have a negative correlation with the amount and kinds of physical activity

and outdoor play for residents.

Furthermore, there has been an increased parental fear for outdoor child safety

due to excessive information about crime and accidents (Hillman, 2000). Clemments

(2004) studied mothers of children 3 to 12 years old and found that 82% of them did not

feel comfortable with their children playing outdoors alone. Their safety concerns include

potential injuries and sexual predators that could endanger children with limited

supervision. Because of this growing fear there has been an increase in the number of

children who participate in organized sports instead of free outdoor play (Saelens, Frank,

Auffrey, Whitaker, Burdette, & Colabianchi, 2006). Studies have found that organized

sports support children’s physical activity and that this activity could carry on to adult

years (Crawford, 2005). However, the researcher could find no peer-reviewed studies that

17

address the benefits of organized sports for children under the age of seven and how

those activities impact different developmental areas for these younger children.

On the other hand, many studies find support for free outdoor play for children

from birth. Findings include significant positive influences on cognitive development

including: increasing initiative, imaginative play, creativity, understanding of the use of

tools to accomplish a goal, and basic academic concepts such as investigation and

production (Singer & Singer, 2000). Contrary to the connectivity theory, some studies

found that a more influential factor for children choosing to be physically active is the

home environment and not the neighborhood layout (Roemmich, Epstein, Raja, & Yin,

2007, Saelens, Sallis, Nader, Broyles, Berry, & Taras, 2002). For example, the number of

TVs and videogames used in the home, meal times in front of the TV, and parental

sedentary life choices had a negative correlation with children spending less time

outdoors or engaging in physical activities (CDC, Health Consequences, para. 3). Thus,

child development is enhanced by outdoor play, and the amount of outdoor play children

experience may be influenced by community design as well as parents’ life styles.

School changes

In addition to social and environmental changes there have been changes in the

availability of outdoor physical activities during school hours. The No Child Left Behind

Act (NCLB) is a law put into effect by the US Department of Education in 2001, which

emphasized school focus on reading and math subjects with the goal to close the

18

educational gap for disadvantaged students. Hendrie (2005) explained this emphasis

created a lack of balance between academics and children’s developmentally appropriate

needs to have hands-on, active undertakings to develop healthy cognitive, socioemotional, and language skills, all of which are fundamental for school success. The US

Department of Education and local school districts’ aims were to better prepare students

for higher education, and to be able to compete with future generations in the global

market. Nevertheless, NCLB created a culture of preparing for tests and assessments

(Persellin, 2007) and limited the amount of free outdoor play, which ironically has been

found to increase skills needed for math and reading such as willingness to stay on task

and problem solving (Leiberman & Hoody, 1998).

In the past, students had more opportunities for hands-on experiences with

activities that were preparing them to deal with the lifestyles and work in their

communities. Children and families spent more time being outdoors building things,

caring for their crops and animals, exploring, experiencing and learning from nature

(Dollman et al, 2012). Currently, school districts are faced with the high stakes given to

standardized testing, including whether or not schools will be able to maintain local

administration and Federal funding (Osburn, Stegman, Suitt, & Ritter, 2004). A

comprehensive academic review on the impact of standardized testing noted that

standardized testing has been present since 1920 when the Stanford Achievement Test

(SAT) started being used by schools to test their student’s academic achievement.

However, it was not until 1970 that the SAT gained as much interest as it has today. In

19

2001 with NCLB additional assessments were required. Originally, it was thought that

such tests would help find promote more effective teaching practices (Mulvenon,

Stegman, & Ritter, 2005). Hursh (2005) states NCLB and standardized testing has forced

teachers to teach and students to learn for the test, due to the fear that if students do not

perform well in standardized tests funding could be lost for low performing schools. In

many instances, the push for performance has sacrificed the need most students have to

spend more time experimenting with the concepts and educational materials hands-on

instead of rushing through many concepts without the opportunity to gain in-depth

understanding (Hursh, 2005). No surprisingly, the push for performance limited time for

outdoor activities. Such conditions were mitigated in prior education systems, which

allowed parents, teachers, and communities the power to make decisions over the needs

of the local student population and the appropriate subjects, including sports, to be taught

(Hursh, 2005).

