(-2po§) 'V^ 2.18 The Transformation of the Eighteenth

advertisement

e

(-2po§) 'V^

2.18

The Transformation of the Eighteenth

Century

The Sened-i ittifak: 1808

More than half a century passed between the revolts of the

1730s and 1740s' to the coup d’etat of 1807—1808 against Seiim

III - a reformist sultan - which was the third event that

shook the relative calm of Istanbul. The coup against the

sultan brought the best men of the provinces to the imperial

center, the first such case of direct intervention from the

provinces. The renowned notable Alemdar (or Bayraktar) Mustafa

Pasha arrived in Istanbul with his provincial army to restore

Selim EH to his throne, and became instrumental instead in the

establishment of Mahmud II. I return to these tumultuous

events in the capital after briefly reviewing the antecedents

that brought the periphery to the center.

In the post-Tulip period, two crucial developments came to

maturation. First, the fiscal system of the late seventeenth

century - initiated to collect money for the treasury altered traditional sources of income into life-term tax

farming, opening the way for the purchase of numerous sources

of revenue by private individuals alone or in association with

others. Life-term tax farming empowered a wealthy set of

Istanbul elites and bureaucrats who bought these tax farms in

the provinces, but farmed them out to provincial notables

(ayan), who became their astute local entrepreneurs. Locally,

these notables managed to take over both the lands and the

administrative functions of the traditional elite, also

currying favor with the state to assume important revenuecollecting positions. From the modest local notables who

acquired positions and served the state loyally to the wealthy

and powerful notables who threatened the local rule of the

state, the provinces were strewn with these new landholders

and tax collectors.41 They developed their own households,

patronage systems, local political culture, and local armies,

which they headed to help the sultan at war when they felt so

inclined.

Second, with the impact of a new world of trade engaging

especially the western shores of the empire, these local

notables and administrators became emboldened turning their

tax farming into commercial enterprises, poised to profit.

Internal fiscal reform and external commercial opportunities

altered the social and administrative landscape of the

provinces. The traditional forces of administration and

taxation, the provincial landholding system and its managers,

and the timar holders were disappearing. The traditional

functions of the state in the provinces were now taken over by

these increasingly powerful local notables, who were organized

as extended regional networks of family^ kinship, and

patronage ties, ensconced in the changing structure of land

tenure and commercial expansion. The 1808 Agreement (Sened-i

Ittifak) was the fin- de-siecle episode of the most powerful

among these men arriving in Istanbul to sign a political

document of state—notable truce and cooperation, following

their comrade from Rumelia, Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha.

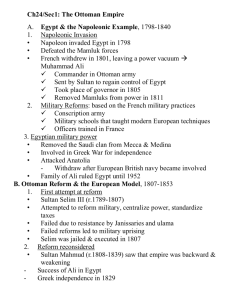

At the center, Selim HI (1789-1807) had come to power at a

moment when the peripheries of the empire, both the near

periphery of the Balkans and the

4i Chapter 7 is devoted to an analysts of these state-society

processes.

2.1<j

An Eventful Eighteenth Century: Empowering the Political

farther Arab provinces, were feeling the tension between the

administration of the state and that of the local notables.

Rumblings of regional rebejionsjox autonomy emerged. In the

Balkans, the notables were competing for territory and

influence, often bringing the state into their local

struggles. Local rule by the agents of the center was

increasingly varied: weakening in certain areas while steady

and strong in others. For example, in the Serbian provinces,

the janissaries ran amok, but in the Bosnian provinces, law

and order prevailed due to good central-local administration

43 Yet, within this widespread variation of rule, movements

for autonomy such as that of the Serbs and the Greeks emerged.

In other regions, the near separation of Egypt, Syria, and

Iraq became of vital importance. It is in this- atmosphere

that Selim m commenced a series of reforms, the most important

of which was organized around the military. Selim m worked on

the reorganization of a new military in comparative secrecy

with the knowledge of a few reformer administrators; this

indicated that they were worried about the potential reaction

of the conservative Janissary forces and the ulema. For both

groups, such reforms represented threats to the traditional

order. Furthermore, that Selim was able to replenish his new

army with so diers and resources from among the provincial

armies also demonstrates that there were among the powerful

notables those who supported the new

young sultan in his endeavor to reform the more traditional

and reactionary forces at the center.44

A delicate and precarious balance between opponents and

supporters of SelimJs regime ensued as enemies of reform

multiplied in the provinces and in Istanbul. The Ottomans had

forever promoted power struggles on the periphery under the

belief that local and regional struggles for control between

different powerful notables was healthy and would deflect

opposition to the state. At the same time, they also used

armies of notables for the protection of the provinces and as

another reserve of military recruits during war. The

unintended consequence of such policies was that when a

notable accumulated local power and military might and decided

to turn against the state, he could cause significant damage

to the empure. Complicating Selim’s reform initiatives further

was the Russian movement into the Danubian principalities in

1806, the culmination of Russian interference in the affairs

of the Christian population of the Balkans, where they

fomented discontent and also created alliances with the Muslim

magnates of the periphery, especially in Egypt and northern

Anatolia.

