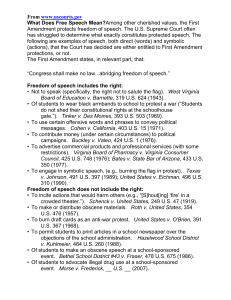

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus Inc.

advertisement