Marketing AIDS prevention The differential impact hypothesis versus identification effects

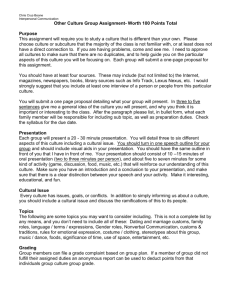

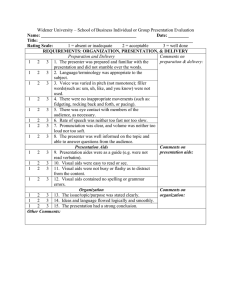

advertisement

Marketing AIDS prevention: The differential impact hypothesis versus identification effects Michael D. Basil Assistant Professor Department of Mass Communications, University of Denver, 2490 S. Gaylord, Denver, CO 80208 Phone (303) 871-3984, FAX (303) 871-4949, email: MBASIL@DU.EDU and William J. Brown Professor and Dean College of Communication and the Arts Regent University Virginia Beach, VA 23464-9800 Tel.: (804) 579-4215, Fax: (804) 579-4291 Running head: MARKETING AIDS PREVENTION (in press) Journal of Consumer Psychology A previous version of study #2 was presented to the Health Communication Division International Communication Association, Sydney, AUSTRALIA, July 14, 1994. Michael D. Basil (Ph.D., Stanford University) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Mass Communications at the University of Denver. His research interests focus on the processing and effects of health messages. William J. Brown (Ph.D., University of Southern California) is Professor and Dean of the College of Communication and the Arts at Regent University. His research interests focus on the international and intercultural dimensions of social influence. Many thanks to Renee Klingle, Debra Basil, Frank Kardes and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Marketing AIDS prevention 2 Abstract Social marketing may be used to change people's AIDS risk perceptions. Two competing hypotheses address those perceptions. First, the impersonal impact hypothesis proposes that mass communication affects judgments of societal risk while interpersonal communication affects judgments of personal risk. Second, the differential impact hypothesis proposes that the media affect personal risk judgments when the message involves a personalized depiction. Identification is proposed as the mechanism. These predictions were investigated in two studies of Magic Johnson's announcement that he was HIV positive. The first study compared the effects of naturally-occurring mass and interpersonal communication. The second study assigned students to watch tapes of the news story or to participate in interpersonal discussion. The results are generally inconsistent with the differential impact hypothesis. Because respondents' identification with Magic Johnson was a determinant and mediator of social and personal concern in both studies, the results support the importance of the identification process. Marketing AIDS prevention 3 Marketing AIDS prevention: The differential impact hypothesis versus identification effects Advocates of social marketing suggest that marketing theories and methods may be applied to improve the health of individuals (Andreason, 1995; Kotler & Zaltman, 1971; Manoff, 1985). Recently, interest has developed in how best to prevent the spread of AIDS in the population (Andreason, 1995; Braus, 1995; Golden & Johnson, 1991). Several studies in communication, marketing, psychology, and public health have examined increasing media coverage of the AIDS epidemic and AIDS-related knowledge (Basil & Brown, 1994; Brown & Basil, 1995; McAllister, 1991; Rogers, Dearing, & Chang, 1991). Less is understood, however, about the effects of exposure to this AIDS-related information or its subsequent impact on the audience's concern and behavior. The desired outcome of this exposure is that the hearer will come to perceive the risk as larger, and, as a result, take steps to prevent the disease. Although AIDS knowledge does not necessarily affect a person's sexual behavior (Baldwin, Whiteley, & Baldwin, 1990), risk perception has been shown to be an important behavioral predictor (Yep, 1993). One critical question is how to actually change risk perceptions and behavior. Although the mass media are generally effective at reaching a large number of people in a shorter time (Freimuth, 1992), evidence suggests that interpersonal channels are more effective in promoting precautionary sexual behaviors (Kashima, Gallois, & McCamish, 1992). The purpose of the present study is to analyze the effects of both mass and interpersonal communication in altering individuals' concern about AIDS. Specifically, we examined the effects of students' exposure to a news story of "Magic" Johnson's HIV infection, discussions of Magic Johnson's infection, and identification with Johnson on AIDS-related societal and personal concern. Marketing AIDS prevention 4 AIDS communication effects During the latter part of the 1980s, the United States government and news organizations distributed many educational messages through the media to increase knowledge of HIV and its transmission. In 1988 alone, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) supplemented that information with an estimated 18 million dollars worth of air time to broadcast AIDS educational messages ("A Misfire in the AIDS Fight," 1988). As a result of these campaigns, the public's awareness and knowledge of HIV and AIDS increased dramatically (Dearing & Rogers, 1992; Rogers, Dearing & Chang, 1991). By 1988, an estimated 95 percent of the U.S. adult population is aware of how AIDS and HIV are transmitted (Dawson, Cynamon, & Fitti, 1988). Much of this information was intended to increase individuals' concern about the disease. The intention was not to produce a panic, but to produce a rational, informed public that could react accordingly (Kasperson et al., 1988; Mazure, 1989). When provided with the proper alternatives, personal concern about AIDS was proposed to lead to avoidance of risky sexual behavior (Keeter & Bradford, 1988; Shiltz, 1987; Stall, Coates, & Hoff, 1988). Personal concern was also believed to reduce the occurrence of enacting high-risk sexual behavior (Coates et al., 1987). Research confirmed that media coverage of AIDS increased the public's concern about the disease (Edgar, Hammond, & Freimuth, 1989; Quinley, 1988; Singer, Rogers, & Corcoran, 1987; Worchester, 1988). Among heterosexuals attending college, knowledge of AIDS is fairly high (Carroll, 1988; Freimuth, Edgar, & Hammond, 1987; Goodwin & Roscoe, 1988; Katzman, Mulholland, & Sutherland, 1988; Stiff, McCormack, Zook, Stein, & Henry, 1990). This is important since the college-age group is at high risk for HIV infection (DiClemente, 1990; Leukfeld & Haverkos, 1993; Renshaw, 1989; NIH, 1993). Studies have shown that most students are aware of the means of transmission of HIV and the ways of contracting HIV infection. When risk perceptions are examined, however, research indicates that knowledge does not necessarily translate into perceptions of personal risk or, ultimately, behavior to reduce risk (Baldwin & Marketing AIDS prevention 5 Baldwin, 1988; Baldwin, et al., 1990, Becker & Joseph, 1988; Carroll, 1988; Edgar, Freimuth, & Hammond, 1988; Goodwin & Roscoe, 1988; Katzman et al., 1988; Kegeles, Adler, & Irwin, 1988; Maticka-Tyndale, 1991). Despite knowledge of safer sexual behaviors (Francis & Chin, 1987; Siegel, Grodsky, & Herman, 1986), college students have not adopted these practices. This population, therefore, continues to be at risk (Bush, Ortinau & Bush, 1994; DiClemente, 1990). Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses According to the Health Belief Model (Kirsch, 1988; Kirsch & Joseph, 1989), healthy behavior is determined by perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers. With AIDS, all these factors should be important predictors of sexual behavior. Because most people understand the nature of HIV and AIDS, severity and benefits are not likely to vary across individuals. Therefore, there are at least two explanations for the lack of a correspondence between knowledge and perceptions of risk. First, young adults do not feel susceptible (Chilman, 1983). Although they may intellectually understand the disease and the means of transmission (Dawson, Cynamon & Fitti, 1987; Gallup Poll, 1988), they have an unrealistic self-serving bias that minimizes their perceptions of AIDS as a personal threat (Hansen, Hahn, & Wolkenstein, 1990; Sisk, Hewitt & Metcalf, 1988). A second possible explanation why knowledge may not predict risk perception is the nature of the messages themselves. Specifically, theorists have speculated that although the mass media can convey risk, this is often portrayed as a risk for generalized others that the audience can dismiss as "not like me" (Snyder & Rouse, 1995). These explanations are the basis for the following discussion and experiment. They also provide the basis for two hypotheses seeking to explain communication and risk assessment. Marketing AIDS prevention 6 The Impersonal Impact Hypothesis In 1984, Tyler and Cook proposed the "impersonal impact hypothesis" to explain people's risk perceptions. This hypothesis proposed that people may assess personal and societal risks separately. Personal level risk assesses individual vulnerability -- "How likely am I to get the disease?" Societal risk examines a person's estimate of the generalized risk to the rest of the population -- "How likely are others around me to get the disease?" Tyler and Cook predict that the mass media influence societal-level risk evaluations to a greater extent than they affect personal-level judgments. Several studies have supported this prediction (Culbertson & Stempel, 1985; Doob & McDonald, 1979; Hughes, 1980; Pilisuk & Acredolo, 1985; Skogan & Maxfield, 1981; Tyler, 1980). This theory proposes that the mass media generally discuss health risks to society, while interpersonal interactions generally focus on stories of personal experiences with AIDS and HIV -- often focusing on friends. Therefore, interpersonal communication, which makes stories more personally salient, is believed to have a larger effect on concern about personal risk than mass media stories. Based on this theory, Hypothesis 1 proposes that: (a) Exposure to media depictions of Magic's infection will result in higher estimates of societal risk; while (b) exposure to interpersonal discussion will result in higher estimates of personal risk. Marketing AIDS prevention 7 The Differential Impact Hypothesis Some of the research aimed at examining the impersonal impact hypothesis, however, has not found evidence to support differences in the impact of mass media and interpersonal communication on personal and societal-level concerns (Coleman, 1993; Snyder & Rouse, 1995). Instead, it appears that the impersonal effects occur only under certain conditions. These conditions have been addressed most directly by the differential impact hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the personal relevance of a message determines its impact (Tyler & Cook, 1984). Snyder and Rouse (1995) have proposed that mass media depictions that are vivid or dramatic may also affect judgments of personal risk (Snyder & Rouse, 1995). Interpersonal communication appears more likely to convey personal stories. It may be this relevance and vividness which may actually be determining the effectiveness of the message on risk perceptions. When media messages are more personally involving, they may also be more effective in conveying personal risk. It has been shown that perceived realism of the depiction does determine the effect of media depictions (Reeves, 1978; Sussman et al., 1989). Identification One way to personalize the depiction is through providing a dramatic presentation or a real story about someone whom the person knows. A test of this approach confirmed that media depictions using dramatizations affected perceptions of personal risk of AIDS, although news media stories did not (Snyder & Rouse, 1995). To date, however, the exact mechanism of the differential impact or how this personalization occurs is not fully understood. The theories of dramatic effects suggest that a person's identification with the subject of a story or a perceived role model determines the message's effectiveness (Bandura, 1986; Burke, 1950; Kelman, 1961). Previous studies have shown that the effects of health stories are also contingent on whether a person feels a connection with the person or persons in the story (Basil, 1996; Brown & Basil, 1995). This finding suggests that personalization of the story should result in higher perceptions of personal concern and risk. After seeing a story, people are likely to feel concern depending on how much they identify with the character of the story. According to this approach, it is Marketing AIDS prevention 8 the combination of the message itself with people's perceptions of the similarity of the depicted character that determines the effectiveness. Typically, the impersonal impact hypothesis is investigated by comparing two or more messages that vary with regard to whether the issue has been personalized or not. The importance of personal relevance, however, is that the level of identification can also vary across people. Harkening back to theories of identification it is possible that in reacting to the same depiction, some people may feel that the person is similar to themselves, others may feel that the person is not. The attribution of how much people identify with the model can also determine the message's effectiveness, a situation Baron and Kenny (1986) predicted would result in a mediated variable. An extension of the differential impact hypothesis, then, predicts that the variation in the personalization depends on a person's identification with the character presented. As a result, this approach proposes that personalization not only varies across messages, but also across different hearers of the same message (Basil, 1996). This approach suggests that a person's identification with the person depicted in the message may determine whether an appeal is effective. Celebrity effects One of the most used strategies for invoking identification is to use a celebrity. It has been shown that exposure to media personalities over time, even though the exposure is via the media, leads people to develop a sense of intimacy and identification with that celebrity. This phenomenon was described by Horton and Wohl (1956) as a parasocial relationship. Parasocial relationships with media personalities commonly occur because media audiences think or feel as if they know the media personalities to which they are regularly exposed (Rubin & McHugh, 1987). Popular tabloids, magazines, television news-entertainment programs, and even the mainstream press offer information with which a person can follow his or her favorite celebrity. Celebrities, then, may have a special ability to instill this perceived intimacy (Fowles, 1992). Marketing AIDS prevention 9 The research which has examined the influence of celebrities has found they are effective in invoking identification. Adams-Price and Greene (1990) found that adolescents identify with celebrities. Greene and Adams-Price (1991) showed that people's beliefs in a celebrity's personality were biased as a result of the identification process. Alperstein (1991) found that people's relationships with television celebrities could be described as a pseudo-social interaction where viewers are "involved" in this relationship. In addition, McCracken (1989) proposed that the effectiveness of a celebrity is determined by the cultural meanings with which they are endowed. The greater the identification, the more likely the person will see important attributes in the celebrity. Williams and Qualls (1989), for example, found that Black consumers have high levels of identification with Black celebrities. Other research has shown that celebrities can have an effect on people's behavior. Kahmen, Azhari, and Kragh (1975) found that advertisements featuring Johnny Cash led to greater awareness of the ads and a more positive corporate image. Friedman, Termini, and Washington (1977) found that wine ads with Al Pacino were rated higher than those with a company president, a typical consumer, or no source. Friedman and Friedman (1979) found that ads using Mary Tyler Moore as a spokesperson led to higher ratings of the ad, attitude toward the product, and purchase intention for products involving image or taste, and led to better ad and brand name recall regardless of the product. Kahle and Homer (1985) found that razor ads featuring attractive celebrities resulted in better attitudes toward the ad than ads featuring less attractive celebrities. More generally, Graham (1991) found that celebrity charisma allows them to have "sheeplike, highly motivated followers (p. 105)." Hammond, Freimuth, and Morrison (1990) found that radio station program directors were significantly influenced in their choice of whether to air a public service announcement because of the presence of a celebrity spokesperson. Identification with celebrities is even believed to be so powerful that it drives suicide rates (Stack, 1987, 1990a, 1990b) and cocaine use (Kleber, 1988). Further research examined contingent conditions in the