Study Questions for Philosophy 1000f Final—Fall 2009 Philosophy of Mind: I.

advertisement

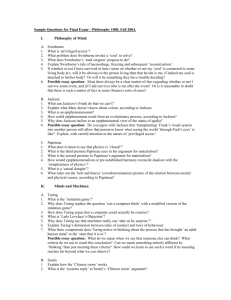

Study Questions for Philosophy 1000f Final—Fall 2009 I. Philosophy of Mind: A. Gertler 1. Why does Gertler think our ability to imagine or conceive something is a reliable test of whether it’s ‘really’ possible? 2. Why does Gertler think it’s OK to rely on thought experiments even though they can lead us astray? 3. Explain Gertler’s thought experiment concerning having pain without a body. What does she think it shows? 4. State the qualified version of premise 2 of her argument that Gertler defends. 5. What is Gertler’s definition of ‘the physical’? 6. How does Gertler define ‘pain’? 7. How does Gertler claim our concept of ‘pain’ differs from our concept of ‘water’? 8. Why does Gertler think that a physicalist must deny that any significantly different form of (alien) life can experience pain? B. Jackson 1. What can Jackson’s Frank do that we can’t? 2. Explain what Mary doesn’t know about colour, according to Jackson. 3. What is an epiphenomenonon? 4. How could epiphenomena result from an evolutionary process, according to Jackson? 5. Why does Jackson incline to an epiphenomenal view of the status of qualia? 6. Possible essay question: Do you agree with Jackson that ‘transplanting’ Frank’s visual system into another person will allow that person to know what seeing the world ‘through Fred’s eyes’ is like? Explain, with careful attention to the nature of ‘privileged access’. C. Carruthers 1. Why does Carruthers think we don’t need to appeal to non-physical goings on to explain what goes on in the physical world? 2. How does Carruthers use Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to explain the possibility that we might know about a mental event without knowing about the identical physical event? 3. Why is the ‘greenness’ of after images not a convincing reason to deny that after images can be brain states even though brain states aren’t ever green? 4. What sort of knowledge is it, for Carruthers, to know what having a sensation of red is like? 5. How does Carruthers’ answer to 4 help to explain why we can know a lot (perhaps even everything) about the brain states that are involved in a sensation of red without knowing what having that sensation is like? II. Minds and Machines: A. Turing 1. What is the ‘imitation game’? 2. Why does Turing replace the question ‘can a computer think’ with a modified version of the imitation game? 3. How does Turing argue that a computer could actually be creative? 4. What is ‘Lady Lovelace’s Objection’? 5. Why does Turing say that machines really can ‘take us by surprise’? 6. Explain Turing’s distinction between rules of conduct and laws of behaviour. 7. What three components does Turing notice in thinking about the process that has brought ‘an adult human mind’ to the ‘state that it is in’? Possible essay question: What do we mean when we say that someone else can think? What criteria do we use to reach this conclusion? Can we mean something entirely different by ‘thinking’ than just meeting these criteria? How could we learn to use such a word if its meaning reaches far beyond what we can observe? B. Searle 1. Explain how the ‘Chinese room’ works. 2. What is the ‘systems reply’ to Searle’s ‘Chinese room’ argument? 3. What is the ‘robot reply’ to Searle’s ‘Chinese room’ argument? Why does Searle think it’s so obvious that there is no ‘understanding’ involved in the ‘Chinese room’ system? 5. Possible essay question: Discuss whether and why Searle’s argument that mere ‘simulation’ of understanding does not constitute understanding succeeds or fails. Is the ‘Chinese room’ a mere simulator of understanding, in the same way that a computer program modeling a hurricane merely simulates the hurricane? How is it similar—and how does it differ? III. Personal Identity: A. Locke 1. What is Locke’s first objection to the ‘identity of the soul’ account of personal identity? 2. What makes something the same animal, from one time to another, according to Locke? 3. What does Locke mean by ‘person’ here? 4. In what does personal identity consist, according to Locke? 5. Why do the interruptions of consciousness that we experience raise a problem for any ‘same substance’ view of personal identity, according to Locke? 6. How does Locke argue that he (regardless of what substance is involved) could be the same person as someone who witnessed Noah’s flood? 7. What cases show (for Locke) that we really do regard a ‘distinct and incommunicable consciousness’ as constituting a different person? B. Reid 1. What is the ‘water of Lethe’ that Reid mentions? 