The current system governed by state and federal regulations has a clear set of

academic standards and expectations for the performance level children need to achieve,

forcing children to be able to demonstrate proficiency in various curricular topics by

scoring above an average score designated by the federal government. That change

eliminated the opportunities schools had in the past to create curricula that addressed

community specific subjects (Hurst & Martina, 2003). Hursh (2005) criticized this

practice by noting that it forces the schools to teach multiple subjects covered by the test,

but does not offer extra time or funding to include outdoor, hands-on experiences that

20

will allow students to gain the physiological and academic foundations needed to be

successful in their education and in their lives.

Although we know standardized testing is considered important in our current

academic environment, it is not clear how it affects children, parents and teachers in the

long-term perhaps reducing children’s opportunities to engage in outdoor play, which

ironically enhances development and skills that would support higher academic

performance. “A recent survey sponsored by the Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development found that many parents are confused about standardized

testing, do not feel informed about assessment procedures, and do not believe they are

equipped to assist their child in preparing for testing” (Gleason, 2000 as cited by Osburn,

Stegman, Suitt, & Ritter, 2004 p. 77). These same parental concerns included that if

children did not achieve good scores on those tests they will not be successful later on in

life. Some of the parents reported that children need to spend time studying instead of

wasting time playing, a misconception shared by many parents who separate play from

learning and do not see how play facilitates learning via hands-on experimentation

(Rothlein & Brett, 1987).

Teachers reported a high level of anxiety due to the standardized testing. Teachers

feared that the results would be unfairly used against them to decide salaries or

continuation of employment (Mulvenon et al., 2005), which increased the emphasis of

“teaching to the test.” Children whose parents put very high or very low importance on

standardized test were found to score lowest on the tests possibly due to lack of

21

understanding of the tests by parents (Osburn et al., 2004) Based on the literature review

it is possible that those children could have been spending too much time studying and

were missing out on other activities that could have helped them build the developmental

competence needed to excel. In contrast, children whose parents considered standardized

testing important, but did not place a significant value on them, scored higher than the

former group. These results are affected in part by parental attitudes. Parents who place a

high value on test scores tend to place a higher value on academics and less on outdoor,

hands-on activities. The literature reviewed supports the assertion that outdoor activities

“…[foster] flexible and divergent thinking and provide(sic) opportunities to meet and

solve real problems” (Staempfli, 2009, p. 272), skills needed to succeed in the real world,

including doing well on standardized tests.

Benefits of outdoor play

Notwithstanding that academics and safety play an important role in a child’s

development, limiting our children’s interactions with the outdoors has created a

disconnect with how academic topics learned in school relate to their reality in the

physical world. Children are loosing connections with the natural world, which not only

negatively impacts their cognitive, socio-emotional, and language development but, also

hinders the development of a whole, healthy person. Many studies have found that

children who have constant opportunities to interact with nature learn to love and protect

natural settings and to have positive environmental ethics (Pyle, 2003, & Sobel, 1996 &

22

2004). Wilson (1993) explained that humans have the evolutionary need to interact with

nature. When children are allowed to spend time outdoors playing in nature, they have

opportunities to observe, explore, and discover. Such children have been found to engage

in the active use of their imagination and develop stronger language skills (Fisher, 1992,

Carson, 1998). In addition, Fjortoft (2001) found that children who spend time in natural

landscapes develop significantly higher levels of motor skills such as balance, flexibility

and climbing abilities than children who played indoors and in structured playgrounds.

Children who play outdoors, in natural landscapes have also been found to have higher

levels of creativity and a deeper understanding of how things function in real life (Rivkin,

1995). These children tend to develop long-term positive attitudes towards science such

that they more easily learn about measurements, problem solving, and the climate

(Harland & Rivkin, , 2000).

The disconnect from natural outdoor experiences has exacerbated by an increase

in screen forms of entertainment also known as new media, which includes TVs,

computers, and videogames readily available to children of all ages in rural, suburban and

urban areas. In 1950 only 9% of households in the United States owned a TV set and in

1980 at least 55% of them did (Andreasen, 1994). This significant change, along with the

availability of many forms of new media has triggered an increase in research about the

impact these media devices are having on children’s development.