identification process. Atkin and Block (1983) found that only younger subjects rated celebrity-based alcohol advertisements more favorably Marketing AIDS prevention 10 than non-celebrity based advertisements; older subjects did not. Kahle and Homer (1985) found that the attractiveness of the celebrity was also an important condition underlying identification, attitudes toward the product, and purchase intentions. Buhr, Simpson, and Pryor (1987) and Ohanian (1991) have shown that a celebrity with expertise about the product was significantly more effective than a non-celebrity expert. Kamins (1990) and Misra (1990) described this effect as a "match" between the product and celebrity. These results generally indicate that a celebrity is more effective than a non-celebrity, especially when there is some level of expertise offered by the celebrity. Some research has focused directly on the effect of celebrities on AIDS prevention. The results suggest that the process of identification can be applied to AIDS messages. For example, Magic Johnson was found to be a good spokesperson for AIDS. Mays, Flora, Schooler, and Cochran (1992) found that Magic Johnson was perceived as credible among samples of both homeless people and college students. Kalishman and Hunter (1992) showed that Magic's announcement significantly increased individuals' concern about AIDS, interest in AIDS information, and communication with friends about AIDS. Basil and Brown (1994) showed that Magic Johnson's announcement was quickly diffused among a college community. Brown and Basil (1995) showed that identification played a large role in the effectiveness of Magic Johnson's advocacy of safe sex behavior. Basil (1996) showed that the identification effect mediated people's perception of their own risk and behavioral intentions a whole year after Magic's announcement. All of these studies support the critical importance of the source in persuasion. A good source is more likely to be effective in advocating a position or behavior (Bowen, & Michael-Johnson, 1990). In some instances speaker credibility may be the important factor. In other instances the major factor may be a speaker's attractiveness (Chaiken, 1980; Kahle & Homer, 1985). It has recently been suggested that the extent to which people identify with the source of the message may also determine how effective the message is (Basil, 1996). Specifically, identification can mediate the message's effectiveness. This extension of the differential impact hypothesis leads us to predict that a person's identification with a Marketing AIDS prevention 11 character is the mechanism that determines whether a dramatic depiction determines personal concern. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 proposes that: (a) The level of identification with the person associated with a health message will determine the degree of personal concern that person feels about that health risk, and (b) the level of identification will mediate the perception of personal risk. Finally, the literature is inconclusive as to whether the differential impact will only affect personal concern, or could also affect social concern. Perhaps through identification, personalized media depictions can also alter social level judgments. In order to investigate this question, we proposed the following Research Question: Will the level of identification with the person associated with a health message determine the degree of social concern about that health issue? To test these predictions and explore the research question, two studies were conducted. The first was a post-facto survey, the second was a quasi-experiment. Study 1 The first test of these hypotheses made use of a survey to examine the impact of naturally-occurring mass and interpersonal communication. In this way, it was most similar to previous studies of the impersonal impact and differential impact hypotheses (Coleman, 1993; Tyler & Cook, 1984; Snyder & Rouse, 1995). Method A survey was administered approximately one week after Johnson's announcement. A total of 67 questions were asked. The survey examined demographic information, interpersonal communication, media use, knowledge of Magic Johnson's HIV announcement, identification with Magic Johnson, risk perceptions, and intended sexual behavior. Marketing AIDS prevention 12 Subjects. One hundred and ninety-one students at a large Western University completed a survey for extra credit. Fifty-eight percent (225) were female, forty-two percent (163) were male, 3 did not report their gender. Their ages ranged from 17 to 50. The median age was 22. Measured variables. All items were asked on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale.1 The risk items were subjected to confirmatory factor analyses. Two factors were confirmed, social and personal risk. Based on this factor analysis, the reliabilities of these items were examined. Both scales yielded a minimum level of reliability after eliminating one item from each. 2 The resulting social risk scale yielded an alpha reliability coefficient of .62. The personal risk scale showed an alpha reliability of .62. Although the reliabilities were fairly low, they were comparable to previous scales measuring AIDS-related attitudes (Herek & Glunt, 1991). As such, they were deemed acceptable (Cohen & Cohen, 1983, p. 412). Identification with Magic Johnson was measured with 8 items. This was also subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis. Results confirmed a single identification factor. Two questions were reversed. Analysis revealed these items to be a reliable scale (Cronbach's alpha=.85). Media use was separated into print media use and television media use. Although significantly correlated (r = .56), the two media measures appeared as separate factors in a factor analysis (Cronbach's alpha = .62 and .63). Interpersonal communication was constructed from two questions asking about number of people that they had talked to about HIV and AIDS (Cronbach's alpha = .65). Results Social risk. The first regression analysis examined the determinants of social level concern. Results of this analysis are discussed below. First, the analysis controlled for the effect of the covariates on social risk concern. The respondent's age showed a marginally significant effect on social concern (Beta=-.094, p = .08). Gender showed a significant relationship with perceptions of social risk (Beta=.180, p < .001). Directionally, women showed more concern about AIDS than men. Culture showed no relationship (Beta=.004, p > Marketing AIDS prevention 13 .10). Previous sexual experience showed no significant relationship with social concern about AIDS (Beta=-.009, p > .10). Hypothesis 1a predicted people who are exposed to media depictions of Magic's infection would be more concerned about societal AIDS risk. The regression showed a positive relationship with print exposure (Beta=.148, p = .008). Television exposure also showed a positive relationship to social risk perception (Beta=.176, p = .005) in the predicted direction. There was no relationship between interpersonal discussion condition and social concern (Beta=.076, p > .10). The research questions asked about a possible relationship between identification with Magic Johnson and social concern. Only a marginally significant relationship was discovered (Beta=.104, p = .07). Directionally, identification was positively related to social risk perception. Personal risk. A second regression examined determinants of personal level risk. The results of this analysis are discussed below. First, the analysis controlled for the effect of the covariates on personal risk concern. Here, respondents' age showed no significant effect on personal concern (Beta=-.081, p > .10). Culture showed no significant relationship with person concern either (Beta=.087, p > .10). Gender, however, showed a significant relationship with perceptions of personal risk (Beta = .112, p = .03). Previous sexual experience also showed a significant relationship with personal concern about AIDS (Beta = .121, p = .02). The regression showed a significant effect of print exposure (Beta=.124, p = .01) on social risk. Television exposure was also significantly related to perception of personal AIDS risk (Beta=.141, p < .01). Hypothesis 1b predicted people who are exposed to interpersonal discussion of Magic's infection would be more concerned about personal AIDS risk. This relationship of interpersonal discussion condition with personal risk was initially