RECOVERING POTENTIAL A Thesis

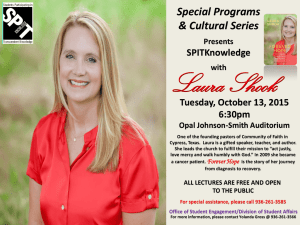

advertisement

RECOVERING POTENTIAL A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Art California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Art Studio by Laura Lani DeAngelis SPRING 2012 RECOVERING POTENTIAL A Thesis by Laura Lani DeAngelis Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Rachel Clarke, M.F.A. __________________________________, Second Reader Andrew Connelly, M.F.A ____________________________ Date ii Student: Laura Lani DeAngelis I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Andrew Connelly, M.F.A. Date Department of Art iii Abstract of RECOVERING POTENTIAL by Laura Lani DeAngelis Statement of Problem Art has been the catalyst to an existential investigation into how I exist in the world while seeking truth and meaning. My main concern regarding higher education was how the work would change, would I become a better artist and would my intentions shift significantly? Did the future hold some kind of resolve, offering myself and the work greater meaning? Sources of Data Two years of practicing studio art and being in the academic art world; unveiled psychic unrest; tests of mental strength and capacity; existing in a world of utter confusion and freedom. Conclusions Reached I’ve returned to where I started, yet with a conversion of consciousness. I don’t know what a “better” artist is, however, my work holds greater meaning. It seems that the strife somehow elicits fulfillment, while the successes and failures bring forth a dialogue that assist further development and add value to both the work and my person; offering potential for meaning. Higher education is humanizing, changing the work through a steady process of reduction, getting it closer to the essence of my intent. But concepts surrounding irresolution create the work, suggesting resolve to be unattainable. _______________________, Committee Chair Rachel Clarke, M.F.A. _______________________ Date iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures…………………………………………………………………...........vii Chapter INTRODUCTION.....………………………………………………...…………….….1 IGNORAMUS…….. ....…………………………………………………………….…2 PSYCHIC UNREST ..............................................................................................……5 SHAME..........................................................................................................................7 BEING………………………………………………………………………………..10 CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………….13 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..23 vi LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph……….…...…..………….14 2. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph……...................................14 3. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph …………………………..15 4. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph ……………………..……15 5. The Cold War, 1999, Sandy Skoglund, color photograph, www.sandyskoglund.com (accessed on 5/1/12)..................................................16 6. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph..………………………….16 7. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph …………………….…….17 8. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph …….………………….…17 9. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph .………………………….18 10. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph ………………..................18 11. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph .…………….....................19 12. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph ……….……………...…..19 13. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph ….………….....................20 14. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph …......................................20 15. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph...........................................21 16. One, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still..……………………………….……..21 17. Two, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still..………………………………….…..22 18. Three, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still..……………………….....................22 vii 1 INTRODUCTION The empty frame elicits a moment of potential. As scattered thoughts struggle to gather themselves in an early attempt at composure, ambient sounds merge into a sea of abstraction. Perception between body and surrounding elements diminish to intangibility as if trapped in a void of uncertainty. A composition is somehow made, though only as one susceptible to disruption. This inward reflection is subjective and selfish. Embodiment is blinding, fighting the undercurrent of paradox while striving to justify truth. Mere existence is abandoned and sought again, masked by the façade of artificial realities. Reduced to a breath, balance contends with desire and discipline. Finally immersed in a state of presence, the body relinquishes control to nature’s transience. The strife itself sheds a residue of self-worth, though one must give something of oneself to attain it. Now bearing the weight of experience, potential is once again restored. This is where I begin. This is where I will end. 2 IGNORAMUS In regards to the photographer, a world is born from a set of hands and eyes. My investigations began in a small empty studio with a slanted ceiling, limiting full use of the space. A decent amount of wall and floor lent themselves to possibility, begging for a seed to be planted. In response, the conundrum with intent started: How do I speak to something I know nothing about? All I knew of this existence was that of my own body, of self, which I used as a vehicle to communicate something of subjective experience. I was interested in how the figure interacted in space. After absorbing the space, it was ego that took over, merely aiming to make a strong impression on the audience. It seemed my interest was in eliciting an immediate response from the viewer, in their reaction to viewing something strange, dream-like or absurd. With expectations high, I decided to make self-portraits that reflected the complexities of existence through colorful and startling tableaus (Figures 1-4). In retrospect, I wonder if I was simply trying to prove something to myself and confirm my person as artist. Surges of ambition lead me to a complete