Chapter 17. The Law and Justice

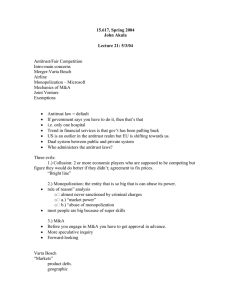

advertisement

1 Chapter 17. The Law and Justice The law should never be mistaken for justice. The people who write the laws, the people who enforce the law, and the people who argue the law may have no conception of justice. They have little more role in deciding what justice is than anyone else. Justice has been viewed in a wide variety of different ways. At the Platonic extreme it has been considered an absolute, which on inspection people innately understand and know. Similarly, many religious conceptions of justice suggest that we can come to know what justice is as God reveals it to us. By contrast, a modern secular view of justice is that it is a system of unconscious rules that emerge as people interact with each other. In all of these conceptions, justice requires thought to understand. Thoughtless laws can easily abridge justice and all laws are continually modified to avoid contradicting justice. Nevertheless, the problem with continually changing laws is that new laws can be more thoughtless and unjust than the ones they replace. There is a danger of making changes in the law too easily. To protect against this danger polities place a great weight on the history of law and make it very expensive and bureaucratic to change the law. In this semester we will see that the Supreme court generally uses the principle of “stare decisis” to defer to earlier precedents rather than to make new law. Similarly legislators make important changes in the law, such as a constitution convention to amend the constitution, face very high voting hurdles. Why do we Need the Law? Because people have different conceptions of how just or unjust our laws are, society must require people to follow certain agreed rules of conduct- in other words, law- regardless of whether they are just or not. The important issue is that laws be followed until they are overturned by a legal process. That legal process is enshrined in a constitution. In the U.S. the focus of the whole judicial system is to ensure that the legal process is followed. Issues of merit are determined at the district court level – often by juries. Any appeals of the jury decision is made on the grounds of violation of legal procedure, not the merits of the case. Time and again in the cases we read this semester, we will find that the appellate and supreme courts may disagree with the merits of a case, but they will focus decisions on simply the technical issue that legal procedure has been followed. What does the Law Cover? If we lived in the Garden of Eden, presumably none of us would need laws. Peoples’ selfishness and acquisitiveness when there are scarcities can be expected to interfere with their sense of justice. While Economics studies ways to optimize our goals given resource constraints, the law sets constraints on behavior. Hume (in his Treatise of 1 2 Human Nature, being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of reasoning into Moral Subjects) believes there are three “fundamental laws of nature”1: (1) The stability of possession. In other words, people have a right to be secure in their papers, persons and effects. (2) Transference of property by consent. People can transfer their property to others and anyone who tries to take it from them without their consent is violating the law (3) Performance of Promises. If you write a contract promising some kind of performance then you must perform according to the terms of the contract. To the extent that government is viewed as fairly promulgating law and enforcing it, it may be viewed as just, even when there are great injustices being done by the law. The Relation between Economics and the Law A key focus of our course is that Law and Economics do not necessarily agree on many of the most fundamental concepts such as competition, market power, the mechanisms for controlling market power, and the basis for government intervention. We will want to understand why the two disciplines have diverged and why they have converged at different times historically. Government and the Law The formal structure of government control over corporations is codified in laws promulgated by the Legislative Branch of government, is enforced by the Executive Branch of government, and is interpreted by the Judicial Branch of government. The Constitution of the United States set up these three branches to keep each other under control by a system of checks and balances. For example, the court system is a part of the Judicial Branch of the U.S. government which is quite distinct from the other two branches, the Congressional and Executive Branches of government. However, the system of checks and balances between the three branches of government have led to agencies and committees that interact with the Judicial Branch. For example, the Executive Branch of the federal government, which is headed by the President of the United States, has a Justice Department which can bring cases before the court system of the Judicial Branch of government. Also the Senate Judiciary Committee which belongs to the Congressional Branch may hold hearings on enforcement of laws by the Executive Branch or the functioning of the Judicial Branch. However, these agencies are quite distinct in their functions. It is useful to see how they have each functioned to contribute to the present legal environment that business faces. A. The Legislative Branch: the Makers of Law There were two ways to control corporations- through their charters and through their treatment as “persons under the law”. The “charter approach” was a method suited to a form of government dominated by a monarch. Treating corporations as people has been a method favored more by a democratic state. 