There is an on-going debate about the costs and benefits of new media on child

development. Some research finds that videogames and computers may help children’s

23

brains with memory, face recognition, and attention (Anderson, Fite, Petrovich, &

Hirsch, 2006) and allow children to learn skills needed to succeed in the modern job

market. Playing videogames has been correlated to increased problem solving skills.

However, video games take time away from reading and social interactions which have

been shown to increase externalizing behaviors for boys and to decrease vocabulary and

reading skills for girls (Hofferth, 2010).

It is important to note that TV, videogames and computers have been linked to

sedentary lifestyles that can lead to obesity over time, especially for children who have

poor dietary habits (Proctor, Moore, Gao, Cupples, Bradlee, Hood, & Ellison, 2003).

Children who spend long hours being sedentary are not likely to engage in physically

active play to make up for the time spend being inactive (Dale, Corbin, & Dale, 2000).

Sedentary lifestyles have been studied both during childcare hours and at home. Findings

include over one-third of children under three years old live in homes that have a

television on most of the time or always, even if no one is watching (Rideout & Hamel,

2006) and outdoor, creative play is limited. Children who spend significant time with

background TV, tend to have less interaction with adults and do not engage in as much

solitary play as do children in households where the TV remains off (Kirkorian, Pempek,

Murphy, Schmidt, and Anderson, 2009).

In addition, due to the societal changes mentioned earlier, recent studies find that

children spend the majority of their time at home involved in sedentary activities such as

watching TV, playing video games or in front of the computer screen (McIver, Brown,

24

Pfeiffer, Dowda, & Pate, 2009). Surveys report that 28% of youth in US watch more than

4 hours of TV per day and some families even have most of their meals in front of the TV

(Marshall, Gorely, & Biddle, 2009). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends

that children under the age of two do not watch television at all, and that children over

two years of age watch no more than two hours a day (American Academy of Pediatrics,

2001a). Reducing the number of meals eaten in front of the TV is correlated to a decrease

in obesity (Robinson, 1999) and the increase of social interactions with adults and peers

than allow children to develop vocabulary and a sense of belonging (McIver et al, 2009).

In addition, the 50.6 percent of children under 5 years old spend at least 35 hours

in childcare settings (Capizzano, & Regan, 2005). This finding reinforces the need for

parents to pay close attention to the quality of the care their children are receiving. While

parents might believe that childcare offers plenty of outdoor play, Christakis, Garrison,

and Zimmerman (2006) found that 35% of preschool age children who attend child care

centers spend a significant amount of time watching TV and 85% of children attending

family child care home do as well.

Play deprivation

Recently, negative effects of inactivity and unhealthy diets have been at the

forefront of research studies due to the significant increase of negative health and

developmental effects being seen in young children. Amongst those negative effects are

cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and type II diabetes (CDC, Health Consequences, para.

25

1). Children across all demographics have been affected but African American, Hispanic

and low-income children have higher prevalence of obesity mainly due to sedentary lives

and diet, which are caused in part by unsafe neighborhoods and consumption of low-cost,

low-quality food and drinks (Hass et al., 2003). Inactive children have also been found to

be at higher risk for physical, emotional and cognitive diseases including “…bone and

joint problems, sleep apnea, endocrine abnormalities, and social and psychological

problems such as stigmatization and poor self-esteem in comparison to” physically active

peers (Breslin, Morton, & Rudisill, 2008 p. 429). Furthermore, obese children have

higher rates of school absences due to health factors, lower self-esteem, and higher

depression rates (Datar, Sturn & Magnabosco, 2004). In response to these alarming side

effects, the US Department of Health & Human Services in its Healthy People Guidelines

2020 (Key Guidelines, para. 2) recommended that all children engage in at least one hour

each day of moderate to strenuous physical activity to reduce obesity and depression and

to increase cognitive abilities. The Key Guidelines also recommend that all children be

encouraged to play outside.

