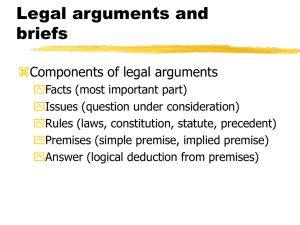

I. Arguments: argument 2. Arguments are made up of statements.

advertisement

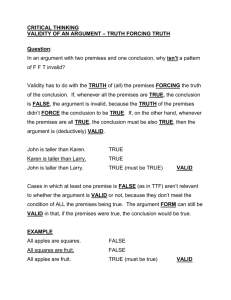

I. Arguments: 1. An argument, for the purposes of logic, is a bit of reasoning. 2. Arguments are made up of statements. 3. One is the conclusion—the statement the argument aims to support or justify. 4. Some are premises—these are not argued for, but used to support other statements. 5. We will understand what a good argument is when we know what it takes for an argument to succeed. Broadly, a good argument provides real support for its conclusion, while a bad one fails to support its conclusion. 6. ‘Support’ here requires reasons showing that its conclusion is true, or at least that it is likely to be true. 7. The first requirement is that a good argument must have true premises (false premises don’t give anyone good reason to accept anything) 8. Second, the conclusion must follow from those premises. That is, the truth of the premises must count in favour of (ideally, the truth of the premises should guarantee) the truth of the conclusion. 9. Finally, and somewhat more subtly, having evidence for each premise must not depend on assuming the conclusion- that is, grounds for believing each premise must be independent of believing the conclusion. 10. Further, it's impossible for an argument to do its job, i.e.: to give someone in particular good reasons to believe the conclusion is true, unless the premises themselves are believable or plausible for that someone. 11. And the argument can't do its job for someone in particular unless she can see that the premises do support the conclusion. 12. And even if there could be evidence for each premise independent of the conclusion, if the reasons someone has for accepting the premises do depend on the conclusion, the argument can't support the conclusion for that someone. 13. Each of these three requirements is an audience-centered partner of the corresponding requirement for correct persuasion, giving us the following table of features for a good argument: Requirements for Correct Persuasion: Audience-Centered Partner: True Premises. Plausible Premises. Premises do support conclusion. Audience sees that they do. Evidence for each premise is in The audience's evidence for principle independent of each premise is independent of assuming the conclusion assuming the conclusion. Any argument that has all these features is a pretty good one. It should persuade its audience, and if it does, the audience has been correctly persuaded- no mistake has been made. II. Anselm’s Ontological Argument: 1. God is “something than which nothing greater can be thought”. 2. Suppose for reductio: That than which nothing greater can be thought does not exist. 3. But something that does not exist cannot be such that nothing greater than it can be thought. (In particular, we can see that it would be greater if it actually existed: A perfect God who does not exist is not really that grand a thing at all!) 4. So, if it doesn’t exist, that than which nothing greater can be thought is something than which something greater can be thought. 5. But this is a contradiction. 6. So the supposition, That than which nothing greater can be thought does not exist. is, in fact, absurd: it leads directly to a contradiction. 7. Therefore, that than which nothing greater can be thought must exist, as a matter of definition! III. Guanilo’s Island: 1. Guanilo’s island is an island superior to all other lands, in terms of climate, resources, etc. 2. Suppose for reductio: This island does not exist. 3. But something that does not exist cannot be superior to all other lands. (In particular, we can see that any land with any resources at all would be superior to it: An island that does not exist is not superior to Canada, or England, or Malaysia!) 4. So, if it doesn’t exist, this wonderful island superior to all other lands is in fact inferior to many, if not all lands. 5. But this is a contradiction. 6. So the supposition, This island does not exist is, in fact, absurd: it leads directly to a contradiction. 7. Therefore, Guanilo’s island must exist, as a matter of definition!