In the capital, the supporters and the enemies of reform

battled among themselves until a coup led by the Janissaries

supported by the ulema gave the upper hand to the enemies of

reform. The coup was achieved on 2.5 May

44 r ^ ^icl<olc’ °ttorna'n Military Administration in EighteenthCentury Bosnia.

smail Hakki UmnCarsiii,Me$hur Rumeli Ayanlanndan Tirsinikli

Ismail, Yihk Oglu Suleyman

OlcUndN^biil: M^Matbaaa, i94z); Stanford J. Shaw, Between

Old and The Ottoman Empire under Sultan Seltm III, j789-i8o7

(Cambridge MA2.2,0

The Transformation of the Eighteenth Century

1807, when the reformer Raif Ivlahmud Pasha went to the

headquarters of the old yamak troops to pay their salaries and

to urge them to join the new army created by Selim III and his

men. Instead, the soldiers savagely killed the pasha. The

conservative forces fighting against change were at the

forefront of the coup; the Janissaries were afraid that the

new army, the Nizam-i Cedid, was going to put them out of

business; the ulema, meanwhile, steadfastly believed in the

evils of European influence in reform. By z8 May, various

contingents of the Istanbul military forces were having Ka

spirited debate over the legality of their actions,” before

all agreeing to join the rebellion at the Janissary barracks.45

Many reformers were executed, the reforms abolished, and,

finally, only after the tensions and the hazards of keeping

Selim HI as sultan mounted, he was dethroned to make way for

Mustafa IV on 2,9 May 1807.

This rebellion and treachery of the Janissaries launched a

coordinated response from the provinces, an alliance of the

ayan of Rumelia and Anatolia marching in unison under the

leadership of Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha, the most powerful

notable of Ottoman Europe. The political divisions in

Istanbul, the coup against Selim HI, the ruin in the Balkans,

and the increasing threat of the Russians came together to

propel responsible notables into action. In the chaos of the

palace and the confrontation between the new sultan and the

leader of the provinces, Selim HI was assassinated, thus

depriving the counter-coup forces of their most important

asset. The provincial leaders reacted quickly to install

instead Mahmud 31 (1808-1839) to the throne, removing Mustafa

for his younger cousin. Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha became the

grand vizier of the new sultan and proceeded once again to

gather reformers around him. From July to November 1808,

Bayraktar remained the dominant force in the empire. Soon

after becoming grand vizier, he appealed to his provincial

comrades to come to the capital for a special session

(me§veret-i amme) to discuss the affairs of the state. That he

invited his former colleagues to this assembly is interesting

in itself because it demonstrates the realization by a man of

the provinces of the need to coopt the provinces into a

project of the center. From this extraordinary meeting emerged

the document entitled “Sened-i Ittifak,” a political agreement

between state and provincial magnates.

The Sened-i Ittifak (literally, a deed of alliance or a

concord) was the first of its kind in political deal making in

the Ottoman Empire. The Sened was the political culmination of

the provincial march on Istanbul, yet was negotiated within

the context of strong state and societal actors. Those

historians who have emphasized the power of the ayan to the

detriment of the state have a tendency to see the end point of

this century — the takeover by Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha and the

1808 Sened-i Ittifak - as catastrophic for state affairs. They

see these events as heralding a serious loss of state power,

and especially for those historians interested in nationalism,

this historical moment signals a green light for

local/regional movements of self-determination. Others argue

45 Shaw, Between Old and New, 380.

An Eventful Eighteenth Century: Empowering the Political

2.2.X

for the relative insignificance of the event/6 The Sened-i

Ittifak represented a pact signed between the state and the

ayan with respect to their mutual responsibilities. In fact,

careful study of the documents related to the pact provides us

with an alternative explanation of centralization, espoused

especially by one Turkish scholar, I. H. Uzun^ar§ili, who

claims that the Grand Vizier Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha strove to

centralize the empire. I agree that reassembling these

important nodes of local power under state supervision would

certainly be a goal of centralization.

