ADVOCATING FOR ARTS IN EDUCATION: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY Kristi Morales-Scott

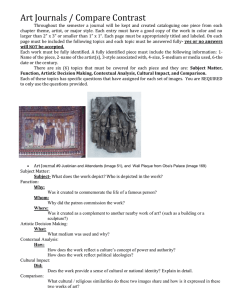

advertisement