observed (Beta=.113, p = .03), but disappeared when identification with Magic Johnson was included in the equation (Beta=.054, p > .10). In this case, mass media use was related to higher concern about personal risk. Marketing AIDS prevention 14 Hypothesis 2a predicted that identification with Magic Johnson would result in higher personal concern about AIDS. The expected relationship was found (Beta=.189, p < .001), consistent with Hypothesis 2a. Again, no interactions between these predictors were observed. Mediational tests. Additional tests were conducted to examine Hypothesis 2b, that the level of identification would determine personal perceptions. In accord with Baron and Kenny's rules (1976), a series of three regressions examined whether there were relationships between (a) the IV and mediator, (b) the IV and the DV, and (c) the mediator and DV. We also examined whether the introduction of the mediator reduced the contribution of the IV. The results of these regressions show the identification strongly mediated the relationship between interpersonal communication and personal risk (Betas = .37, .12, and .28, respectively, Beta dropped to .02 [n.s.] when identification was included). The same effect was also found for interpersonal communication and social risk (Betas = .37, .11, and .17, respectively; Beta for TV dropped to .04 [n.s] when identification was included). In addition, partial mediation effects of identification were observed between (a) TV and social risk, (b) print and social risk, (C) TV and personal risk, and (d) print and personal risk. These results are generally consistent with Hypothesis 2b. Discussion The results of this study were somewhat consistent with the Impersonal Impact Hypothesis. The relationship between mass communication and social risk predicted by Hypothesis 1a was observed. The relationship between interpersonal communication and perceptions of personal risk as predicted by Hypothesis 1b was also observed. However, when identification with Magic Johnson was included, the relationship between interpersonal communication and perceived personal risk disappeared. In addition, unpredicted positive relationships between print and television exposure were found with perceptions of personal risk, suggesting the mass media had affected perceptions of personal risk. These findings suggest that the communication effects, at least in this case, were not confined to the domains predicted by the Impersonal Impact Hypothesis, and appear to be contrary to its intent. Marketing AIDS prevention 15 The Differential Impact hypothesis, meanwhile, predicted that involving media depictions could affect both social and personal perceptions of risk. This effect was observed in this case. In order to examine whether the vividness or drama of the story determined its impact, Hypothesis 2a proposed that the level of identification with the person depicted would predict the effectiveness of media messages on personal concern. Here, consistent with the Differential Impact Hypothesis, identification with Magic Johnson was a significant predictor of personal risk perception. Identification was also a significant predictor of social concern. Further, consistent with Hypothesis 2b, identification mediated the relationship between mass communication and personal risk, at least partly. In addition, however, identification strongly mediated the relationship between interpersonal communication and both personal and social risk. Further, identification also partly mediated the relationship between mass communication and social risk. These two results suggest that the mass media did have an effect on both social and personal risk. In this case, however, not only did identification with Magic Johnson have a significant effect on both personal and social risk, but the effects of mass communication also appeared to play a direct role in risk assessment. These mass communication effects were partly mediated by identification. Interpersonal communication effects, meanwhile, were strongly mediated by identification. The net effect of mass and interpersonal communication, then, could best be described as rather "synergistic" with identification effects. This study is limited because, as with the previous studies of the differential impact hypothesis, interpersonal and mass communication were naturally occurring. There are two important limitations with this approach. First, as with all surveys, self-selection could bias the results. Subjects who are more interested in the AIDS issue may have watched or remembered more stories about the issue, and felt closer affiliation with Magic Johnson's plight. This could have biased the findings. A greater interest in the topic could drive risk perceptions first, and then media use and interpersonal communication. If this were occurring, then communication would essentially perform a function of Marketing AIDS prevention 16 "preaching to the converted," and have limited ability to affect those without existing concern. Second, the effect of specific news stories cannot be ascertained (Snyder & Rouse, 1995). That is, we have no way of knowing whether one specific story may have changed social or personal risk perceptions, instead of being an effect of the medium in which the story was transmitted. Study 2 Method Most of the earlier research in this area, including the previous study, has used survey research to examine the relationship between media viewing and interpersonal communication on risk perceptions. To avoid the limitations discussed above, the present study used assignment to conditions to compare the effects of assigned news viewing and a structured interpersonal discussion on participants' perceptions of AIDS risk. We believe this situation allows a test of the types of classroom-based interventions available to social marketers. While the earlier studies examined the effect of a series of messages, thus making it impossible to assess the effect of a single message, this study will focus on single messages. Although it is likely that the effects of a single message will be fairly small, it is hoped that the triangulation of these two strategies will provide additional insight into the effects of these interventions. Subjects. Three hundred sixty-one college students at a large university in the western United States served as subjects in the experiment. Fifty-eight percent (205) were female and forty-two percent (151) were male (five respondents did not give their gender). The age range was 17 to 41. The median age was 22.0. The two largest racial groups were Asian-Americans and European-Americans, respectively. Ninety-nine percent of subjects identified themselves as heterosexual. Marketing AIDS prevention 17 Design. This study used a modified Solomon 4-group experimental design. Four classes were in the post test-only control condition. Two classes were in the pre-and-post control condition. These two groups were subsequently combined to provide one "control" condition. Six classes saw the mass media news message and received both the pretest and post test. The final six classes participated in interpersonal discussions and received both the pretest and post test. These classes were "matched" as much as possible; for example, of the four "Public Speaking classes," one was assigned to each condition. The upper division electives were similarly distributed among conditions. Experimental procedure. Experimental interventions occurred during the week of November 25, 1991. This was approximately 11 days after Earvin "Magic" Johnson's news conference on his positive HIV status and initial retirement from professional basketball. Classes were assigned to one of two control, a mass media viewing, or an interpersonal discussion condition. In the mass media condition, subjects watched an in-class videotape of the mass media news story of Magic's announcement that he was infected with HIV and quitting professional basketball. Subjects in the interpersonal discussion condition participated in three-person in-class small-group discussions of the same news story. A short protocol was given to facilitate discussion. Even though most participants had not seen Johnson's news conference, it was not expected that this would be people's first exposure to this information. Instead the study sought to examine whether additional exposure to this information, through the mass media or as a subject of interpersonal discussion, could be used to influence risk perceptions. This