COP 20 Briefing Paper: The Crucial Role of Smallholder

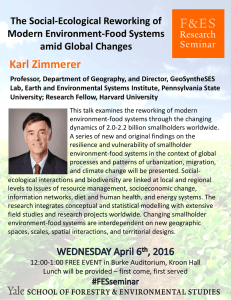

advertisement

COP 20 Briefing Paper: The Crucial Role of Smallholder Farmers for Food Security and Eliminating Poverty in a Changing Climate The population is growing – there will be 9 billion globally by 2050 – and the climate is changing. Around seven out of ten people, nearly 4.7 billion, are fed with food provided locally, mostly by smallholder farms, fishing or herding. There is an urgent need to improve the ability of farmers to produce more food whilst at the same time adapting to a more variable and changing climate. The application of the principles of agroecology1 is a practical and equitable way of doing that, especially for smallholder farmers. Most donors and agribusinesses are encouraging governments and investment in agriculture using high-tech intensive mechanisation to increase productivity – i.e. intensive monoculture. Industrialised monoculture is dependent on fossil fuels to achieve its high yields. This is not sustainable – not in terms of soil fertility and productivity, nor in terms of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and mitigating climate change. Policies and programmes that promote intensification using new technologies and loans tend to bypass or further marginalise smallholder farmers, particularly women, who often have less equitable access to services and finance. Intensive input-based production has extra risks associated with the loans (debt), reliance on external services, technologies and markets. This is illogical, because smallholder farmers are uniquely placed to increase their productivity through agro-ecological practices which build on their local knowledge and relationship with the land and environment. Practical Action believes there should be: A reorientation of agricultural research and development: - towards agro-ecology suited to resource poor and risk adverse smallholders innovation practices which cogenerate appropriate technologies with smallholder farmers incentives for private sector research and investment in low-carbon production practices regulation to safeguard agricultural biodiversity and negative environmental impacts Recognition of the crucial role smallholder farming systems play as part of the solution for national and global food securities - this includes recognition of the social benefits that incremental improvements in smallholder farming can provide (e.g. nutritious food and income security for the rural households) A change in the policy environment to promote agro-ecological practices - 1 improving the inclusion of smallholder farmers, particularly women, in market systems, and incentives for agro-ecological services, inputs and products support for private-sector delivery of agro-ecological extension services which promote sustainable and profitable long-term business practices The application of ecological concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agro-ecosystems We believe that promoting the principles of Technology Justice2 is fundamental to achieving food security and eliminating poverty in a changing climate. Currently commercial and industrial interests dominate global investment in agricultural research and innovation. As a result most agricultural research and development fails to include small-scale producers and overlooks both their needs and knowledge. The issues 1. The unique potential of smallholder farmers, especially women and indigenous communities, to adapt to climate change, and deliver food where it is needed most (children and famine prone areas), is not being sufficiently recognised in climate policy. 2. Smallholder farmers are the traditional custodians of the land and biodiversity – a role and right which is not being safeguarded, recognised nor remunerated. 3. The current emphasis on serving the needs of large scale agri-business means that poor and vulnerable smallholder farmers are often bypassed or further marginalised. 4. Research and development is skewed towards commercial input-dependent monoculture. This bias is reinforced by both research financing and career incentives for researchers. 5. Our financial and market systems do not support investment by smallholder farmers in low-cost and low-risk improvement in their production systems. 6. Liberalisation of trade in staple foods has undermined domestic markets and national food security. It also favours the financial viability of large scale production. 7. The demand for cheap food for urban populations is being used as an excuse to expand the highly lucrative system of mechanised mono-culture of a limited number of crops subsidised by fossil fuels. Such production systems are not sustainable and are exacerbating climate change. Policy makers need to recognise and address these issues and ensure the Global North meets its mitigation commitments and addresses the causes of climate change; and the Global South improves its agricultural productivity through better use of existing capacity and resources, including smallholder farmers, so they benefit from agriculture and adapt to changing climates whilst contributing to national food security. 2 The right to access the technologies one needs to live the life one values, so long as that does not prevent others now, or in the future, from doing the same 2 Smallholder farmers are essential for the global food system Most developing countries already depend on smallholder farmers for national food security. 80% of all Africa's farms are small plots, yet contribute as much as 80% of food production (IFAD, 2014). It is our experience in over 15 countries spanning Africa, Asia and Latin America that the local knowledge and manageable farm size of smallholder farms makes them well placed to use sustainable ecological approaches to produce food and, with assistance to develop their knowledge and experience, adapt to climate change. Smallholder farmers have a repository of indigenous and local knowledge which is vital for climate resilient agriculture, for example: o Improvement of informal seed systems will ensure supply of traditional varieties which provide choice and options for farmers to adapt to the changing climate and associated stresses, and to provide nutritious food. o Pastoralists and indigenous communities have maintained an extensive range of breeds and have the knowledge and skills to survive droughts and changing climates. o Local and indigenous knowledge of crops, livestock, forests and fisheries are resources that can enable production to be optimised in a sustainable manner that is consistent with the local carrying capacity and conditions. Empowering smallholder farmers to better use the