Inter-personal

advertisement

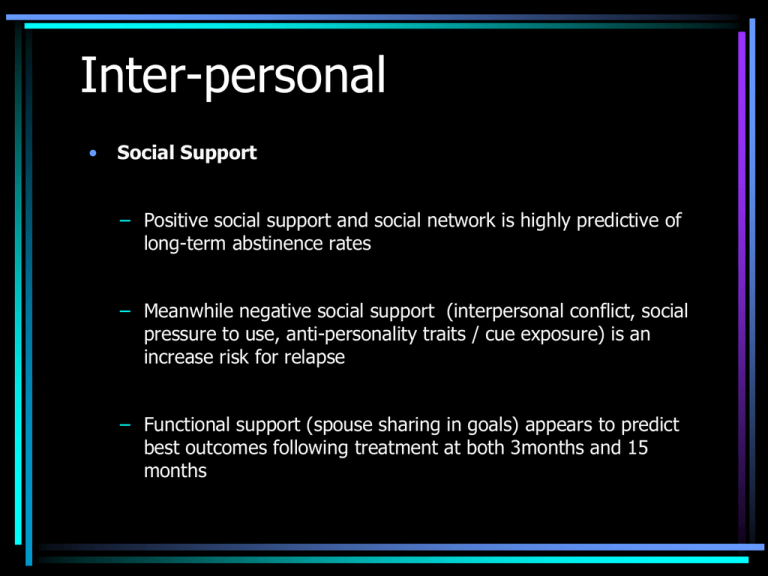

Inter-personal • Social Support – Positive social support and social network is highly predictive of long-term abstinence rates – Meanwhile negative social support (interpersonal conflict, social pressure to use, anti-personality traits / cue exposure) is an increase risk for relapse – Functional support (spouse sharing in goals) appears to predict best outcomes following treatment at both 3months and 15 months Craving • According to Marlatt and Witkiewitz(2005) coping is the most widely studied, but misunderstood concept in the addictions field • Craving is both the physical and psychological and is has been married to the notion of loss of control • Research has disconfirmed loss of control hypothesis Craving (cont.) • Research has also shown that there is a lack of strong association between subjective reports of craving and relaspe. • However, the correlates and underlying mechanisms of craving may still predict relaspe • Thus Marlatt et al. 1999 distinguish between an urge to use from that of a subjective desire to use (which is closer to what they understand as craving) Inter-personal • Social Support – Positive social support and social network is highly predictive of long-term abstinence rates – Meanwhile negative social support (interpersonal conflict, social pressure to use, anti-personality traits / cue exposure) is an increase risk for relapse – Functional support (spouse sharing in goals) appears to predict best outcomes following treatment at both 3months and 15 months Toward the Future: Linear to Dynamic and Multidimensional Models • Need for greater understanding What are we learning? Witikiewitz and Marlatt, 2007 Richard Rosenthal – Staying in the Action • Modern day psychoanalyst, psychiatrist, has been treating gamblers and substance abusers for twenty-years. • Greatly responsible for the DSM criteria of the pathological gambler. • Although trained in psychoanalysis, largely studies the process by which gambling and addiction continues and how to go about treating it. Rosenthal and the Gambler’s Defenses • For Rosenthal, treatment of the pathological gambler lies in the understanding, of how these five defense mechanisms: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. • Omnipotence Splitting Idealization/devaluation Projection, and Denial Interact and help the gambler control his/her inner and outerworld(s), although eventually leading to their demise. Omnipotence: • Refers to feeling of being all powerful, which is a direct defense against feelings of helplessness. • This is a quality found in a great deal of gamblers and is exempflied in their wishful thinking. • I will win because I have to win or I can will myself to win (despite the house odds). Splitting: • Is a defense mechanism whereby the gambler thinks himself/herself to be two separate people. • One is all good: the “winner,” and the other, all bad: the “loser.” Hence, the gambler oscillates between these two personalities types. • One hand, they can act all powerful whereby they seek to try to control others, thus, repressing the loser into the background. Idealization and Devaluing • Essentially, the idea of controlling others is seen in either, I idealize you, or I devalue you. – Thus, as much research points out, we see why gambler’s appear to have problems with intimacy, because the relationship is based on. . . Projection • Process of casting your feelings, thoughts, judgments onto somebody else. • Hence, the gambler routinely goes about controlling his inner world by devaluing/idealizing others. • He or she can then deal with the division with themselves (splitting, good or bad), but never really perceiving that it is them who are bad and good. DENIAL • Or that people themselves can be bad or good, a milestone that the self usually negotiates between the age of 0 – 6. Rosenthal and Treatment • Ultimately, Rosenthal suggest that successful therapy hinges on helping the client realize that they are employing the latter defense mechanisms. • Not to mention how they are related to current gambling binges, and possibly how and why such defenses originated in the first place. Rosenthal and Treatment • The question maybe asked then, “How does the therapist go about bringing these defenses to the clients awareness . . . • The answer is simple, the patient will try to deceive the therapist, idealize him or her, or devalue him/ her, thus projecting their good and bad onto to him or her. • Hence, learning to hold such projections, while equally learning when to help the client peel away their defenses, is key to assessing the role that gambling plays