procedure, therefore, was used to test whether further viewing of media information, or personal discussion about it, might be a fruitful means for changing people's risk perceptions, as might happen in a classroom setting or public health intervention. Marketing AIDS prevention 18 Posttest Questionnaire. The evaluation of participants' perceptions of AIDS risk occurred one week after the experimental manipulation. A 55-item questionnaire was distributed to 17 upper- and lower-division speech classes. All students completed the questionnaires. Eight questions collected demographic information including age, gender, and cultural orientation. Eleven items measured respondents' identification with Magic Johnson. Three questions addressed respondents' personal risk, and three asked about personal concern over societal risk to AIDS. Two other items asked about previous and future sexual behavior. Measured variables. The risk items were also subjected to confirmatory factor analyses. Again, two factors emerged. Both scales yielded a minimum level of reliability after eliminating one item from each. The resulting social risk scale yielded an alpha reliability coefficient of .62. The personal risk scale showed an alpha reliability of .63. Although the reliabilities were fairly low, they were comparable to the previous measure of AIDS-related attitudes. As such, they were deemed acceptable. Identification with Magic Johnson was measured with 8 items. This was also subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis and revealed a single factor. Two questions were reversed. Analysis revealed these items to be a reliable scale (Cronbach's alpha=.78). This scale, therefore, compared reasonably with its earlier use where the alpha reliability was reported as .85. Results No significant differences between the groups were found on any of the demographic variables -age, gender, culture, or number of previous sexual partners. This suggests that the assignment of classes to conditions was effective and that groups were equivalent. In terms of outcome measures, a significant difference across the three groups was observed for social risk perceptions (F[3,355]=3.54, p<.02); however, no significant differences were found for personal risk perceptions (F[2,356]=0.46, p>.10). The means for social and personal level risk between the three groups can be seen in Table 1. Means are based on a seven-point Likert scale, with 7 indicating the highest degree of concern. Marketing AIDS prevention 19 ______________________________________________ Insert Table 1 here _______________________________________________ This finding suggests that interpersonal communication had a significant effect on social risk perceptions. Contrary to Hypothesis 1a, however, interpersonal communication appears to have lowered social risk perception. Subsequent analyses examined the specific determinants of both social and personal concern level for individuals. The first regression analysis examined the determinants of social level concern. The mean level of social concern was 6.0. Results of this regression are discussed below. The first part of the analysis controlled for the effect of the covariates on social risk concern. Neither age nor culture had a statistically significant effect on social concern (p > .10). As in the previous study, women showed more concern than men (Beta=.110, p = .05). Previous sexual experience showed a significant relationship with social concern about AIDS (Beta=.140, p = .01). Hypothesis 1a predicted people who are exposed to media depictions of Magic's infection would be more concerned about societal AIDS risk. The regression showed no significant effect of exposure to the media message on concern about the social risk of AIDS (Beta=-.077, p > .10). There was, however, an unexpected negative relationship between being in the interpersonal discussion condition and social concern (Beta=-.308, p = .03). Instead of increasing concern, participation in the interpersonal discussion served to lower concern about others' risk.3 As in the first study, however, when identification with Magic Johnson was included, the interpersonal communication effect vanished (Beta=-.094, p > .10). The Research Question examined the relationship between identification and social concern about AIDS. The regression showed a significant relationship between identification and social concern (Beta=.195, p < .01). There was no significant interaction between identification and mass or interpersonal communication, as would be predicted if identification moderates the effect (p > .10). Marketing AIDS prevention 20 A second regression examined determinants of personal level risk. The mean level of personal risk was 4.8. This regression showed that respondents' age, gender, culture, and previous sexual experience were significant predictors of personal concern (p < .05). Age showed a negative correlation with personal concern (Beta=-.111, p =.05) such that older people were more concerned about their risk level. No gender differences were observed, however (Beta=.069, p > .10). Culture showed that Caucasians were marginally more concerned than non-Caucasians (Beta=.103, p = .06). Previous sexual activity showed a positive relationship with personal concern (Beta=.205, p <. 001). The higher the sexual activity, the higher the personal concern. These findings are generally in accord with subjects' actual risk. Hypothesis 1b predicted that people exposed to interpersonal discussion of Magic's infection would lead to more concern about personal risk. The regression shows a significant effect of interpersonal discussion on personal concern in the opposite direction (Beta=-.298, p = .03), which also disappeared when identification was included (Beta=-.120, p > .10). These results are counter to the impersonal impact hypothesis. No media exposure effect was observed (Beta=-.121, p > .10). Hypothesis 2a predicted a positive relationship between identification with a character and personal concern about AIDS. The second regression shows the predicted relationship between identification and personal concern (Beta=.163, p = .02). A higher level of identification with Magic was associated with a higher perception of personal risk. These results support the importance of identification. 4,5 Again, however, there was no significant interaction between identification and mass or interpersonal communication, as would be predicted if identification moderates the effect of the message (p > .10). Mediational analyses. Additional tests were conducted to examine Hypothesis 2b, that the level of identification would determine personal perceptions. In accord with Baron and Kenny's approach (1976), a series of three regressions examined whether there were relationships between (a) the IV and mediator, (b) the IV and the DV, and (c) the mediator and DV. We also examined whether the introduction of the mediator reduced the contribution of the IV. The results of these regressions show Marketing AIDS prevention 21 that identification strongly mediated the relationship between interpersonal communication and personal risk (Betas = -.11, -.35, and .17, respectively, Beta dropped to -.15 [n.s.] when identification was included). The same effect was also found for interpersonal communication and social risk (Betas = -.11, -.31, and .16, respectively, Beta for media dropped to -.12 [n.s] when identification was included). No mediation effects of identification were observed between media and social risk or media and personal risk. These results are somewhat consistent with Hypothesis 2b, but only with regard to mediating the effects of interpersonal communication. Discussion This second study examined social and personal concern about AIDS. With regard to predictors of social concern, the study attempted to examine the effect of a single specific mass or interpersonal message. There was no observable effect of viewing a single media message. Interpersonal discussion, however, did appear to have an effect on people's perception of others' risk; unfortunately, however, in this study it lowered perception of others' risk. Identification with Magic Johnson not only increased the perception of social risk, but also mediated the effect of interpersonal communication on social risk perception. When people identified with Magic, they were less susceptible to the argument that they had little to worry about. With regard to personal concern, older and more sexually active participants showed