Centralization was necessary to reassert control over

European provinces. Prior to the reign of Selim HI, especially

the European parts of the empire had plunged into anarchy. In

the 1790s, the infamous notable Pasvanoglu rebelled against

the Ottoman state and its military reforms; many ayan operated

rebellious armies and with the increasing presence of bandits,

Macedonia and Thrace had fallen into complete disarray.47

Centralization was also necessary to pull in as many local

power holders as possible, reaffirming their role as agents of

the state. Among them, those who opposed the reforms of the

state perceived the efforts at centralization and the creation

of alternative armies as a direct threat to their well—

established provincial rights and privileges. Certainly the

relationship between the state and the ayan of Vidin,

Pasvanoglu, suggests that the animosity was the result of the

state’s attempt to forge alternative sources of regional power

in the provinces. Others however, in Rumelia and many in

Anatolia had forged alliances with the state and remained

loyal. Among those in Rumelia, Tirsiniklioglu promoted Selim

El’s reforms, and Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha - despite some early

hesitation, especially during the Russian

4

Itzkowitz, for example, delineates the eighteenth

century with two events; the 1703

Edime rebellion and the 1808 Sened-i Ittifak. He interprets

the latter as one more deadly nail in the Ottoman state’s

coffin, whereby a weak state made an agreement with strong

feudal interests. Furthermore, in his view, this agreement is

the first time old Islamic traditions of government and

society were forever altered. See Norman Itzkowitz, “Men and

Ideas in the Eighteenth Century Ottoman Empire,” in Studies in

Eighteenth-Century Islamic History, ed. Thomas Naff and Roger

Owen {Caxbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977)

15-2.6 Furthermore, whereas both Halil Inalcik and Kemal

Karpat wrote early on about the Sened-i “ much more balanced

terms, they have been ignored. See Halil kalcik, “Sened-i

Ittifak ve Giilhane Hatt-i Hiknayunu,” Belleten 2.8 (October

1964): 603-690; Kemal Karpat, “The J-and Regime, Social

Structure and Modernization in the Ottoman Empire,” in

Beginnings of Modernization in the Middle East, ed. William R.

Polk and Richard L. Chambers (Chicago- The University of

Chicago Press, 1968), 69-90; idem, “The Transformation of the

Ottoman State 1789-1908, International Journal of Middle

Eastern Studies 3 (1971); 143-281. §erif Mardm barely points

to the r8o8 pact, en passant in a footnote, declaring it to be

“a burst of seif- assertiveness on the part of the Ayans.” See

§erif Mardm, “Power, Civil Society, and Culture in the Ottoman

Empire,” Comparative Studies in Society and History n (1969):

178-179 n. 2 or another overview of the historical events

leading up to the pact and a description of the discussions

around the pact, see Uzunfarjui, Meghur Rumeli Ayanlanndan

Tirsinikli Ismail.

°Ve™£ /*“ ^ M““5’ « DM* S.** “Urban Notables in tic , .

dissertation, Rutgers University, New

Brunswick, NJ,

nIZJSZfig ff^~f“““ Coips “ H,h“h Cra”ry'"

12 2

The Transformation of the Eighteenth Century

campaigns - had come around to supporting the sultan. In

Anatolia, among the most significant supporters of the reforms

were the ayan with. the_most power and wealth, Karaosmanoglu

and £apanoglu.48 Therefore, by the end of Selim Hi’s reign,

despite the varying allegiances in the Balkans and Anatolia,

there were still key notables who had tied their fortunes to

those of the sultan. And for those men, there was no

substitute.

These regional men were key to reestablishing order at the

center. Their intervention at the center of imperial politics

did not result in a takeover by the ayan\ on the contrary, it

was an act of loyalty to the state whereby they tried to

reinforce the order they perceived to be legitimate. When

Selim HI was dethroned, Bayraktar and his friends/fellow ayan

“Les Amis de Roustchouk,” as Miller calls them, went to

Istanbul in 1807-1808 to redress the situation, reinstate

Selim m, and help him revitalize his reforms. They were

organizing, in effect, a counter—coup in support of the

Sultan, but against those who wanted a change in government.

When the sultan was executed at the hands of the conservative

alliance, Bayraktar put the young Mahmud II on the throne and

took over the affairs of the state as the new grand vizier.

His intention was to unite the provincial elements with the

reformists in Istanbul, and thereby strengthen the reign of

Mahmud II. The Sened-i Ittifak was the pact that resulted when

Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha, the new grand vizier, convened all of

the large ayan of Rumelia and Anatolia. Not many came, but

those who did were among the most powerful ayan of Rumelia and

Anatolia, the brokers who held state positions and wielded

great local power. Despite their known allegiance to the

Ottoman state, these ayan showed up with their private armies,

ready for all eventualities.49 The result of many days of

deliberations was a pledge of loyalty to the Ottoman state and

an agreement to remain on the course of reform, and therefore

to back the reformists within the government. In return, the

ayan got a promise of autonomy only in the sense that they

were now fully recognized as regional powers, respected in

their positions, and provided with a sense of freedom of

action.