Another statistic to be considered is that over 60% of preschool age children in

the United States are currently attending center based child care (Federal Interagency

Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2008) and although the information about physical

activity during child care hours is limited, the findings so far are less activity than

expected. As mentioned earlier, schools have decreased the amount of outdoor play

offered to children; however, parents believe that their children are being more physically

26

active during preschool and grade school than they actually are. One study found that

preschool children engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity only 3% of the day in

child care, while 80% of their time they engage in sedentary activities (Pate, McIver,

Dowda, Brown, & Addy’s, 2008) Surprisingly, this includes 60% of their outdoor time

because adults do not allow them to choose activities that could pose injuries (Sallis,

Patterson, McKenzie, & Nader, 1988). The sedentary activities include mainly adult

initiated activities such as TV viewing, computers, nap time, large group activities, snack

time, and playing with manipulative materials (Brown, et al., 2009). Although boys are

typically found to be more active than girls, there are many gender-neutral activities that

could encourage both genders to be active but this has not been seen in the studies. An

important finding is that children are more physically active when under the care of

adults who have been trained on the benefits of outdoor play (Bower, et al., 2008).

Healthy Diets

As mentioned earlier, research has found that in order for children to develop

healthy bodies and minds, active play and a healthy diet need to be included in all

children’s routines. Trost, Sirard, Dowda, Pfeiffer, and Pate, (2003) noted that children

who become obese in early childhood are less likely to engage in active play and social

activities and have a higher incidence of continuing to be obese throughout their entire

lives. Therefore, the types of diets offered to children have a significant effect on

children’s near-term and long-term choices and health outcomes, as well as a direct effect

27

on their physiological health. Children need to have access to water, fruits and vegetables

rather than soft drinks that have high amounts of high fructose corn syrup and sugar in

order to keep a healthy weight (Silva-Sanigorski, et al, 2010) and a balanced, nutritious

diet.

Unfortunately, the increased accessibility and advertisement of fast food chains

around many neighborhoods, and the availability of processed meals makes it very

common for parents to buy and allow children to eat these unhealthy meals. In some

cases it is cheaper to buy high fructose sugar drinks instead of making fresh squeezed

juices and many parents are under the impression that some of the packaged meals

contain healthier choices than they actually do because of the misleading word choices on

product labels. It is vital for children to be offered and encouraged to eat healthy diets

from birth in order to develop healthy eating habits that sustain good health and prevent

chronic illnesses and/or health risks.

A report by Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, and Flegal (2010) noted that 9.5% of

the infants in the US were “at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbentlength growth charts” and 40% of children aged 2 to 19 years were “at or above the 97th

percentile of the BMI-for-age growth charts” (p 243). The CDC showed that “obesity

prevalence increased 0.43 percentage points annually during 1998—2003” for preschool

age children (CDC, Childhood Overweight and Obesity, para. 2) and

recommended that children be offered food choices that are low in fat, calories and added

sugar. A longitudinal study done in the UK found a positive correlation between low

28

quality “junk” food and sugar intake with hyperactivity at age 4 ½ and higher rates of

obesity. The authors speculated that the cause of these results was that junk food is

packed with additives, sugar and fats (Wiles, Northstone, Emmett, & Lewis, 2009). Food

coloring and preservatives have been associated with higher rates of hyperactivity and

inattentiveness (Leickly, F., 2005); high intake of cholesterol appears to be associated

with low scores in short term memory tasks, whereas intake of fish, bread and cereal is

correlated with higher IQ (Theodore et al, 2009). Thus, some children who have been

diagnosed with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder may experience improved

behavior and attentiveness once artificial coloring and preservatives are removed from

their daily diets (Greene, 2011).

Furthermore, parental role modeling of healthy eating and active life styles has

been found to be one of the most significant factors influencing children’s healthy

choices (Campbell et al., 2008). This means children who live in families in which adults

eat fruits and vegetables, eat more vegetables and fruits themselves and avoid unhealthy

choices as they get older.