2. Why does Reid believe that identity (of things known to exist at different times) supposes ‘uninterrupted continuance of existence’? 3. Why does Reid think the idea that persons have ‘parts’ is ridiculous? 4. What does ‘remembrance’ do to back up Reid’s view of identity as consisting in the ongoing existence of a permanent self? 5. Why does Reid reject the claim that remembering an action is what makes me the one who did it?’ 6. What kind of evidence do we use to determine the personal identity of others? 7. Possible essay question: If all we are aware of is our particular acts of thought, how can (could) we infer from that awareness that there is a single continuing thing that ‘produces’ these acts of thought? C. Dennett 1. What is Yorick? What is Hamlet? 2. Why does Dennett think ‘Where Yorick is, there I am’ is a bad answer to the question, ‘Where am I’? 3. What is Dennett’s ‘point of view’, after the operation? What view of ‘where we are’ does this notion underwrite? 4. What happens to Dennett’s point of view when his brain’s link to his distant body breaks down? 5. What is ‘Hubert’? 6. Possible essay question: Would there be a clear answer to the question, which is Dennett, if a separate body were found for each of the two parallel ‘brains’ that are now taking turns operating his present body? Discuss, considering some of the arguments we’ve considered regarding personal identity. IV. Freedom and Determinism: A. Ayer 1. What is Dr. Johnson’s view of the issue of freedom and determinism? 2. Why does Ayer find Johnson’s position unconvincing? 3. Why does Ayer think that doubts about the possibility of a fully deterministic causal explanation of action don’t ‘give the moralist what he wants’? 4. Why does it seem that a causally determined agent doesn’t differ significantly from an agent who is constrained, like a keptomaniac? 5. What is Ayer’s answer to the view that we don’t differ significantly from those whose actions are constrained? 6. Possible Essay Question: Do you agree with Ayer, that to be free is really compatible with being caused, and only rules out certain kinds of causes? Or do you agree with Chisholm and d’Holbach, who believe that freedom requires being, in some sense uncaused? Consider the arguments on both 4. sides and explain why you find one side convincing & the other mistaken. B. Stace 1. What is the difference, according to Stace, between the examples of free acts and of unfree acts? 2. How does Stace justify holding someone responsible for their actions even if they are determined to do them? 3. What would follow, according to Stace, from supposing that “human actions and volitions were uncaused”? C. d’Holbach 1. How is the will ‘necessarily determined’, according to Holbach? 2. Why does the fact that, on being told the water is poisoned, a thirsty man can refrain from drinking, not show that the man is free to drink or not to drink? 3. What view of the will has brought about the ‘errors of philosophers’ regarding free agency, according to Holbach? 4. What factors does Holbach declare the actions of man to be ‘necessary consequences’ of? 5. Why does our ability to do as we choose not demonstrate that we are free, according to Holbach? 6. What are the factors involved in human choice that (mistakenly) ‘persuade him (man) he is a free agent’? D. Chisholm 1. Explain how determinism about our choices makes it hard to understand how responsibility is possible. 2. Explain how regarding our choices as undetermined and arising from mere chance makes it hard to understand how responsibility is possible. 3. What other premise does Chisholm say we need to add to “If he had chosen to do otherwise, then he would have done otherwise” before it will follow that “He could have done otherwise”? 4. What is transeunt causation? 5. What is immanent causation? 6. Where does Chisholm think we get the notion of ‘cause’? 7. What ‘prerogative’ generally attributed to God does Chisholm ascribe to us? 8. How does Chisholm explain his idea of motives that merely incline, without necessitating? E. Frankfurt 1. What is the principle of alternate possibilities? 2. How does Frankfurt distinguish the principle of alternate possibilities from the view that coercion is incompatible with responsibility for one’s actions? 3. Describe the difference between Frankfurt’s examples, Jones2 and Jones3. 4. How does Frankfurt’s Black ensure that Jones4 does as Black wishes? 