1 F. A. Hayek, Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. U Chicago Press 1967 p. 113. 2 3 1. Charters Before the United States even existed, the king of Great Britain granted corporate charters to large companies such as the British East India Company to develop new colonies. To make such charters worthwhile special privileges and monopolies to trade were granted. The King granted such charters with the expectation that a company was to serve the interest of Great Britain and often restricted how trade was to be carried out. Such privileges and restrictions were among the burdens that the American colonists would rebel against. When the colonists overthrew the power of Great Britain, they nevertheless adopted the institution of corporate charters. However, they were quite restrictive in how these charters were to be used. Corporations were often required to state the purpose they would serve and would be held to that purpose. The charters were often granted for a restricted period of time. They were often restricted from owning each other or having any special legal ties to each other. Sometimes the corporations were given price limitations on what could be charged. Some states held stockholders personally liable for debts of the company. There were many other kinds of restrictions on governance of the company and the ways that they issued stock, the way they paid dividends, and the kinds of records they needed to keep. However, each state issued its own rules. Even to this day, corporations seek the state with the most favorable rules. Sixty percent of incorporations are done in Delaware, even though the headquarters of these corporations are in other states. Because charters could be revoked, corporations had to be careful in the 19th century to serve the public interest as specified in their charters. By the mid nineteenth century charter revocations were frequent. For example in 1832 Andrew Jackson revoked the charter of the Bank of the United States which was owned by the Biddle family of Philadelphia and which had monopolized the banking services for the U.S. government. By the 1870s 19 states had amended their constitutions to allow revocation of charters. However, in the last thirty years of the 19th century the courts began to issue rulings that limited the limits on corporations and corporate property. Some of the most important changes included: 1. Private Corporations as “Persons.” In Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad [118 U.S. 394] the Supreme Court decided that a corporation was a “natural person.” This meant that they were accorded the right, given in the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, to due process under the law. The courts then created the concept of “substantive due process” which proscribed governments from taking property from corporations. As a result and as we will see in the discussion of regulation, it would take extensive legal battling before the courts interpreted the Constitution to give the federal government the authority to limit prices. This ruling had the effect of placing corporations on an equal footing competitively with other private businesses and individuals, such as farms and partnerships (which faced more strict legal restrictions and liabilities). 3 4 2. Redefining the “Common Good.” Rather than defining the purpose of the corporation in terms of what was decided by elected officials, the common good was interpreted more narrowly to be what was in the interest of the Corporation’s stockholders. 3. Eminent Domain. Corporations could take private property with very little reimbursement to those who lost the property. The courts often set the reimbursements at levels favorable to the corporations. 4. Right to Contract. The government was proscribed from interfering with the way Corporations contracted for labor. Today “right to work” legislation continues to be a major legislative agenda item; where enacted it would allow employees to contract with a corporation without going through their labor unions. By the twentieth century charter revocation fell into disuse. Only very recently and in a few limited circumstances have states actually revoked charters for corporations that have failed to carry out their responsibilities under their charters. Nevertheless there are frequent calls, particularly as a result of scandals such as Enron and Global Crossing, for the states to use their chartering authority or for the Federal Government to take over corporate chartering. 