in the client’s life, and why there is a need to feel omnipotent in the first place. Rosenthal and Further Insights: Staying in the Action • Most recently, Rosenthal has brought attention to the issue of dry drunk syndrome and this operates in the gambler; a terms he calls “staying in the action.” • While it is know that most substance abusers have to remain abstinent, it is a near impossibility for gambler’s to not indulge in the use of money, similar to eating disorders. • Thus, this poses a risk for the gambler as they are somewhat still involved in the action (at least when it comes to money). Staying in the Action: I’m Not Talking about Money. • And yet, using money is not the only way in which the gambler stays in the action. • As Rosenthal’s clinical research makes clear, and suggests, that there are many ways for the gambler to take risks, or remain in a gambling mind-set, without making a bet. • Examples of staying in the action 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Mind Bets Success Playing with Reality Covert gambling Lying, cheating and stealing, and; Switching addictions Staying in the Action: Through the Guise of Switching to another Addiction. • The concept of dual addiction is not new, but Rosenthal suggests that a dual addiction for the gambler might not be the case. • Essentially, their supposed co-addiction, may actually represent gambling phenomena or an unconscious or covert way of staying in the action. Switching Addictions: One gambler stated, • After a period of individual therapy and regular attendance at Gamblers Anonymous, Mr. A appeared to have turned his life around. He abstained from gambling, which no longer seemed attractive, and his old debts were being paid off. He had remarried (his first wife divorced him because of his gambling), and claimed he and his wife were happy. His career had gone in a new direction and he was doing even better than before. He worked hard, but got satisfaction from his work. His employer and clients praised his accomplishments, and he was rewarded with frequent bonuses. By all accounts he would be considered successful. • What was wrong? With a great deal of embarrassment, he confided that he had begun frequenting prostitutes. He attempted to rationalize his behavior by telling the therapist that his sex drive was stronger than his wife's, and that she had been less available for him recently because of their different work schedules, and because of her involvement with her ailing mother. His turning to prostitutes, he said, was "quick and easy." • As he continued talking, the self-deception became obvious. If all he wanted was sexual gratification, he knew a number of women willing to accommodate him. He was a good looking, rather charming and outwardly confident young man, and women were sometimes quite forward in indicating interest. They did not even seem to mind that he was married. However, he rejected any and all such opportunities, preferring instead to seek out prostitutes on the street. • Such assignations were anything but "quick and easy." He experienced enormous anxiety that the prostitute would give him AIDS or some other disease which he would then pass on to his wife, or that the prostitute would turn out to be a policewoman and he would be arrested. In addition, he was certain that if his behavior became known, his wife would leave him and his career would be ruined. It dawned on him that he was gambling, and that the more he engaged in this behavior, the more certain he was to lose. – Why, he then asked, when he found a prostitute who appeared "safe," would he not go back to her, but would insist on trying someone different each time? • Obviously he either wanted to lose, or was excited by the risk of jeopardizing everything and escaping unharmed. • Mr. A then recognized that the feelings he had while looking for prostitutes were identical to the feelings previously experienced gambling. He not only had the same "rush," but the compulsive aspects were the same. He would find himself preoccupied by it while at work, inventing excuses for driving home through neighborhoods where there were streetwalkers. The anticipation, and the guilt afterwards, and the need to lie about where he spent his time and money, all reminded him of his previous gambling. Opinions Please? • What do folks think about this case? • Is it gambling or is it a sex addiction? Switching Addiction and Treatment • For Rosenthal, gambling and his sexual compulsion can be fused, which is not an uncommon occurrence. • However, when looking at addiction this way, the therapist needs to be sure that the phenomena he/she is hearing is actually what is