transformation of the studio, photographing my body configured differently in space while analyzing my reaction to the shifting props and environment. Painting everything in sight, I began to think more about color choices as glimpses of Sandy Skoglund photographs came to mind. Her fantastical interiors communicated ideas of chaotic realities, something I too was very interested in. With incredible attention to detail and humorous use of artificial materials (Figure 5), Skoglund’s work urged me to think more about the possibilities of the 3 controlled studio environment. Perhaps it was the knowledge of her work that influenced me to paint everything, and I was simply channeling an artist whose work I adored. Considering the potential for weak reproductions, I had to avoid the risk of being too derivative of another artist. Questions regarding intent piled on as layers of paint accumulated on the floor, walls and various props. The work had made progress as the dialogue trailed behind. The surface quality of the photographs was unintentionally being reduced as the monochromatic space threatened to flatten out, while the literal read of painted surface created a barrier in need of destruction. As the complexity of understanding my own work increased, I struggled towards resolve. I began deconstructing process and formal choices of image composition while making short rants in my sketchbook attributing dreams as the inspiration with intervention taking over image production; the result a visual response to my psyche. Through seemingly weak attempts to creating a dialogue, I realized I was trying to defend something I knew nothing about. It appeared I was interested in maintaining the notion that the work speaks for itself. I found it valuable to research the writings and interviews of other artists, as there was a common vocabulary, a conversation in progress. For years, I had maintained a salty impression of how artists spoke about their work. It seemed strong work was blatantly obvious and never required pretentious analysis of what it really meant. I deemed that artists made up bullshit about the work after the fact. Yet there I was, fighting to establish that very thing. What a hypocrite. 4 As research progressed, re-evaluation of my choices within the work led to important discoveries. Becoming more self-conscious of my image making process, I attempted to look objectively at the performative aspect of the work. These actions seemed absurd, such as running back and forth under a slanted ceiling while adorned in a paint-covered prom dress, only to proceed in smashing coffee mugs with a hammer and stuffing yarn into my mouth. Ignorant of the process itself, I had been blind to a key ingredient of myself as artist. Attempting a more objective approach to viewing the work, the completely painted interiors began to speak to façade, alluding to a psychological element. Mental space is constantly changing, unable to sustain itself longer than a fraction of time; the painted interiors began to convey this space as they made shifts in color. There were other studies developing such as that of various relationships between order vs. chaos and control vs. chance, revealing the significance of every choice made and only requiring I acknowledge it. After finally gaining some momentum, it was already time to move the work forward. 5 PSYCHIC UNREST How does one paint a picture of the chaos known as subjective experience? Perhaps we can ask the woman said to be the last person on earth from Wittgenstein’s Mistress, a novel by David Markson that haunted me as I started work towards my second series of self-portraits (Figures 6-10). The chapters ran into each other as the lone voice of the woman rambled through endless pages of colliding statements. Doubtless, her chaotic internal dialogue painted a disturbing image of this aforementioned experience, making a strange but lasting impression on me. My work was undergoing transition and I felt lost between two worlds. Realizing I was nothing but a speck of dust, I sought balance within a cloud of uncertainty. Anxiety soon announced itself as an integral part to my being, with doubt as a leading voice of thought. My previous work had started to move into the realm of the obscured figure, lacking identity while suggesting absurd allegories of self-mocking. Anxiety encouraged the need to obscure the figure even more as my self-search plunged towards heightened absurdity. Fighting urges to work outside of my increasingly claustrophobic studio, I contemplated ways to reduce the elements comprising composition. It was important to cover the wall and floor space, a desire to confuse space I had maintained from the painted tableaus of my previous work. Thinking about image surface and pictoral space, I found excitement in camouflaged moments of tension or when the perceived surface of the image was reduced or flattened. This was the tension I wanted in the new work, as it was a direct reflection of the ambivalence I felt. 6 Maintaining a psychological interest, my attention swayed ever closer to that of the absurd. It was then that I discovered the photographs of Roger Ballen, whose flattened images suggested a confrontation that managed to get inside the existential disturbia most try to avoid. The black and white photographs were unsettling and obscure, as I gained interest in the formal aspects of work from his book Boarding House. His approach to making photographs was unlike any other photographer I had seen as they allowed me to understand the image as made up by objects, or forms. There was a psychological charge to Ballen’s work that I sought in my own, which in turn influenced me to think more about object and figure configuration. As I began the work, I took into account the significance of formal relationships to varying states of mind, as if they could be arranged by form. A strong interest in patterning also emerged as I juxtaposed layers to suggest doubt and create tension, attempting to dissolve the figure in space. The work was shifting from the narrative image closer to that of abstraction, demanding a different kind of attention. As I attempted to displace my body through the uncanny, psychic unrest rose to the surface. However, moments of success are accompanied by those of failure. At first, it was hard for me