2. Congress The Constitution of the United States provides Congress with the power to make the laws for the United States within very important limitations. After the Revolutionary War, the states unified under the weak Articles of Confederation in 1781 which preserved so much power for the States that the finances of the new government fell apart. It was necessary in the new Constitution of 1788 to give more power to the federal government, but an attempt was made to preserve the power of the states and to restrict the new Federal Power. However, once the Federal government was created its powers gradually increased. The Civil War ended any illusion that states would have the ability to withdraw from the Union that had been created. The Constitution gave Congress the authority “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States.” With the help of three key, interpretive cases by the Judicial Branch.2 One key clause of the McCulloch v. Maryland which states “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.”, 4 Wheaton 316 (1819). The police power of the Federal government was enhanced in the cases: Brown v. Maryland, 12 Wheaton 419 (1827); and Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 11 Peters 420 (1837). 2 4 5 Constitution, commonly referred to as the Commerce Clause became a major vehicle for the expansion of federal power within the United States. It read: The Congress shall have power… to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes. While Congress was reluctant to provide new powers to the government except in times of war and economic hardship, the Judicial Branch of government would extend the powers of the federal government simply by interpreting more and more forms of “commerce” to be within the federal government’s jurisdiction. Where conflicts between Federal and State governments existed the Federal law had supremacy over the state law. Congress was very slow to pass new legislation to limit business. It was not until the monopsony and monopoly powers of the railroads made themselves felt extensively throughout the West that governments began to regulate businesses explicitly to limit their market power. Businesses were beginning to merge into Trusts which monopolized industries like Oil, Tobacco, and Sugar. The states initiated some of the first antitrust laws. In 1890 Congress finally passed the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 is the nation's oldest antitrust law. It prohibits various forms of cooperation among competing firms. Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust law states: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal.i To contract, combine, or conspire requires two people or two firms. It does not take much of an agreement to come into violation of this clause if the effect of the agreement impedes competition. Furthermore, the agreement is not restricted simply to decisions about prices or output; it can apply to any aspect of managerial discretion including advertising, merging, contracting, and other managerial tools. Price fixing, dividing up markets, and boycotts are examples of cooperative behavior prosecuted under Section 1 of the Sherman Act. In addition the Sherman Antitrust Act prevents some forms of behavior which are extremely uncooperative. When a firm tries to eliminate its competitors it may come in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act: Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be guilty...ii "Monopolizing" is an activity which is intended to eliminate other firms or potential competitors in a market. Obviously a firm can only monopolize when there is another party to be eliminated. Firms that already have a monopoly are not likely to engage in the kind of behavior prevented by Sherman Section 2. However, dominant firms in an oligopolistic market which use their power to eliminate rivals or even potential rivals are likely to find themselves in violation of Section 2. The Sherman Act has been applied to the interdependent behavior- both cooperative and uncooperative- that occurs in oligopolies, 5 6 not monopolies. The laws made the conduct in oligopoly illegal, not the market structure we call monopoly. Subsequent law and court cases have become more specific about the types of interdependent behaviors that are illegal. The Clayton Act of 1914Clayton Act of 1914 made the following practices illegal: (a) Price DiscriminationPrice Discrimination. With later amendment by the RobinsonPatman Actiii, Section 2 of the Clayton Act stated: It shall be unlawful for any person engaged in commerce, in the course of such commerce, either directly or indirectly, to discriminate in price between different purchases of commodities of like grade and quality.... and where the effect of such discrimination may be substantially to lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce... However, it is still possible to charge different prices to different customers if the difference can be justified by differences in the cost of producing an item. Later, such differentials were permitted to meet a competitor's prices. However, the practice of charging different prices based upon what the market will bear is illegal if it lessens competition. This section has subsequently been amended. (b) Tying and Exclusive Dealing. Tying Tying occurs when the purchase of one good requires that another good be purchased from the same supplier. Exclusive dealing Exclusive dealing prevents customers from purchasing from competitors. Section 3 of the Clayton Act prevents both practices: It shall be unlawful for any person... to lease or make a sale... on the condition... that the lessee or purchaser