happening. • Thus, making treatment easier, despite the complexity in treating an addiction switcher. Switching Addiction and Treatment • Essentially, at the core of the behavior was risktaking, and more pertinently, reliving / reenacting former gambling behaviors. • As such, these behaviors needed to be pointed out, investigated, and brought to light, whereby staying in the action is understood fully by both client and therapist alike. Lying, Cheating, Stealing • A second way gamblers stay in the action is through, lying, cheating, and stealing. • For some pathological gambles, lying, cheating, and stealing are the heart of their addictive behavior. • Even after maintaining abstinence, LCS, may still frequent the gambler’s mindset. Confronting Lying, Cheating, Stealing • Hence, sometimes the slightest transgressions on part of the client need to be investigated. • Because part of the pathological gambler’s game is to have the therapist collude with them. • And in this collusion, the gambler wants them to accept their dishonesty, as something that cannot be changed. (At least I don’t gamble, right?) • Rosenthal suggests, that by not confronting the gambler on such matters, the client is unconsciously devaluing the therapist, themselves, and the work they have done together. Case of Magazine theft. . . • Mr. D took a magazine from the waiting room and brought it into the session with him, and then, afterwards, while driving home, realized he still had it with him. Actually he had wanted to finish reading an article, so his forgetting, although not conscious, nevertheless served a purpose. He had not thought of asking if he could borrow it, because the therapist might say no, and besides it would have made him aware of his dependency on another person, something he went to great lengths to avoid. He did have a momentary thought that he should go back and return the magazine, but "put it out of (his) mind.” • The following week he forgot to bring the magazine with him for his appointment. He intended to mention it but started talking about something else, and it was again forgotten. He was shocked when the therapist brought it up halfway through the session, and referred to it as a kind of stealing. Mr. D became very defensive, and argued that everybody did things like that, but then realized that he had been feeling particularly uncomfortable about coming for the session, and had not known why. • Nevertheless, he persisted in trying to trivialize the incident, and could not accept the therapist's contention that it was something for them to examine in the session. It was only later that he could admit to other "omissions"—obligations that were forgotten, bills he ignored, promises he failed to keep—a pattern of lying and cheating that he had not consciously recognized. By stealing the magazine, the patient was gambling that he could get away with it. • He was also protecting, and trying to keep out of the therapy, a part of his personality that believed these kinds of activities were all right. This included his secrecy and sense of entitlement. Only when this was acknowledged and dealt with was there any chance of recovery. Primitive Avoidance and Case of the Magazine Theft. • According to Rosenthal, this example illustrates not only how one little lie or omission can lead to another, but the kind of "primitive avoidance" so common among pathological gamblers. • Hence, uncomfortable realities can be just put out of mind, or "shoved under the rug.” But, the therapist cannot let little things like this go, because if they do, they actually are enabling covert behaviors to continue possible leading to full blown relapse. • Thus, Rosenthal suggests that the pathological gambler must develop, or reestablish, an internalized value system based on honesty and integrity. Guilt and Staying in the Action • And the only way to help the gambler deal with their staying in the action behaviors, is to have the gambler take responsibility for their dishonesty. • Hence, as evidenced in a great deal of psychodynamic theories presented, the gambler needs to dispel their guilt. • Which is done by not decreasing their discomfort over their guilty actions and allowing them to get away with it, but to actively challenge it and get to the bottom of why the guilt is their in the first place. Guilt and Staying in the Action • One of the major reasons for intractable or unrelenting guilt is the continuation of some harmful behavior, however covert, subtle, or rationalized. • The first step toward self-forgiveness is an acknowledgment of change. In other words, being able to say “I used to do such-and-such. I don't do that any more.”