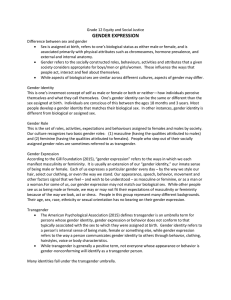

BREAKING THE BINARY: ADDRESSING HEALTHCARE DISPARITIES WITHIN SACRAMENTO’S TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY A Project

advertisement