thereof shall not use or deal in the goods.... of a competitor or competitors of the lessor or seller, where the effect of such ... condition... may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce. A computer firm may exchange the sole right to distribute a product in a geographic area to a franchise that is willing to buy only (exclusively) the firm's computer product. Such a cooperative effort may violate Clayton Section 3 if there are less restrictive ways to accomplish the firm's goal in distributing the product. (c) Acquisitions and mergers of competing companies. Section 7 of the Clayton Act had to be amended by the Celler-Kefauver Antimerger Activ to make the prohibition of horizontal mergers effective. As amended the prohibition reads: No corporation engaged in commerce shall acquire, directly or indirectly, the whole or any part of the stock or other share capital and no corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission shall acquire the whole or any part of the assets of another corporation engaged also in commerce, where in any line of commerce in any section of the country, the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly. Horizontal acquisitions and mergers can be the ultimate cooperative effort, but here such cooperation is directly and indirectly prohibited. 6 7 This prohibition has been translated by the Federal Trade Commission into merger guidelines which indicate the specific market conditions under which mergers will be challenged (see Economist's Tool Box in Appendix 1 to Chapter 11) (d) Interlocking DirectoratesInterlocking Directorates. Section 8 of the Clayton Act prevents directors from serving on the boards of competing firms. A director sitting on the board of two competing firms could facilitate communication and coordination between the firms thus leading to an erosion of competition. The antitrust laws acquire meaning in our legal system through the cases that are brought before the courts based on the laws. For example, in the above quotations of the law, notice how often the following phrase appears: ..."may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce." Court cases provide a set of precedents of situations in which behavior may "substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly". Even more importantly court cases have gradually defined what a "line of commerce" is. In fact, market and product boundaries which are the basis for determining a "line of commerce" are a very important part of the arguments presented in many antitrust cases. Acceptable procedures for establishing these boundaries have gradually evolved through court cases.v A major part of the impact of Antitrust laws therefore comes through interpretations in subsequent litigation. B. The Executive Branch & Independent Agencies: the Enforcers of the Law The Executive Branch consists of a large number of agencies with specific mandates for specialized tasks for intervening in the economy. We will focus here on the antitrust agencies to give a flavor of what the Executive Branch does. There are two federal antitrust agencies- the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission, which was established by the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914.vi The Justice Department goes through the normal appeal channels of the District Court, Appeals Court, and Supreme Court, the Federal Trade Commission has its own procedure. The Federal Trade Commission's appeal procedure must be exhausted before a case ever reaches the courts; this can prove costly in time and money. However, many firms will drag out the appeals process as long as possible when the results of the antitrust actions appear to be going against them. The antitrust agencies design the strategy of enforcement of the antitrust laws. The antitrust agencies have two kinds of remedies for antitrust violations. They can punish individuals for past conduct through criminal penalties criminal penalties or they can alter the structure of a firm through civil suitscivil suits. Civil suits allow injunctions to prevent mergers, acquisitions, or other actions that might lessen competition in the market place. Because changes in the structure of a market are believed to result in changes of conduct, such civil suits have the greatest potential for preventing the reoccurrence of illegal conduct in the future. If the case involves a criminal case, which is an action brought against a specific person for a criminal act that may involve a jail sentence, then it may involve as many as twelve jurors. However, in a civil case, which involves the correction of a right such as a property right, a judge will normally decide the case and the penalties generally involve a financial or property penalty. While civil penalties usually involve punishment 7 8 for past acts, civil actions usually involve prescriptions from future behavior. Both civil and criminal procedures are costly in terms of money and time. While Section 4 of the Clayton Act allows a plaintiff plaintiff (the one who has the complaint and brings the case against the defendantdefendant) to recover legal costs, such recovery only occurs when the plaintiff wins the case. Furthermore, the financial condition of the defendant may prevent the recovery not only of the legal costs but also the recovery of