to see my work as an evolution of thought. The commonalities were muted and awaiting reflection, as I was far too distracted with experimentation. Attempting towards cohesion, I somehow tangled fashion and abjection, suggesting an aesthetic and ideology I did not intend. However, there was continuity within the formal and figurative aspects as I strove to understand self. All work seeks resolve. I was slowly discovering resolve, which came in the form of new work. 7 SHAME The claustrophobia of the studio was overwhelming at this point and I had to get out. Ironically, the first image I made resulted in what seemed to be the inverse of my studio work (Figure 11). Completely concealed and immersed in an open landscape, my body had transformed into a red cocoon, recalling the ghost of Ana Mendieta. Thinking back to previous work, there was a clear evolution towards the absence of my physical body. In regards to wrapping my body in crepe paper, this was not a feat I could achieve alone. The work required assistance from other people, demanding consideration towards collaborators. My husband was an easy choice on the first attempt; however, knowledge of that intimate and somewhat terrifying experience confirmed it needed more thought. After narrowing my options, I ended up at the roots of where it all began, where the shaping took place, with my family. It was at this point that I began to ponder the notion of shame as a hypothesis. Collaborating with family was difficult, especially considering the geographic differences. The process developed as each family member was instructed to wrap me at different times and locations over the span of several months, in sites specific to our histories together. After the wrapping process, which varied in style from person to person, they would then take on the role of capturing the image (Figures 12-15). Through stepping away from controlling every detail behind the camera, I became more conscious of the narratives involved in the process of composing a shared experience. In thinking about this notion of shame, I again referred back to my previous work and the repeating elements that spoke to the psychological element. One thing that stuck 8 out was the repeated act of concealing my face, along with other objects and walls within my environment. In reference to shame, I associated concealment with hiding and embarrassment, thinking about what could reveal itself in concealing my body entirely. The sense of urgency in being contained heightened, for if I moved, the paper would move and destroy the form. After the first image was made and revealed to me, I was astounded at how obscure and abstract the figure was. It became something else entirely, acknowledging an influence from abstraction while at the same time hinting at a grander narrative that involved the interactive process of working with another person. Many things were realized as the images were made. I knew because my selfimage was obscured, I had to maintain a consistency within them that spoke to the idea of identifying the figure as the same thing within the varying environments. The color red became important in pronouncing that identification; not only acknowledging that it is the same figure throughout, but also to isolate itself within or against an environment. The color red also embodies the many emotions associated with it, while containing and isolating the figure to reveal something of itself. The reference to façade appeared again with the wrapped figure, while the scale of the images varied from small and intimate to large and prominent. It was important to identify the work in a varying manner, as each familial relationship played a different and important role. As the work evolved, it maintained a subjective approach to its development and attempted to compose a shared experience with loved ones while adhering to a personal concept. It was through the act of constructing a shared experience that the importance of the greater narrative was pronounced, as it highlighted details encompassed throughout 9 human interaction and personal relationships. This greater narrative came to embody what was missing from the images alone. Including text captions with the images enabled the work to communicate at a more personal level to an audience. While the work stemmed from a subjective place, human relationships are universal and it was important to give the viewer a new experience in response to the work. Through my insistence on including those closest to me in the art making process, it seemed the work could have been intended for them. Sometimes I question my motives, wondering if I felt the need to include family for some kind of acceptance of my decision to pursue art, or if it was intended to build on my personal relationships, giving me closure. Doubts remain as to whether these investigations were able to resolve my intent. Regardless, it was something I needed to pursue for myself. 10 BEING Heightened sensitivity to my surroundings was pivotal to the wrapped series, yet was absent in the images themselves. The work had to progress as I felt obliged to continue investigating the wrapped form. I made various attempts to communicate more of the actual experience through the photographs, supplying instructions to participants and involving another human figure to interact with the wrapped one. There was a psychological tension establishing, but the work was not progressing as I thought it should. How could I communicate what was happening in the present moment through a photograph if the image was merely a momentary reflection of the past? I had been urged previously to think about time-based media but put it off to the side, having felt insecure working with a new medium. However, my current predicament was begging me try something new. Fighting the desire to make another still image, I set out with the lone purpose of making a video. My husband wrapped me once again as I realized maintaining my posture would present a new challenge with a time-based medium. The still images had required less time, with the process ending after a few clicks of the shutter. However, endurance came to the forefront with video as it demanded longer stretches of time and heightened the importance of balance and composure. The paper surrounding me threatened to break with