DECOLONIZING EDUCATION: UNDERSTANDING HOW CLASSROOM

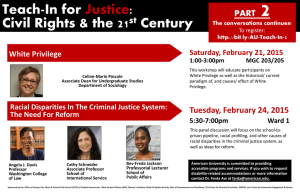

advertisement