land, agricultural biodiversity and knowledge (skills and practices) they already possess enables them to improve their situation and, at the same time, make a valuable contribution to local and national food security. It enables them to become part of the solution to extreme poverty, food insecurity and climate change, rather than part of the problem. Improved adaptation by smallholder farmers will reduce soil degradation caused by extractive farming. It will improve productivity and increase the attractiveness of agriculture for the young. If the private sector invests in agro-ecological services, inputs and products, soil degradation can be reduced with longterm benefits for business resulting from increased and sustained productivity of land. If smallholder farmers can increase productivity and provide their own households with more secure and nutritious diets, then health and the productivity of labour will be increased. Policy makers need to make the case for better food quality and long-term security which will improve the resilience of rural populations to hazards and shocks to Case Study: Farmer Field Schools in Nepal and Bangladesh Across Bangladesh and Nepal, over 70% of farmers live and work on small plots, often in marginal areas. Most are under threat from the impacts of climate change, including severe droughts and flooding. Practical Action has worked to build agro-ecological practices and technologies into existing farming practices with over 50,000 smallholder farmers. Farmers appraise the effects of climate change and share knowledge, information, skills and practices with other farmers and technicians who can provide additional information on how they might respond. Farmers and extension workers adapt technologies to meet the changing needs of each community. Field schools have implemented Integrated Pest Management, mulching, bund cultivation in saline areas, intercropping, alternate wetting and drying in drought affected areas (SRI), floating bed cultivation, and much more. Adaptation processes have been able to improve the resilience, quality and yields of land in areas where intensive mechanised monoculture practices would fail to be effective, efficient and sustainable. 3 their farming systems. Why agro-ecological farming is needed for food security and adaptation Most of the extreme poor live in rural areas. This is why developing countries need national policies to improve the rural economy, domestic markets and returns on agriculture for the poor. Supporting smallholder farmers should be a major part of government strategies to eliminate poverty. This is why smallholder rural farmers need fair market systems and information on agro-ecology to improve their ability to make technology choices. Improvement of farming through ecological, low-external-input practices can enable the very large number of poor rural households to derive reliable benefits and returns from their agricultural activities. Low-externalinput farming using agro-ecological practices can improve food security, incomes and livelihoods for households that cannot “step-up” through intensification of commercial production, or “step out” through leaving agriculture for employment in other sectors. Evidence is accumulating that fossil fuel based intensification (using mechanisation, inorganic fertilisers and pesticides) is fragile, with short-lived improvements that often decline in time with long-term detriment to the physical environment. Furthermore, mechanisation, agrochemical and finance based approaches to increase production tend to benefit the more financially secure medium and large scale farmers who are mostly men. In contrast, agro-ecological approaches are more accessible to the poor and women and therefore can create improved opportunities for vulnerable or female headed households. What is needed to make smallholder farming successful at scale? Agro-ecological practices can help farmers minimise the chance of crop failure. Participatory approaches can facilitate the combination of scientific knowledge with existing local and indigenous knowledge, and disseminate knowledge effectively where it is most needed. They can enable farmers to gain the skills and confidence they need to experiment and analyse options for adapting to climate change and improving productivity. But this is not sufficient to make sustainable returns from farming. Farmers need equitable access to markets so they can innovate and use their productivity to improve their financial security and physical assets. Similarly, production technology and inclusive markets are not enough for resilience. Farmers also need to be able to plan for, and cope with, external shocks and disasters. National governments and the international community should take a systems approach to create policies and incentives for achieving Technology Justice in agriculture so that research and innovation funding is channelled towards addressing social and environmental needs. 1. Policies to build farmer capacity to improve agriculture through optimising natural systems, rather than intensification of commercial monoculture to control natural systems. 2. Strategies to improve farmer organisations and institutions to enhance their bargaining power, collectively access inputs or services (e.g. finances, weather forecasts, insurance, market & technical information). Also to collectively market their products, thus delivering the benefits of small-scale production at the scale necessary for commercial market access. 3. Innovation in appropriate technologies. Policies and practices which support and facilitate the development of technologies appropriate for smallholder farmers to make the best use of the land and for pastoralists to best tend to their animals. Policies are needed to enable open access to these technologies and to ensure they are developed in cooperation with local communities. 4. Investment in knowledge systems that connect formal sources of knowledge (e.g. National Agriculture Research Systems and Meteorological Services) to indigenous and local knowledge of 4 farmers and communities and to consolidate learning. ‘Knowledge systems’ include the building of capacity to make decisions and services to support the provision and use of information. 5. Build the capacity of governments, development agencies and agricultural service providers to facilitate inclusive markets – i.e. create markets that work for the poor. In the short term this includes ensuring an enabling investment environment for agro-ecological and low-external input practices targeted at smallholder farmers, particularly women. 