Parents’ role

Preschool age children spend much of their waking time interacting with objects

in their environment and trying to make sense of those interactions (Piaget, 1962). Play is

free, intuitive interactions that occur without much planning by the child but adults have

the power to help make it more meaningful by offering environments that encourage

29

active engagement (Ginsburg, 2006). Unfortunately, parents are at times misinformed

about the educational needs of their children because of the confusing information

offered about standardized testing and school entry requirements mentioned earlier. Toy

manufacturers also advertise materials that purport to improve child development, that

are at best unnecessary and at worst encourage children to be overly sedentary, for

example "Baby Einstein" and "Brainy Baby" series (Zimmerman, F. J., & Christakis, D.

A. (2007).

Parents are expected to equip their children with the skills and experience

necessary for autonomous living, including exposure to real life experiences,

understanding of the real world, problem solving, and some exposure to risk. According

to Richard Louv (2005), parents need to give children opportunities to explore, and

develop complex play. These opportunities include providing environments that can at

times challenge children physically and add some elements of risk. Opportunities for

risks combined with less fearfulness from the adults supervising the children are needed.

When safety is what drives the decision-making, a child often ends up lacking real life

experiences (Louv, 2005).

There are very few things in life that involve no risk, therefore, in order to live

safely children need to be able to interact with real objects and have encounters with real

dangers so they can learn how to protect themselves and take reasonable precautions in

the future. Such risks not only create children who have better physical balance and other

physical skills, but also children who are more confident and competent to watch out for

30

themselves. However, at this time many children are only being exposed to risk- free

environments (New, Mardell and Robinson, 2005).

According to Slovic, (2000) there is a psychometric paradigm, which describes

the perception of danger thus “risk is a highly subjective process… possible hazards are

identified and prioritized by factors [which are] influenced by a wide variety of social,

cultural, and psychological factors”. Unfortunately, children’s exposure to outdoor play is

so limited, that it is a concern for how development might be restricted or altered in ways

that are not adaptive over the life span. Parents need to learn to create a balance between

quality learning experiences and supervision with the goal of allowing children to be

active learners in their environment. Children have been found to be more active when

adults offer quality outdoor environments that include open spaces, balls, riding toys,

wheels and the opportunity to learn games (Brown et al., 2009). In addition, music both

indoors and outdoors can promote vigorous physical activity when adults direct music

activities such as dancing.

Moreover, parents should allow children the opportunity to initiate and lead

outdoor activities as those have been found to be more physically demanding than most

adult initiated activities (Sallis et al, 1988) Conversely, children develop a higher sense of

autonomy and problem solving when allowed to direct outdoor activities. However, adult

lead activities can result in quality physical activity when they organize, model,

encourage and acknowledge children’s physical activity and have it as the goal of the

activity (Brown et al, 2009).

31

Theoretical Framework

It is important to recognize how preschool age children build knowledge about the

environment around them in order to be able to offer age appropriate, quality experiences

that best fit a child’s needs. There are many theories out there about how children build

cognitive, socio-emotional, and language development (Blank & Berg, 2006).

Importantly, all of the developmental domains are interrelated and strongly supported by

outdoor play experiences, as those experiences allow for individualization and hands- on

interactions with the world in a less restrictive environment.

Cognitive Development theory

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is an active stage approach that focuses

on how a child’s interactions with objects and people in the environment spur the child to

mature from one stage to another. These interactions become more systematic behaviors

and thought processes that change over time with new and more complex experiences.

The stages Piaget identified are named sensorial (birth-2 years), preoperational (2-7

years), concrete operational (7-11 years), and formal operational (11-15 years). This

project focuses on the preoperational stage that includes children from 2 years old to 7

years old (Piaget, 1976). Piaget believed that the way children understood the world was

by basic mental structures called schemes. Schemes are organized mental patterns that

adapt and change as children are engage in to new experiences. Children in the

32

preoperational stage learn best through active engagement rather than passive instruction.

In addition, children at this stage are egocentric meaning they are unable to see things

from another’s perspective. Piaget’s theories and research has lead others to conclude that

active participation is mandatory for children to learn. Outdoor play allows children to

engage with the world actively. They can interact with the world around them at their

own pace. These open interactions facilitate each child’s gathering information from the

outside world, adapting themselves to new information and experiences, enabling them to

navigate the world more successfully (Piaget, 1976).