greater personal concern about AIDS. This is generally consistent with actual risk factors. This suggests that college students apply the correct factors in assessing their personal risk level. These findings further suggest that people not only make separate personal and social risk judgments, but are also able to apply appropriate realistic risk factors to each judgment. Although viewing a media story did not appear to change a person's personal risk assessment, participating in interpersonal discussion did lower people's perceptions of their own risk. Identification with Magic Johnson did, however, show a significant relationship with personal risk perceptions. Again, identification with Magic Johnson was related to higher perceptions of personal risk. In addition, while people who did not identify with Magic Johnson Marketing AIDS prevention 22 had a reduced sense of personal risk as a result of the interpersonal discussion, this did not occur for those who identified with Magic Johnson. Importantly this intervention showed that interpersonal discussion can lower the perceived social risk for AIDS. With hindsight, this finding is somewhat consistent with studies that show people often engage in interpersonal discussion without increasing their use of condoms (Baldwin et al., 1990; Metts & Fitzpatrick, 1992). In those studies, interpersonal discussion did not necessarily result in the appropriate behaviors; in this study interpersonal discussion actually lowered risk perceptions. Much of the interpersonal discussion may have been directed toward minimizing risk perceptions through discussing the differences between discussants and Magic Johnson. Magic claimed, for example, to have had contact with many more women than the college students involved in the discussion. Other research has begun to examine the effectiveness of interpersonal communication in conveying personal risk (Cline, Johnson & Freeman, 1992). These studies show evidence that talk between potential partners often appears to focus on a "nominal assurance of safety" (Cline et al., 1992, p. 48). In this study it is likely that group participants participated in a "fear control" as opposed to "danger control" discussion (Witte, 1992a). Therefore, it appears that participating in discussions of AIDS will not necessarily increase or decrease concern. Instead, the resultant concern will depend on the nature of the discussion. If the desire is to increase perceptions of risk, perhaps it is necessary to make use of a facilitator to guide discussion. This guidance may take the form of providing participants with concrete actions and efficacy about their ability to perform those actions (Witte, 1992b). Despite the suggestion that participants discuss AIDS prevention in the discussion protocol, participants may not have had any good suggestions or may not have even discussed this point. It is interesting to note, however, that the interpersonal discussion did not lower participants' own perception of risk, just that for others. In accord with previous research, people were more concerned about risks to others than to themselves (Hansen, Hahn, & Wolkenstein, 1990; Quinley, 1988; Singer et al., 1987; Snyder & Rouse, 1995). Applied to models of behavior, this results in a greater likelihood of high-risk sexual behavior. Marketing AIDS prevention 23 Conclusion These two studies suggest that college students are active assessors of their own health risk. Providing them with appeals that say "you are at risk" are not automatically effective. Instead, college students appear to assess the validity of that claim. Personal concern depends on gender, age, and previous sexual activity. These are all important factors in their actual risk. These studies demonstrate that the mass media may have a significant effect in determining people's risk perceptions. We could not demonstrate, however, that the relationship is causal. A single media message had no measurable effects on personal or societal concern. This result is consistent with Snyder and Rouse (1995) where news coverage did not affect personal or social risk. Participating in interpersonal discussion does appear to be change participants' risk perceptions, even a single intervention. The first study interpersonal discussion found a significant relationship with both social and personal risk judgments. The second study showed that a single discussion was shown to be powerful enough to lower participants' perceptions of others' risk. For the purposes of social marketing interventions, then, it is important to prevent the discussion from taking the form of "fear control," a common function of group affiliation (Schacter, 1959; Witte, 1992a, 1992b). Consistent with our proposed mechanism for the differential impact hypothesis, identification with Magic Johnson affected both social and personal concern about AIDS. In both studies this effect was observed on both social and personal risk perceptions. It appears, then, that celebrities may be effective in conveying risk (Bandura, 1986; Burke, 1950; Kelman, 1961). The fact that the identification process determines this risk has important implications for future health campaigns. Other research on this topic can be found in Pryor and Reeder (1993). This importance of identification that was found in these studies is consistent with one reported by Brown and Basil (1995) and replicated by Basil (1996) where identification mediated people's personal concern, perception of personal risk, and intended changes in sexual behavior. Here, identification with Magic Johnson affected social and personal concern. People thought, "Magic is like me, so if it can Marketing AIDS prevention 24 happen to him, it can happen to me, too." The extent to which viewers identify with the source of a health message, including a celebrity, appears to determine whether they change the assessment of their own health risk. The results suggest that ability to personalize the risk appears not to be an attribute of a particular medium, but also an outcome of viewers' perception of themselves as similar to the person in the depiction or story. When the viewer identifies with the person in the story, the risk is personalized; when the person does not identify with that person, the personalization does not take place. If identification is the key, this might explain why studies of Magic Johnson's announcement find varying reactions (Graham, Weiner, Giuliano, & Williams, 1993; Penner & Frietze, 1993; Sigelman, Miller, & Derenowski, 1993; Whalen, Henker, O'Neil, & Hollingshead, 1994; Zimet, Lazebnik, DiClemente, Anglin, William & Ellick, 1993). Among any population, identification varies. The extent of the identification determines the effectiveness of that celebrity. Overall, the practical implications of this study are in accord with those offered by Snyder and Rouse (1995) -- media messages are more likely to affect concern when the message provides some form of personalization between the audience member and the conveyor of that information. While further research investigates the dynamics of the process, campaign planners should make more use of theories of modeling, identification, and self-efficacy to gain maximum benefit from campaigns targeted at changing risk perceptions and behavior, both mediated and interpersonal campaigns. Marketing AIDS prevention 25 Notes 1. The complete questionnaires are available from the first author. 2. One decision rule for using measurement scales is that the reliability coefficients (Cronbach coefficient alpha) must exceed 0.60 to be considered a reasonable construct for research purposes (Cohen & Cohen, 1983, p. 412). Given the large sample sizes here, the .60 level seemed unlikely to result in a Type I error. 3. Alternative orderings of entry into the regression analyses were also used. Results were entirely consistent with those obtained from first controlling for the effects of covariates. 4. Here, mass media and interpersonal discussion were dichotomous (0,1) "dummy" variables which reflected the experimental condition. Another analysis used a MANOVA to control for family-wise error rates. In this analysis, age, gender, and previous sexual experience served as covariates. Experimental condition served as the main effect. Results were entirely consistent with the regression results. 