the damages. To avoid such costs a plaintiff and a defendant may elect to settle out of court. Settling out of court confers benefits on a defendant by preventing an undesirable precedent from being set, and by preventing damaging information from becoming public record. It also subjects a firm to less damage to its image and lower damages than those that would be awarded if a trial were lost. Antitrust violations can carry penalties significantly greater than the financial gain that might have been achieved by violating the law. Section 4 of the Clayton Act states: ...any person who shall be injured in his business or property by reason of anything forbidden in the antitrust laws may sue therefor ... and shall recover threefold the damages by him sustained, and the cost of suit, including a reasonable attorney's fee. "Treble Damages" means that the results of collusive effort can be made negative. Nevertheless, because some violators may never be detected, treble damages do not take away all of the incentive to break the law. Managers frequently feel uncomfortable with the antitrust mind set. While managers operate in an atmosphere in which maximizing market share is a desirable goal, few managers are caught announcing their success in achieving greater market share in testimony on an antitrust case. Many goals and values held by managers within the firm, must be modified when managers face the community outside of a firm, particularly the antitrust agencies. Advertising which prevents potential entrants from entering a market may be a wonderful tool in the mind of a manager, but proclaiming such a strategy in an antitrust case would suggest anticompetitive effects and barriers-to-entry. High profitability may be the ultimate goal of a manager's strategy, but "excessive" profits in an antitrust case may provide evidence of market power. Market share has a close relation to the measures (concentration and the Herfindahl index) which are used by the federal agencies as measures of market power which might help to convict a firm of an antitrust violation. A manager must learn the language and the point of view of the government, must design a strategy for complying with the antitrust law, and must effectively direct a firm to conform to this strategy. In fact a manager may have to learn to argue different points of view. For example, in trying to merge with another firm, a manager might wish to define market boundaries very narrowly so that the firm will not be viewed as a competitor of its proposed partner in "any line of commerce." On the other hand, such narrow market boundaries might make the market appear to have a high concentration ratio and the firm appear to have significant market share which could be interpreted as significant market power. A manager must also keep abreast of continuous evolution of the law. In some areas such as the legality of vertical territorial restraintsvii, tying, and mergers, the courts 8 9 have reversed themselves on what is legal behavior. Congress has written amendments to the antitrust laws and has used its budget making authority to change antitrust enforcement efforts. Each new president alters the policy and enforcement efforts of the antitrust agencies. C. The Judicial Branch: the Interpreters of the Law 1. The Hierarchical Structure of the Courts The court system consists of a hierarchy of three levels of courts. Court cases usually enter at the District Court level, which is the first step of the Judicial hierarchy. Flood v. Kuhn 316 F. supp. 271 (1970) Such cases involve a plaintiff, who brings the case against a defendant. Typically a case will be named with the plaintiff’s name first and the defendant’s name listed second. So, for example, if we read we know that Flood is the plaintiff and Kuhn is the defendant. By the way, the “v.” stands for “versus. We know the case was argued in 1970 at the district court level. We can find the case at 316 F. supplement 271 in 1970. This case happens to be the case that made baseball’s reserve system unlawful, and we can go to the supplement which contains the rulings of the judges in this case. Whoever loses at the District Court level can appeal the case and is referred to as the appellant. The party against whom the appeal is brought is called the respondent or appellee. The appellant’s name now appears first and appellee’s name appears after the “v.” The Appeals Court (Court of Appeals or Appellate Court) grants certiorari (“to make sure” in Latin) if it decides to take the case. In the Appeals Court, no new evidence is provided on the case. The only issue is the question of whether or not due process was followed in the lower court. Due process requires fairness in the procedures used in a court such as fair hearings, adequate notice of deadlines and court dates, impartial officers, a high standard of evidence, recording of findings of law, and opportunities for appeal. Due process concerns only the procedure that was followed in the District Court, not issues of merit. The Supreme Court is at the top of the hierarchy in the court system. The loser in the Appeals Court may appeal to the Supreme Court. Once again, the only basis for such appeal is violation of due process. The Supreme Court does not handle new evidence nor does it supposedly address the merits of a