Bruner (1977) argued that for children to be able to learn, remember, and be able

to transfer knowledge from one area to other areas of life, they need to first be able to

understand the foundation developmental competencies of the subject at hand. Bruner

also argued that knowledge is linked from one subject to another and that no one

experience stands in isolation. For example, as children learn about how to tie their shoes

they are more able to connect this knowledge to how to tie a knot to build a fort or to put

some ribbon on a gift box and so on.

In the past, children learned the skills they needed to succeed in their societies by

helping their families with chores such as caring for the farm animals, building furniture

or cooking for family members. Currently with the large industrialization of our society,

children are learning concepts at school taught in settings “remote from where they will

ultimately be used” (Gardner, 2000, p. 29). Because of it, many fundamentals

developmental competencies have not been learned which has made future learning less

33

enjoyable and far more difficult than if the fundamental concepts were learned since early

age.

Language Development Theory

Many have debated how language development occurs. Nativist theorist such as

Chomsky believe that children are born with the innate mechanism for developing any

language and that it is how our brain is wired what allows children to understand and

reproduce language as they mature. Other theorists, such as Vygotsky, believed that

language develops from social interactions for children to communicate. Once children

recognize that each object has a name language begins to merge with thinking and

understanding. Vygotsky (1962) also recognizes that language plays a role for cognitive

development as adults use it to transmit information to children and then children use it

as a tool to learn more about their environment. This later he described as a crucial

moment in which the child becomes very curious about words which leads to a quick

increase in vocabulary.

Vygotsky, as well as Bruner, believed that children learn in the context of social

interaction by interacting with the environment around them. Vygotsky explained that

children operate at one level when they work on something on their own but can perform

at a higher level when scaffolded by an adult or more experience peer. The latter being

the potential development level. Vygotsky referred to the gap between those two levels as

the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). Once this new level of functioning

34

is internalized, the child can independently use the knowledge gather from the scaffolded

interaction and move on to a higher level of development. Then this child can engage in

other interactions with the environment and a more experience peer to be scaffolded to an

even higher level of development. Language is learned through social interaction and it is

especially affected by children’s exploration of their world and direct interaction with

others. Although language affects children’s conceptual development, Vygotsky believed

that speech and thought are two separate functions. Outdoor play allows for children to

engage in a significant amount of symbolic play in an unstructured environment.

Symbolic play offers opportunities for children to use objects in any imaginable way and

transform it into anything. Vygotsky saw these play opportunities as revolutionary and

needed for children to think in creative ways that lead to higher cognitive functioning.

This work by Vygotsky and Bruner directly affects the researchers work on the

importance of children interactions with outdoor play for both language and cognitive

development.

Socio-emotional Development Theory

Preschool age children need to develop socio-emotional competencies to be able

to interact effectively with the world around them and others. Epstein (2007) discusses

that a child’s lack of emotional regulation affects relationships with others because it

does not allow for them to understand the appropriate range for reacting to situations.

Children need to learn from their social interaction about the social norms and customs,

35

including way to appropriately interact with others and to learn how to deal with

disagreements and other personality traits. It has been found that children think that

adults expect them to be quiet indoors while outdoors play allows them to feel free and

engage in more cooperative play with other children and adults (Bilton, 1998). This

cooperative play gives children opportunities to practice and interact with social norms

and a range of situations that give then bases for socio-emotional development. This

study also found that when both boys and girls play outdoors they are more physically

active, and are more keen to learn through exploration and acting out. Also, these

children engage in more imaginative games with others, and are more willing to follow

each other’s leads.