5. Possible Essay Question: Do you agree that Frankfurt’s Jones4 is responsible for what he does, so long as Black does not actually step in to force him? Explain what this implies about the principle of alternate possibilities. Is there any sense in which Jones4 still has some kind of alternative open to him? V. Morality and Egoism: A. Feinberg 4. What is psychological egoism? 5. Outline the first argument for psychological egoism that Feinberg considers. 6. Why does Feinberg reject the first argument for psychological egoism? 7. Why does Feinberg think that Lincoln’s tongue-in-cheek excuse for his altruism in saving the piglets is really incoherent? 8. What makes a motive selfish or unselfish, according to Feinberg? 9. Outline the argument for psychological egoism that is based on ‘self-deception’. 10. Possible essay question: Why does Feinberg object to the ‘linguistic proposal’ version of psychological egoism? Do you agree that such a re-arrangement of how we choose to speak would be a silly thing to accept? B. Rachels 1. What is the difference between ethical egoism and psychological egoism? 2. What does Rachels call the ‘common sense’ view of the requirements of morality? 3. What does an ethical egoist hold? 4. What does Rachels say is wrong with the first argument for ethical egoism? What is Ayn Rand’s principal justification for ethical egoism? What makes the third approach to justifying a form of ethical egoism very different from the first two? 7. Why does Rachels think the argument claiming to show Ethical Egoism is inconsistent fails? VI. Ethical Problems: A. Nussbaum 1. Explain one reason that some of Nussbaum’s students give for refusing to criticize female genital mutilation (FGM). 2. What is ‘general cultural relativism’? 3. What are three of the differences Nussbaum cites between FGM and ‘dieting and body shaping’ in North America? 4. What is Yael Tamir’s general objection to feminist concerns about FGM in the United States? 5. What is Nussbaum’s reply to Tamir’s claim that concern for female sexual pleasure serves the interests of men? 6. Possible essay question: Are the facts that FGM is generally illegal even where it is commonly practiced, that it is widely opposed by many even in groups where it is demanded, and by women who nevertheless consent to it for their children because they accept their husband’s authority on the matter, important to the question of whether FGM is a legitimate cultural practice or a violation of young women’s rights? Do they make a substantial addition to the reasons we have, as outsiders, for opposing it? B. Singer 1. What is Singer concerned about in the opening of this essay? 2. Singer’s argument begins with a simple observation, that ‘suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad’. What is the next principle that his argument turns on? 3. What is the ‘qualified’ (or ‘more moderate’) version of Singer’s principle that he focuses his argument on? 4. What justification for focusing on the local in our ‘helping’ behaviour does Singer consider? What changes in the world undermine this justification? 5. How does Singer answer the suggestion that it may make a difference, that there are other people who are also in a position to help? 6. What is Urmson’s account of the usual line we draw between acts of duty and acts of charity? 7. What is Singer’s response to this version of the line? 8. Possible essay question: Singer’s principles (both the strong one he is inclined to accept and the somewhat weaker one he promotes as perhaps more acceptable) demand a very substantial change in most of our lives. Do you think that moral reasonings like these can justify such drastic actions? (What do you think of the quotation from Aquinas that Singer uses here?) Do you agree that moral principles should be blind to such issues? Discuss. C. Rachels 1. What is the difference between active and passive euthanasia? 2. Why does Rachel suggest active euthanasia may well be preferable, in some cases, to passive euthanasia? 3. Why does Rachels think allowing someone to die by ceasing treatment of some kind really is the intentional termination of a life? 4. Why does Rachel think that the fact that most cases of killing are clearly morally worse than most cases ‘lettings die’ does not show that killing in general is worse than letting die? 5. Rachels claims that not doing something is a kind of action in its own right. What does this imply for the distinction between killing and letting die? 3. Possible essay question: Do you agree with Rachels that Smith (who drowns a child) and Jones (who merely watches the child drown) are equally bad and equally wrong to do as they did? 5. 6.