case. When the court does appear to make decisions on the merits of an issue, it comes under criticism, even from the justices themselves as in the Gore v. Bush case. Generally a Supreme Court case is reported with all earlier court actions. Following is the citation for one of the most important antitrust cases that will be read: 9 10 U.S. Supreme Court STANDARD OIL CO. OF NEW JERSEY v. U S, 221 U.S. 1 (1910) 221 U.S. 1 The “U.S.” in “221 U.S. 1” tells us that the case went all the way to the Supreme court. Standard Oil is listed first so that it is appealing the earlier court (Court of Appeals) judgment. In private suits the court hierarchy is strictly adhered to. However, when the government brings a case, there may be an important exception. Often government agencies set up procedures or hearings that people take issue with. In such cases, the District Court may not be involved and a case may go directly to the Appeals Court to examine whether or not due process has been followed. Nevertheless, some cases involving government agencies do go through District Courts. As we shall see, the Supreme Court has increasingly deferred to the judgment of government agencies. Whether going through District Court or not, the Supreme Court’s role is to ensure that due process has been achieved in the legal system, not to judge the merits of the issues. The Supreme Court does not speak with a unanimous voice. The Supreme Court Justices often are at odds with each other and several books have been written by court watchers describing the dynamics of the Supreme Court on important issues. At the end of the majority opinion in a Supreme Court case, dissenting opinions from the majority opinion are presented. Besides sharpening the understanding of the majority position, the dissenting opinions are particularly important if the minority of justices is large. For example, if four justices agree to one dissenting opinion, it might take only one replacement of a Supreme Court judge to lead to a reversal of the original decision. However, even if the balance of justices changes, they are very reluctant to reverse earlier decisions. Such reversals lead to uncertainty and confusion about the law which can undermine the legal system. So the legal system, embodied in precedents set by the Supreme Court (and sometimes lower courts), intentionally slows down the rate at which laws are changed the Supreme Court. ================================================================ EXAMPLE: See If You Can Tell What Happened Just By Reading The Title of a Case 10 11 Here is another important Antitrust case. Just by looking at the title of this case you should be able to tell what happened to the case as it went through the court hierarchy: U.S. Supreme Court U. S. v. SOCONY-VACUUM OIL CO., 310 U.S. 150 (1940) 310 U.S. 150 UNITED STATES v. SOCONY-VACUUM OIL CO., Inc., et al. SOCONY-VACUUM OIL CO., Inc., et al. v. UNITED STATES. Nos. 346, 347. Argued Feb. 5, 6, 1940. Decided May 6, 1940. Notice something funny about the order of the names? Let’s see if the summary at the beginning of the Supreme Court decision is helpful: Respondents1 were convicted by a jury2 (United States v. Standard Oil Co., D.C., 23 F.Supp. 937) under an indictment charging violations of 1 of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act,3 26 Stat. 209, 50 Stat. 693. [310 U.S. 150, 166] The Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and remanded for a new trial. 7 Cir., 105 F.2d 809. The case is here on a petition and cross-petition for certiorari, both of which we granted because of the public importance of the issues raised. 308 U.S. 540, 60 S.Ct. 124, 84 …The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reversed and that of the District Court affirmed. It is so ordered. The change in the order of the government and Socony shows that the District Court judgment against Socony was reversed (i.e. “thrown out”) by the Court of Appeals. But the information in the summary shows the Supreme Court reversed the action of the Court of Appeals. Notice that the Appeals Court here is cited as “7 Cir,” which stands for the “seventh circuit” Court of Appeals and identifies which specific Appellate Court is involved. This is the kind of citation you should expect for an Appeals Court, as distinct from the “U.S.” that appears on Supreme Court Cases. At the end of the case the dissenting opinions are presented. ================================================================ 2. Interpretation of the Law Laws must be applied to the facts of a specific case. The court system is set up to make such interpretations. Unfortunately, such interpretations generally occur after, not 11 12 before, events occur. Only after someone believes that a law has been violated and has sued for some form of redress is it precisely known how the law applies. Even then a court may not resolve a case but will fail to take it or decide it upon a technicality that avoids the fundamental issues raised by a case. The most important aid to the interpretation of cases is the past history of cases to which the law has already been applied. In Latin stare decisis means the courts abide by past precedents set in earlier court cases. To make this system work it is necessary to have law reporters which index the salient features of earlier cases and