Attention Restoration Theory

Attention Restoration theory (ART) “hypothesizes that natural environments

enhance psychological health and well-being by allowing individuals to reduce mental

fatigue and replenish the mental abilities necessary for self-regulation, which is a child’s

ability to gain control of bodily functions, manage powerful emotions, and maintain focus

and attention. ART has also been found to increase cognitive inhibition known as the

ability to control internal and external distracting stimuli that can help enhance attention

levels (Duvall, 2011 &, Shonkoff, & Phillips, (2000). Addressing the finding that

physical activity and outdoors can affect attention levels, Holmes, Pellegrini, and

Schmidt (2006) examined the effect recess has on a preschooler’s ability to focus by

observing children’s attention level prior to a recess period and immediately following a

36

recess period. Holmes et al. found that children were more able to focus during the

reading of a story when they returned from a 20-minute recess period of outdoor play

than during days when children could not play outdoors due to time of weather

constrains. It is likely that the limited opportunities of outdoor activities currently in

school has an effect for children attention during school hours.

In addition, preschoolers who have had limited exposure to outdoor activities are

likely to have less number of playmates and exhibit poorer levels of social abilities when

entering school (Zaradic & Pergams, 2007). This could be because children who spend

most of their days indoors do not have as many opportunities to play with other children

and their families tend to live in more isolation than families who spend more time doing

activities outdoors. This could be, in part, affected also by the connectivity theory, which

allows children and families to engage in outdoor activities such as biking to school,

walking to the market, getting to parks easily, and finding open areas to play without the

dangers of vehicle traffic.

Conclusion

It is expected that parents look for ways to ensure that children get the best

opportunities possible available to them by trying to offer activities that support cognitive

development. Unfortunately, as this literature review has outlined, lately much of the

efforts have focused attention on indoor academic development and limited outdoor

37

experiences including sports, arts, and various hands-on activities due to financial

limitations, curricular demands forced onto the school systems by state and federal

regulations, and parents’ misconception of what is needed for children to develop. These

regulations have forced children to learn in a fast-paced curriculum and lack connection

with natural environments found outdoors. Some of the curriculums developed by

schools after NCLB was implement are at times too difficult to understand because the

fundamental concepts need it were taught too quickly and without opportunities to

experience the concepts hands-on. The literature in this chapter has shown evidence that

there is a need for a conscientious increase of outdoor play activity for children, as well

as the need for learning about healthy eating habits that will help children be healthy.

38

Chapter 3

METHODS

Our society has seen rapid changes in our way of life from rural to suburban and

urban living in the last century, which have affected the amount of free outdoor play

children experience. In addition, there are two additional changes in the last decade that

have further reduced outdoor play. California’s schools have faced economic challenges

due to reduced resources for education and structural challenges due to the NCLB

regulations placing too much emphasis on standardized test scores. The academic

regulations have pressured teachers to “teach to the test.” Parents are often not informed

about this over-emphasis on academics instead of a healthy balance between academics and

outdoor play.

Unfortunately, in the last decade, many schools including preschools and family

child care homes, have responded to NCLB and the concomitant testing by making

significant changes. Their curriculum has become more academic with much less time

spent in extracurricular activities including outdoor play, art, and music. To address this

unhealthy imbalance in curriculum the current project, “Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start”

is a first step to address this important issue.

The main focus of this thesis project is the development of a concise guide for

parents that will help them understand how outdoor play can be beneficial for their

39

preschool age children in developing higher cognitive, social-emotional, and language

skills. The guide covers (a) benefits of outdoor play (b) negative effects of a sedentary life

style, (c) benefits of healthy eating habits, (d) examples of outdoor play activities, (e) local

Sacramento county resources that help foster healthy eating habits, and (f) local

Sacramento resources that facilitate outdoor activities. There are written resources in the

marketplace that cover some of the topics in the current guide. However, a review of the

literature and other publications drew no results for a guide that covered the variety of

topics local parents need to have at their finger tips in order to understand the value of

outdoor play and be empowered to implement more outdoor play with their children.