each breath as I struggled to hold the pose. It was an extremely meditative process, trying to maintain oneself in an incredibly vulnerable state. When I reviewed the video, the stillness of the wrapped form against the naturally moving landscape struck me. I had become the audience to an experience I missed 11 completely, reliving a present moment I had been literally blinded to. Unthinking my decisions yet again, I questioned the need to be wrapped. My intent with the wrapped form was to derive the essence of self through absence, but it lacked a true reflection of my person as human. Perhaps it was time to stop hiding. It was then I realized the stillness of the figure alone was enough to communicate the sense of absence I sought. The work has evolved as a reversal of thought, constantly removing elements and attempting to get closer to an underlying truth. The philosophy of Martin Heidegger has been extremely influential in regards to my understanding of existence. Early in my academic career I claimed his notion of Dasein, which I defined simply to be, as essential towards how I exist in the world. It was a notion that seemed to blur the complexity of existence with a simple, sobering concept: to merely exist. Returning to the work, I was urged yet again to reduce it even more. I didn’t need props, paint or crepe paper to communicate something of how I am. Was it not enough to simply be there, dwelling in time and space? It seemed risky to do something so simple, especially considering the previous expectations of my art. For too long I considered the importance of aesthetics as highly significant, overlooking the seemingly banal and the potential it held. With expectations reduced to simply that of faith in my own being, I was relieved of the mental anguish I had prioritized as the intent to my art for so long. I had to let go in order to receive. My work has always concerned the relationship of my body to space. As I set out to work with nothing but the camera and myself, I thought again about the stillness of the wrapped figure against the moving landscape. It seemed simply locking my body into an 12 action or non-action as a self-imposed assignment could function in a similar way (Figures 16-18). Though I was no longer trying to obscure or conceal my body, I was still interested in my role as part of the audience and turned my back to the camera as a video was made. This helped achieve the absence I spoke to earlier, especially when the figure stood still. Space and time overwhelm the subject, weaving around it. The meditative state of mind is still present, offering the viewer to become part of a shared subjectivity. As the work commenced in making itself, a dialogue of various relationships flowered which explored restraint and freedom; presence and absence; desire and discipline; control and chance; subjective and objective experience. A five-minute length for each work provided an ample window of opportunity for chance happenings, as the distance between the viewer and subject presented itself as a space susceptible to interruptions. Having given up complete control to everything other than my own body, I was blind to nature’s voice in the process; receiving it later as a gift when first viewing a piece. The work finally came closer to the experience I sought, communicating transience through movement and sound, moving in waves of natural tension. Nature was guiding the work as my body imposed on its space. It seemed the complexity I strove for previously in art making could be embodied through simplicity. From this simplicity, I am back to a beginning, only this time supplied with the meaningful residue of experience. 13 CONCLUSION Understanding my work as an artist is analogous to understanding my existence as human. There are no simple answers or conclusions to be drawn. There are only the questions that drive experience through the dense fog of uncertainty. Resolve seems to come in the form of irresolution, yet important questions hold potential for resonance and meaning. What I once knew of art making has been transformed through unthinking. Reconsideration has allowed me to confirm my voice and return to the essence of my intent; an essence of being that had been there all along. All it required of me was to acknowledge its presence. Through an evolution of thought, the work has progressed and strengthened, allowing me to better understand what it is to be human. In that regard, I have acquired a better knowledge of who I am as an artist. It is critical to remain conscious of our own identities in relationship to this constantly changing world, while staying in touch with our thoughts and uncovering our true potential. Dwelling in a state of transience, we are constantly in flux. So, the question remains: What next? Having come full circle, there are no finite conclusions to be drawn. The work is unfinished, so long as I exist. 14 FIGURES Figure 1. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 2. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 15 Figure 3. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 4. Untitled, 2010, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 16 Figure 5. The Cold War, 1999, Sandy Skoglund, color photograph, www.sandyskoglund.com (accessed on 5/1/12). Figure 6. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 17 Figure 7. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 8. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 18 Figure 9. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 10. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 19 Figure 11. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 12. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 20 Figure 13. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 14. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph 21 Figure 15. Untitled, 2011, Laura DeAngelis, color photograph Figure 16. One, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still 22 Figure 17. Two, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still Figure 18. Three, 2012, Laura DeAngelis, video still 23 BIBLIOGRAPHY Markson, David. Wittgenstein’s Mistress. London: Dalkey Archive Press, 1988. Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: HarperCollins, 2001. Ballen, Roger. Boarding House. London: Phaidon Press, 2009.