Frankfurt: A metaphysical approach to compatibilism.

advertisement

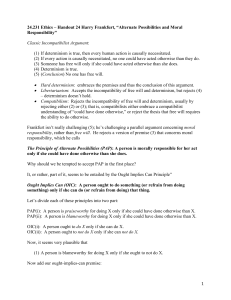

Frankfurt: A metaphysical approach to compatibilism. 1. The principle of alternative possibilities: (A) person is morally responsible for what he has done only if he could have done otherwise. (443) d’Holbach and Chisholm agree with this, and give it a categorical reading; Ayer agrees, but gives it a hypothetical reading. But Frankfurt claims that this principle is just wrong! 2. Coercion, hypnosis, inner compulsion: These are all construed as circumstances making it ‘impossible for the person to do otherwise’ (443). And Frankfurt agrees (in section II) that they render the action unfree, and the person not morally responsible. But Frankfurt rejects the view that this is because they leave the person with no alternative: The fact that a person was coerced to act as he did may entail both that he could not have done otherwise and that he bears no moral responsibility for his action. But his lack of moral responsibility is not entailed by his having been unable to do otherwise. 3. Frankfurt claims that a person can be in circumstances where it is guaranteed that the person will do it, without those circumstances moving or leading her to do it. 4. The key question, Frankfurt claims, is not whether someone could do otherwise, but ‘the roles we think were played, in leading him to act, by (his own) decision and by (any separate, compelling factor)’. (444) 5. So we come to the case of Jones, who decides to do something, then receives a threat demanding that he do it, and in fact does go on to do it. Frankfurt argues that our intuitions about whether Jones is responsible for the action turn, not on whether or not the threat left him with no alternative, but on what actually caused Jones to act as he did. Consider Frankfurt’s 3 Jones: Jones1, Jones2, and Jones3. 6. The key case is Jones3. Here we have someone who makes a decision, but whose range of alternatives is subsequently cut off because he receives a threat that would compel him to act as he has already decided, whatever he had already decided. But in fact the threat made no difference to him: He had already made his decision, and he acted on the grounds he had already considered. Here Frankfurt argues that (if we were truly confident that this was the situation) Jones3’s moral responsibility for the action would not be diminished, ‘For the threat did not in fact influence his performance of the action’. (445) 7. Here Frankfurt claims both (i) (ii) Jones3 was not coerced (since the threat actually had no effect). Jones3 had no alternative (since, if he hadn’t already decided to do what the threat demanded of him, the threat would have compelled him to do it anyway). 8. Even if we say Jones3 was coerced, though, Frankfurt maintains we would still regard Jones as morally responsible. So wherever we come down on the question of coercion, we should conclude here that the principle of alternative possibilities is wrong: moral responsibility does not require that we be able not to do the thing we are responsible for doing. 9. Frankfurt turns next to an objection: If, in fact, Jones3 was not really ‘moved’ to do as he did by the threat, then even though (in fact) we know that Jones3 would have been compelled by the threat if he hadn’t already decided to do as it demanded, we might simply deny that this implies that Jones3 could not have done otherwise. We might say, instead, that Jones3 could (in some sense) have defied the threat, had he so chosen. We might even (Frankfurt doesn’t remark on this) say that, since the threat did not affect his decision making process in the circumstances, we know that, in the relevant sense, he could indeed have defied the threat (unlike poor Jones2). 10. But Frankfurt’s next move is a clever slip past this objection. He introduces Black, who ensures that Jones4 will do as he wishes by observing very carefully as Jones4 is deciding what to do, and intervening only if he sees that Jones4 is about to do something else. (This requires only that there be some sign Black can detect that shows Jones4 is about to decide in the ‘wrong’ way, and that Black be able to intervene & alter this decision.) 11. Frankfurt now declares: ‘(S)uppose that Black never has to show his hand because Jones4, for reasons of his own, decides to perform and does perform the very action Black wants him to perform. In that case, it seems clear, Jones4 will bear …the same moral responsibility …as he would have borne if Black had not (been there at all).’ 12. What is up to Jones4 is not whether he does what Black wishes him to—it is only whether he does this of his own accord, or under Black’s influence. But if it’s the former, surely Jones4 is fully responsible for what he has done, despite his not having any alternative. 13. For Frankfurt, the key to moral responsibility is not whether we have alternatives, but what actually explains our actions. In the Jones3 and Jones4 examples, the action would have been the same even if the circumstances were changed to restore the availability of alternatives. If these alternative-eliminating circumstances actually played no role in producing the action, then Frankfurt says that responsibility is unaffected by their presence. 14. So, you might think, we get a new principle. A person is not responsible for some action if they did it because they had no alternative. But if they would have done the same thing anyway, the fact (if it is a fact) that they had no alternative is irrelevant. But this seems to imply that incompatibilism is true: In a deterministic world, there are always causes that operate to determine the agent’s action. So Frankfurt rejects this principle, in favour of a narrower view of the role of alternatives in responsibility: ‘A person is not morally responsible for what he has done if he did it only because he could not have done otherwise.’ (448) This position aims to capture the notion that there is a difference between doing something because it is what you wanted (all things considered, in the circumstances) to do, and doing it only because (in the circumstances) you were compelled to act against your preferences. One remark: I have no clear idea of what it means to do something only because one is compelled. This is a distinction that does not play any clear role in a deterministic picture of the world, though Frankfurt clearly supposes it’s compatible with a deterministic picture of the world. What could we mean by this? Is it something to do with a complex psychological distinction between “normally motivated” behaviour and behaviour that arises from some other sort of process (really compelled, in one of the ways Frankfurt considers at the outset)? Can a metaphysical take on this distinction really be arrived at (consider a very clever version of Black who keeps the ‘causal track’ of the decision within the parameters of normal motivation by subtle manipulations along that track!).