5. Not all of the students in the assessment of effects were present for the treatment -- the video presentation or interpersonal discussion. When the self-report of having seen the video of Magic Johnson's announcement was used as the independent variable the results are again consistent with those reported here -- mass media viewing had no effect while interpersonal discussion served to lower risk. This measure should be more robust to absences and provide a more appropriate individual-level measure of condition. Marketing AIDS prevention 26 References A misfire in the AIDS fight. (1988, October 24). Advertising Age, p. 16. Adams-Price, C., & Greene, A. O. (1990). Secondary attachments and adolescent self concept. Sex Roles, 22, 187-198. Alperstein, N. M. (1991). Imaginary social relationships with celebrities appearing in television commercials. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 35, 43-58. Andreason, A. R., (1995). Marketing social change: Changing behavior to promote health, social development, and the environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Atkin, C., & Block, M. (1983). Effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Journal of Advertising Research, 23, 57-61. Baldwin, J. D., & Baldwin, J. I. (1988). Factors affecting AIDS-related sexual risk-taking behavior among college students. The Journal of Sex Research, 25, 181-196. Baldwin, J. I., Whiteley, S., & Baldwin, J. D. (1990). Changing AIDS-and- fertility-related behavior: The effectiveness of sexual education. The Journal of Sex Research, 27, 246-262. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. Basil, M. D. (1996). Identification as a mediator of celebrity effects. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 40, 478-495. Basil, M. D., & Brown, W. J. (1994). Interpersonal communication in news diffusion: A study of "Magic" Johnson's announcement. Journalism Quarterly, 71, 305-320. Basil, M. D., Schooler, C., Altman, D. G., Slater, M., Albright, C. L., & Maccoby, N. (1991). How cigarettes are advertised in magazines: Special messages for special markets. Health Communication, 3, 75-91. Becker, M. H., & Joseph, J. G. (1988). AIDS behavioral change to reduce risk: A review. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 394-410. Braus, P. (1995). Selling good behavior. American Demographics, 17(11), 60-64. Brown, W. J. (1991). An AIDS prevention campaign: Effects on attitudes, beliefs, and communication behavior. American Behavioral Scientist, 34, 666-678. Marketing AIDS prevention 27 Brown, W. J. (1992). Culture and AIDS education: Reaching high-risk heterosexuals in Asian-American communities. Journal of Applied Communication, 20, 275-291. Brown, W. J. & Basil, M. D. (1995). Media celebrities and public health: Responses to "Magic" Johnson's HIV disclosure and its impact on AIDS risk and high-risk behaviors. Health Communication, 7, 345-370. Buhr, T. A., Simpson, T. L., & Pryor, B. (1987). Celebrity endorsers' expertise and perceptions of attractiveness, likability, and familiarity. Psychological Reports, 60, 1307-1309. Burke, K. (1950). A rhetoric of motives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Bush, R. P.; Ortinau, D. J., & Bush, A. J. (1994). Personal value structures and AIDS prevention. Journal of Health Care Marketing. 14, 12-20. Carroll, L. (1988). Concern with AIDS and the sexual behavior of college students. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 405-411. Centers for Disease Control. (1988, August). AIDS knowledge and attitudes. (DHHS Publication No. PHS 89-1250). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 752-766. Chilman, C. S. (1983). Adolescent sexuality in a changing American society: Psychological perspectives for the human services profession. New York: Wiley Interscience. Cline, R. J. W., Freeman, K. E., & Johnson, S. J. (1990). Talk among sexual partners about AIDS: Factors differentiating those who talk from those who do not. Communication Research, 17, 792-808. Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd. ed.). Hillsdale: N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Coleman, C.-L. (1993). The influence of mass media and interpersonal channels on societal and personal risk judgments. Communication Research, 20, 611-628.. Culbertson, H. M. & Stempel, G. H. (1985). Media malaise: Explaining personal optimism and societal pessimism about health care. Journal of Communication, 35, 180-190. Dawson, D. A., Cynamon, M., & Fitti, J. E. (1988). AIDS knowledge and attitudes for September 1987: Provisional data from the National Health Interview Survey. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics (PHS 88-1250, No. 146). Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service. Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. M. (1992). AIDS and the media agenda. In T. Edgar, M. A. Fitzpatrick & V. S. Freimuth (Eds.) AIDS: A communication perspective (pp 173-194). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Marketing AIDS prevention 28 DiClemente, R. J. (1990). The emergence of adolescents as a risk group for human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Adolescent Research, 5, 7-17. Doob, A. N., & McDonald, G. E. (1979). Television viewing and fear of victimization: Is the relationship causal? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 170-179. Edgar, T., Freimuth, V. S., & Hammond, S. L. (1988). Communicating the AIDS risk to college students: The problem of motivating change. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 3, 59-65. Edgar, T., Hammond, S. L., & Freimuth, V. S. (1989). The role of the mass media and interpersonal communication in promoting AIDS-related behavioral change. AIDS and Public Policy Journal, 4, 3-9. Fowles, J. (1992). Star struck: Celebrity performers and the American public. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Francis, D. P., & Chin, J. (1987). The prevention of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States. Journal of American Medical Association, 257, 1357-1366. Freimuth, V. S. (1992). Theoretical foundations of AIDS media campaigns. In T. Edgar, M. A. Fitzpatrick, &. V. S. Freimuth (Eds.), AIDS: A Communication Perspective (pp. 91-110). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Freimuth, V. S., Edgar, T., & Hammond, S. L. (1987). College students' awareness and interpretation of the AIDS risk. Science, Technology, and Human Values, 12, 37-40. Friedman, H., & Friedman, L. (1979). Endorser effectiveness by product type. Journal of Advertising Research, 19, 63-71. Gallup Poll (1988). AIDS: America's most important health problem. The Gallup Report (Report numbers 268-269). Princeton, NJ. Golden, L. L., & Johnson, K. A. (1991). Information Acquisition and Behavioral Change: A Social Marketing Application. Health Marketing Quarterly, 8, 23-60. Graham, S., Weiner, B., Giuliano, T., & Williams, E. (1993). An attributional analysis of reactions to Magic Johnson. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 996-1010. Goodwin, M. P., & Roscoe, B. (1988). AIDS: Students' knowledge and attitudes at a midwestern university. Journal of American College Health, 36, 214-222. Hammond, S. L., Freimuth, V. S., & Morrison, W. (1990). Radio and teens: Convincing gatekeepers to air health messages. Health Communication, 2, 59-67. Hansen, W. B., Hahn, G. L., & Wolkenstein, B. H. (1990). Perceived personal immunity: Beliefs about susceptibility to AIDS. Journal of Sex Research, 27, 622-628. Marketing AIDS prevention 29 Herek, G. M., & Glunt, E. K. (1991). AIDS-related attitudes in the U.S.: A preliminary study. Journal of Sex Research, 28, 886-891. Horton, D. & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19, 215- 229. Hughes, M. (1980). The fruits of cultivation analysis: A reexamination of some effects of television viewing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 44, 287-302. Kahle, L. R., & Homer, P. M. (1985). Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 11, 954-961. Kahmen, J., Azhari, A., & Kragh, J. (1975). What a spokesman does for a sponsor. Journal of Advertising Research, 16, 17-24. Kalichman, S. C., & Hunter, T. L. (1992). The disclosure of celebrity HIV infection: Its effect on public attitudes. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 1374-1376. Kamins, M. A. (1990). An investigation into the "matchup" hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. Journal of Advertising, 19, 4-13. Kamins, M. A., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., & Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: The impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of Advertising, 18, 4-10. Kashima, Y., Gallois, C., & McCamish (1992). Predicting the use of condoms: Past behavior, norms, and the sexual partner. In T. Edgar, M. A. Fitzpatrick, &. V. S. Freimuth (Eds.), AIDS: A Communication Perspective (pp. 21-46). