ENHANCING VETERAN ACADEMIC SUCCESS:

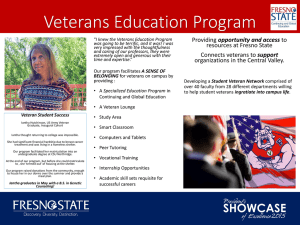

advertisement