Design of the Project

The first step in the development of a concise guide for parents on the benefits of

outdoor play for young children was a review of the literature. The researcher noted that

there is a direct link between both outdoor play and healthy eating habits with positive

developmental outcomes for children. Therefore, the guide includes a section on healthy

eating. The guide entitled “Parents’ Guide to a Healthy Start” was created to include the

information parents are currently lacking in order to encourage more outdoor play and

healthier eating habits in their children’s daily lives. First, the researcher examined the

literature about the benefits of outdoor play via Google Scholar, ERIC, PsycINFO, and

EBSCO host database, by using the search terms: outdoor play, nature, cognitive

40

development, language, outdoor education, physical activity, and play. This review

identified studies that examined the benefits of outdoor activities and the negative effects of

sedentary lifestyles. The literature review revealed a long history of study of benefits of

outdoor play on motor development, but less work has been done on other developmental

domains (Fjørtoft, 2001, Obeng, 2010, & McIver et al, 2009). Because of this, the

researcher decided to focus the literature review on the impact of outdoor play on socioemotional, cognitive and language development. Then, a more specific search was done

including outdoor play with these three selected developmental domains. This search was

effective in finding information about how outdoor play and healthy eating habits can

benefit these developmental domains. This search was used to organize and communicate

information in the guide to parents in an easy to implement style. The intent is to

encourage parents to learn ways to encourage more outdoor play for children in the

Sacramento area.

Once the literature review was completed, the researcher searched for websites and

books that offer ideas about age appropriate outdoor play activities. Then, the researcher

selected a few activities that could easily be adapted to various environments keeping

Sacramento County in mind. Then, those activities were modified when necessary to meet

the developmental level of children ages 2 to 5 years old, and to be useful in the

Sacramento area. In addition, the researcher noticed a lack of information about local

resources that are readily available to everyone, but not known by many. This lack of

knowledge was discovered through conversations with parents and child development

41

professionals in the Sacramento area. Thus, a list and brief description of Sacramento

county resources that support healthy eating habits was developed and included in the

guide. Examples of those resources are farmer’s markets, community gardens, and nature

centers in the area. These resources were found through online searches and the

researcher’s personal visits to many of them.

Online and book searches

Outdoor activities appropriate for preschool age children were selected after the

researcher read multiple books that have already been published about outdoor activities.

Not all of the books read by the researcher were used to create the activities included in the

“Parent’s guide to a healthy start” but a list of some of them was included in the guide for

parents to read if interested in more ideas for outdoor activities. None of the activities in the

guide are the same as the ones listed in any of the books but these resources were an

inspiration for the researcher.

Also, many websites were researched and used to find local resources that promote

outdoor play and healthy eating habits in the Sacramento county area. Those websites are

also listed in the guide for parents to find other resources and stay informed when new

resources become available.

This guide was created specifically for parents living in the Sacramento area and

keeping in mind that it will be disseminated by 10 family child care providers and the

Children’s Center at California State University, Sacramento to parents after is completed.

42

of children 3 to 5 years old. Keeping the population of parents in mind the guide was

design to include aspects found in the literature to be necessary for parents to know. The

guide begins with information about some societal changes that have affected the amount

of outdoor play children engage in. Then, it explains some of the benefits outdoor activities

have on cognitive, socio-emotional, and language development, including some

controversial ideas such as TV and computer being beneficial to children’s development

when there is a balance with outdoor play. After that, parents can find a section about the

importance of healthy eating habits and how those habits effect child development. That

section also refers to how gardening promotes healthy development of cognitive, socioemotional , and language areas, as well as healthy eating habits. Butterfly gardens are also

included in that section as they provide opportunities for interactions with nature and

outdoor experiences. Furthermore, the guide has a section that includes vignettes that

recount scenarios of children engaging in outdoor play. This vignettes further exemplify to

parents how outdoor play can benefit children’s cognitive, socio-emotional, and language

development. This section also includes 3 activities with their description for each of the

three developmental domains this project focuses on. After, parents can find a list of free

and paid outdoor activity resources for Sacramento county. Finally there is a list of books

and website that the researcher found helpful when looking for resources around

Sacramento area.

43

Procedures

In the first phase of the creation of this guide, the researcher reviewed the existing

literature by using Google Scholar, ERIC, PsycINFO, and EBSCO search engine. The

researcher noticed a reoccurring theme amongst search data topics, the negative effects of

sedentary life style and the benefits of healthy life styles, including outdoor play and

healthy diets. Throughout the research of the literature, the researcher found explicit