6. National and international policies that encourage production for local and domestic markets. This requires governments to address the inequalities in the global markets so small scale and large scale producers compete equally. This is a difficult and long-term challenge as it requires the removal of subsidies, unfair taxation and tariffs. International trade agreements should consider the environmental impacts of large scale production and transportation. Such externalities act like subsidies and should be included in the cost of production. The role of companies in an economy is to improve efficiency and innovation. In agriculture this should not simply mean reducing costs (e.g. using fossil fuels to achieve economies of scale). Policies should be in place so that efficiency in agricultural business includes sustainability. Case Study: Integrated Water Resource Management in Sudan Eighty percent of the population in Sudan rely on natural resources for farming, herding and agricultural trade. Deepening cycles of drought are destroying the traditional rain-fed livelihoods and affecting groundwater availability. This has led to increasing labour demands for water collection by women as they are forced to travel to more distant locations. Practical Action has integrated agro-ecological technologies into existing practices 25,000 with Relevance to the UNFCCC: mitigation, adaptation, and loss & damage The effects of climate change are already being felt by the most marginalised communities. Adaptation to these conditions is necessary for these populations to thrive. We are advocating for an urgent commitment by the international community and private sector to fund adaptation. over smallholder farmers and pastoralists. Building upon traditional ways of coping with arid conditions, including use of man-made reservoirs (hafirs), Practical Action has developed technologies with communities to improve water security and achieve higher market prices. Technologies included ‘cut-and-carry’ Wadi-based animal feeding systems for livestock and the ability to secure higher market prices, and sluiceways to protect the larger earth dam structures to control silt and water flows during periods of heavy rains. These innovations are integrated with community institution building and participatory methods to mitigate conflict over scarce resources and build lasting peace in an increasingly pressured physical environment. By building upon and enhancing traditional systems, Sudanese farmers have adopted new technologies and see the benefits of agro-ecology. 5 Secondly, we recommend that a significant proportion of the public sector climate funds should be allocated to Loss & Damage. The international community should recognise that for many of the most vulnerable, the impacts of climate change are irreversible and it is too late to adapt. Therefore we insist on political and financial commitments to support these people to relocate and rebuild their livelihoods. Lastly, we implore all governments to take Mitigation seriously and do more to reduce the level of GHG emissions to combat climate change. We believe this should be achieved through reform of legislation and economic systems so that mitigation is financed by the private sector – i.e. a polluter pays principle. This would incentivise a global reconfiguration of our food energy systems that would reduce the need for adaptation or loss & damage by future generations. For example, progressive consumption tax based on the pollution index of products could incentivise changes in consumption. Conclusions Climate change is going to exacerbate the food insecurity that is already affecting many parts of the developing world. It will reduce productivity through increasing incidence of drought, unpredictable seasons, extreme events and other impacts on our crop, livestock and fisheries production systems. To respond to the threat of climate change Practical Action advocates for a global food system that includes smallholder farmers. Smallholder farmers offer the opportunity to optimise production in a sustainable manner, based on local conditions. They offer a degree of diversity and ability to manage the local environment to minimise the negative impacts of climate change, to maximise production opportunities and promote strategies for eliminating poverty. Strengthening the way smallholder farmers use their resources can provide developing country governments with robust local production systems for food, fibre and fuel that are consistent with the carrying capacity and attuned to the local climate. It would increase production where it is needed most, strengthening food security, raising incomes, generating employment, and manage the landscape in a way that creates multiple benefits – adaptation, mitigation, food security and poverty reduction. Improving the role and productivity of smallholder farmers will also deliver social benefits – strengthening rural communities – and counter incentives for migration to urban centres. National governments and the international community should create policies and incentives for achieving Technology Justice in agriculture so that research and innovation funding is channelled towards addressing social and environmental needs, in collaboration with smallholder farmers. To achieve mitigation and adaptation the global food system needs to be transformed to rely on lowexternal-input production systems that optimise nature to improve productivity and ensure that natural resources are available for future generations. This can only be achieved by acknowledging and supporting the crucial role of smallholder farmers through food, agriculture and climate policy. References / Further Reading - State of Food Insecurity in the World 2014, FAO http://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/2014/en/ ETC Group (2009) ‘Who will feed us?’ Communiqué Issue 102 http://www.etcgroup.org/content/who-will-feed-us Agroecology - What it is and what it has to offer, IIED (2014) http://pubs.iied.org/14629IIED.html Participatory Market Systems Development (PMSD) for facilitating inclusive (pro-poor) markets http://practicalaction.org/transforming-market-systems Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Fifth Assessment Report, 2013-2014, http://www.ipcc.ch/index.htm The International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD), Agriculture at a Crossroads (2009) http://www.unep.org/dewa/Assessments/Ecosystems/IAASTD/tabid/105853/Default.aspx/ 6 For further information, please contact Mr Chris Henderson, Senior Policy and Practice Advisor – Agriculture, policy@practicalaction.org.uk http://practicalaction.org/food-agriculture-policy Practical Action, The Schumacher Centre, Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire, CV23 9QZ, UK 12th November 2014 7