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Gobel, J., Kasperson, J. X., & Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8, 177-187. Katzman, E. M., Mulholland, M., & Sutherland, E. M. (1988). College students and AIDS: A preliminary survey of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of American College Health, 37(3), 127-130. Keeter, S., & Bradford, J. B. (1988). Knowledge of AIDS and related behavior change among unmarried adults in a low-prevalence city. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4, 146-152. Kegeles, S. M., Adler, N. E., & Irwin, C. E. (1988). Sexually active adolescents and condoms: Changes over one year in knowledge, attitudes, and use. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 460-461. Kelman, H. C. (1961). Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25, 57-78. Kirsch, J. P. (1988). The health belief model and prediction of health actions. In D. S. Gochman (Ed.), Health Behavior: Emerging research perspectives (pp. 27-41). New York: Plenum. Marketing AIDS prevention 30 Kirsch, J. P. & Joseph, J. G. (1989). The health belief model: Some implications for behavior change, with reference to homosexual males. In V. M. Mays, G. W. Albae, & S. F. Schneider (Eds.) Primary prevention of AIDS: Psychological approaches (pp. 111-127). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Kleber, H. D., (1988). Epidemic cocaine use: America's present, Britain's future? British Journal of Addiction, 83, 1359-1371. Kotler, P. & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social marketing: An approach to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35, 3-12. Manoff, R. K. (1985). Social marketing: New imperatives for public health. New York: Prager. Maticka-Tyndale, E. (1991). Sexual scripts and AIDS prevention: Variations in adherence to safer-sex guidelines by heterosexual adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research, 28, 45-66. Mazure, A. (1989). Communicating risk in the mass media. In D. L. Peck (Ed.), Psychosocial Effects of Hazardous Toxic Waste Disposal on Communities (pp. 119-137). Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas. Mays, V. M., Flora, J. A., Schooler, C., & Cochran, S. D. (1992). Magic Johnson's credibility among African-American men. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 1692-1693. McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 310-321. Metts, S. & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (1992). Thinking about safer sex: The risky business of "know your partner" advice. In T. Edgar, M. A. Fitzpatrick, & V. S. Freimuth (Eds.), AIDS: A communication perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Misra, S. (1990). Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence: An assessment of recall and affect. Journal of Business Research, 21, 159-173. Ohanian, R. (1991). The impact of celebrity spokespersons' perceived image on consumers' intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, 31, 46-54. Penner, L. A., & Fritzsche, B. A. (1993). Magic Johnson and reactions to people with AIDS: A natural experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 1035-1050. Pilisuk, M. & Acredolo, C. (1988). Fear of technological hazards: One concern or many? Social Behavior, 3, 17-24. Pryor, J. B., & Reeder, G. D. (1993). The social psychology of HIV infection. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Quinley, H. (1988). The new facts of life: Heterosexuals and AIDS. Public Opinion, 11, 53-55. Marketing AIDS prevention 31 Reardon, K. K. (1988). The role of persuasion in health promotion and disease prevention: Review and commentary. In J. A. Anderson (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 11 (pp. 277-297). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Reeves, B. (1978). Perceived TV reality as a predictor of children's social behavior. Journalism Quarterly, 55, 682-689, 695. Renshaw, D. C. (1989). Sex and the 1980s college student. Journal of American College Health, 37, 154-157. Rogers, E. M., Dearing, J. W., & Chang, S. (1991). AIDS in the 1980s: The agenda-setting process for a public issue. Journalism Monographs, 126, 1-47. Schacter, S. (1959). The psychology of affiliation: Experimental studies of the sources of gregariousness. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Schooler, C., Basil, M. D., & Altman, D. G. (1996). Alcohol and cigarette advertising on billboards: Targeting with social cues. Health Communication, 8, 109-129. Siegel, K., Grodsky, P. B., & Herman, A. (1986). AIDS risk-reduction guidelines: A review and analysis. Journal of Community Health, 11, 233-243. Sigelman, C. K., Miller, A. B., & Derenowski, E. B. (1993). Do you believe in magic? The impact of "Magic" Johnson on adolescents' AIDS knowledge and attitudes. AIDS Education and Prevention, 5, 153-161. Singer, E., Rogers, T. F., & Corcoran, M. (1987). The polls - A report: AIDS. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51, 580-595. Sisk, J. E. Hewitt, M. & Metcalf, K. L. (1988). How effective is AIDS education? Health Affairs, 7, 37-51. Skogan, W. G. & Maxfield, M. G. (1981). Coping with crime: Individual and neighborhood reactions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Snyder, L. B. & Rouse, D. J. (1995). The media can have more than an impersonal impact: The case of AIDS risk perceptions and behavior. Health Communication, 7, 125-145. Stack, S. (1987). Celebrities and suicide: A taxonomy and analysis, 1948-1983. American Sociological Review, 52, 401-412. Stack, S. (1990a). A reanalysis of the impact on non-celebrity suicides: A research note. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 25, 269-273. Stack, S. (1990b). Audience receptiveness, the media, and aged suicide, 1968-1980. Journal of Aging Studies, 4, 195-209. Marketing AIDS prevention 32 Stall, R., Coates, T., & Hoff, C. (1988). Behavioral risk reduction for HIV infection among gay and bisexual men: A review of results from the United States. American Psychologist, 43(11), 878-885. Stiff, J., McCormack, M., Zook, E., Stein, T., & Henry, R. (1990). Learning about AIDS and HIV transmission in college-age students. Communication Research, 17, 743-758. Sussman, S., Dent, C. W., Flay, B. R., Burton, D., Craig, S., Mestel-Rauch, J., & Holden, S. (1989). Media manipulation of adolescents' personal level judgments regarding consequences of smokeless tobacco us. Journal of Drug Education, 19, 34-57. Tyler, T. R. (1980). Impact of directly and indirectly experienced events: The origin of crime-related judgments and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 13-28. Tyler, T. R. & Cook, F. L. (1984). The mass media and judgments of risk: Distinguishing impact on personal and societal level judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 693-708. Whalen, C. K., Henker, B., O'Neil, R. Hollingshead, J. (1994). Preadolescents' perceptions of AIDS before and after Magic Johnson's announcement. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 19, 3-17. Williams, J. D., & Qualls, W. J. (1989). Middle-class black consumers and the intensity of ethnic identification. Special Issue: Psychology, marketing, and the Black community. Psychology and Marketing, 6, 263-286. Witte, K. (1992a). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 328-349. Witte, K. (1992b). The role of threat and efficacy in AIDS prevention. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 12, 225-249. Yep, G. A. (1993). Health beliefs and HIV prevention: Do they predict monogamy and condom use? Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 8, 507-520. Zimet, G. D., Lazebnik, R., DiClemente, R. J., Anglin, T. M. (1993). The relationship of Magic Johnson's announcement of HIV infection to the AIDS attitudes of junior high school students. Journal of Sex Research, 30, 129-134. Marketing AIDS prevention 33 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------TABLE 1: Social and personal concern by experimental condition -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------SOCIAL PERSONAL n -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Post-only control Pre-post control Mass media group 6.10 6.20 4.99 4.86 (42) (79) 6.30 4.85 (102) Interpersonal discussion 5.80 4.73 (138) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------