record how the earlier cases were decided. It is also necessary to have such information readily available. With the internet, several different reporters provide cases for free (eg. findlaw.com). Lawyers uses these sources of information on legal precedents to craft a story which makes their “case.” The story generally presents the evidence required by a law or legal precedents in a way that logically leads to a conclusion about the guilt or innocence of the defendant in the case. A lawyer’s skill depends centrally on the ability to hunt down the strongest possible legal precedents that fit the fact situation in a case. Ironically, strong legal precedents often are the Supreme Court cases where (a) a conviction has been made on very weak, borderline, indirect, or disputable facts or (b) a conviction has been overturned even though the strong facts of a case seem overwhelmingly to indicate guilt. Since precedents usually differ significantly from the fact situation of a lawyer’s case, the lawyer must be able to argue the applicability of any precedent that the lawyer uses in a “brief” on a case. Besides choosing strong precedents a lawyer must find evidence with which to back up the lawyer’s arguments on a case. In applying the law to a given situation a lawyer faces the fundamental problem of determining what “the facts of the case” might be. There are many forms of evidence that the court may not allow to be used in a case: immaterial evidence to a case may not be permitted in order to avoid slowing a court case down evidence which is hearsay- i.e. information not directly witnessed but heard from someone else- may be inadmissible in a court proceeding because it is too indirect and fallible. Evidence coerced through misrepresentation, ignorance, threats or torture is unacceptable because people may be willing to say anything to relieve the stress of a circumstance. These are only a few of the kinds of information that a judge might prevent from prejudicing the outcome of a case. The court is attempting to set a high standard for the quality of the facts that are used to bolster a case. The prosecutors or plaintiffs who bring cases have different standards of proof that they must meet. In cases such as capital punishment where the consequences are severe, the standard of proof is set “beyond a reasonable doubt”, which is an extremely 12 13 difficult standard to meet. A prosecutor must not only try to find a fool proof explanation of the facts, but must be able to rebut any plausible alternative explanation that the defendant might make. On the other hand, many civil cases involve a standard that requires only “a preponderance of the evidence.” Under this standard, a reasonable interpretation of the facts may be enough to win a case. For example, it was not inconsistent that the football player, O.J.Simpson, was convicted in a civil case involving the murder of his ex-wife while not being convicted in a criminal case. The Civil Case required only a preponderance of the evidence while the criminal case required “beyond a reasonable doubt.” A judge has the responsibility to educate a jury about the differences between these different standards of proof. Particularly in the antitrust cases, the law typically sets out what must be proved in a case. If the law specifically prohibits a type of behavior then that behavior is called a per se per se violation of the law. The only issue is whether there is enough evidence to show that such behavior occurred. However, in 1911 the Supreme Court established a concept referred to as the rule of reason rule of reason in its Standard Oil judgment.viii Some violations require a rule of reason to be applied in which the effects of an action must be weighed. The rule of reason standard is a much more difficult case to make both for prosecuting and defending attorneys. The biggest problem with the rule of reason is that it may not be possible in advance to determine what is legal and what is not legal. When a firm goes to court and the rule of reason standard is applied, the issue becomes more than just the evidence to prove a firm committed illegal behavior. Under the rule of reason, the court must also weigh whether the behavior is illegal in light of the firm's intent and other mitigating circumstances. Predicting the court's judgment is not a game a manager can hope to play very successfully. Some decisions by a manager may simply purchase a lottery ticket with respect to future antitrust litigation. Because the antitrust laws are evolving and involve after-the-fact judgments which are inherently unpredictable, a firm often is left with uncertainty about what behavior is permissible and what is prohibited. i. 26 Stat. 209 (1890); 15 U.S.C., Sec. 1-7 ii. See previous footnote iii. 49 Stat. 1526 (1936); 15 U.S.C. Sec. 13. iv. 64 Stat. 1125 (1950); 15 U.S.C. Sec. 18 For example the case , U.S. v. E.I. duPont de Nemours & Co. (351 U.S. 377 (1956) establishes cross price elasticities as a basis for defining market boundaries. v. vi. vii. 38 Stat. 717 (1914); 15 U.S.C. Sec. 41-58 The Supreme court has reversed itself on the issue of 13 14 vertical territorial restraints, setting down a tough precedent in the Schwinn case and reversing itself later in the Sylvania case. viii. Standard Oil Company of New Jersey v. United States 14