The original speech by Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha both provided

an explanation for interference from the periphery and put the

actions of the ayan into context. Bayraktar justified the

rebellious attitudes of the ayan during the reign of Selim El

and presented their presence at the court as an act of

generosity toward the state and Islam. The warriors of Islam,

he argued, had become

4 Shaw tells us that Karaosmanoglu supported Selim El and his

Nizam-i Cedid army not only by supplying money and men to

the corps in Istanbul, but also by accepting officers to

train his men in the new forms of warfare. Similarly,

£apanoglu engaged in Nizain-i Cedid formation and support.

Stanford J. Shaw, Between Old and New: The Ottoman Empire

under Sultan Selim III, 1789-1807 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1971), 2.15.

45 Uzungargiii counts seven ayan at the events: the ayan from

Bilecik, KaJyoncu Mustafa; the ayan from Manisa,

Karaosmanoglu Omer Aga: gapanoglu Suleyman Bey; the ayan of

§ile, Ahmed Aga; the voyvoda of Bolu, Haci Ahmedoglu Seyid

Ibrahim Aga; the ayan of Serres, Ismail Bey; and the ayan of

Airmen, Mustafa Bey. See Uzunfarjili, Me$hur Rumeli

Ayanlanndan Tirsinikli Ismail, 13 S. These men were

supporters of state policy.

An Eventful Eighteenth Century: Empowering the Political

2,2.3

weakened and had to unite in order to glorify the faith and

the empire. The

general tone was that these actions were for the “good of the

state,” rather

than in the interests of the ayan.^ However, the language and

the spxritofthe"

speech were regional; Bayraktar addressed the ayan in their

language and style

and appealed to their popular understanding. Consequently, he

successfully

brought into the fold of the state those who clearly stood at

the interface of

state and society, and sent them back out again to preach

order and incorporation. 1

The text of the agreement certainly confirms the sense that

the strength of the

state was preserved and that the ayan were given what they had

already wrested

for themselves. The 1808 agreement has often superficially

been compared to

the Magna Carta; however, this is erroneous. Unlike the Magna

Carta of

12,15, in which the king was assailed by numerous grievances

by the nobles,

the Ottoman document shows no such contentious spirit. It is

also incorrect to

assume that the Sened-i Ittifak was the direct result of the

struggles between

state and notables. Conflict between these state and societal

actors existed,

yet those notables who came to Istanbul were in agreement with

the state; that

is, they were not its real opponents.51 It is also worth

looking at the beginning

of these documents, especially the Ottoman one that starts

with an appreciation

of the institution of the state, and the English document that

asserts the freedom

and liberty of the church and all free men. That the Ottoman

document started

by underlining the special place of the sultan and the state,

the importance

o the protection of the state, and the need for submission to

the authority

of the sultan and the grand vizier was indicative of the

centralization agenda.

The benefits for the central state were apparent: the

reinforcement of the new

armies; the phasing out of the Janissaries by decreasing their

salaries even

further, thereby giving them practically no choice but to join

the new military

units and retrain; and financial repackaging of some taxes for

further military

use. The center had furthermore succeeded to appeal to the

periphery, forcing it to retrain itself.

For the notables, the pact did not represent much change in

their practices. The ayan who^ participated in this meeting

were already the most important ones, and had in many

different ways ensured that their sons and - even more

consequential - their larger kinship network enjoyed the

privileges of their dominant positions after they had passed

away. In practice, they had already established a kind of

“feudality.”^ They had informally established rights

5° ^ZUnfr^. Pro^d« the complete text of this speech. See

Uzunfarfili, Me$hur Rumeli Ayan- lanndan Ttrsintkh Ismail,

141-142.. For a French translation, see A. F. Miller, who

presents segments of the speech given by Bayraktar at the

opening session of the conference of ayan See Miller, Mustapha

Pacha Bairaktar, 312,-31351 See Footnote 48.

51 5?’ f°r fxamPIe’ varl0US discussions of the Karaosmanoglu family

of western AnatoEa. They did riot directly relinquish their

posts to their sons, but they ensured the prominence of

their family m key administrative posts. The brothers and

sons of Mustafa Aga, for example mamtamed posts m the region

and struggled to keep these titles against other ayan.

’

The Transformation of the Eighteenth Century

and privileges over weaker and smaller ayan. These

prerogatives were often enacted through the alliance of a few

strong ayan pooling their resources, to subordinate others.53

As I show in Chapter 7, the notables who had come to Istanbul

to throw their support to the grand vizier and the young

sultan were well established. They had little to fear. They

had woven strong horizontal networks of association and

vertical lines of patronage that both protected them from

above among the grandees of the state and created exploitative

networks of production. Nothing in the agreement gave these

men new powers. All the Sened-i Ittifak did was encode this

power in more public ways.

Yet, this agreement between state and notables was quite

significant in other ways. It unmistakably represented a shift

from a pattern of deal making between the state and the

individual notable family to deal making between the state and

a group of elites, who seemingly acted in concert. The main

advantage to the ayan was not the concessions the state made,

but rather their recognition of the efficacy of concerted

action. For the first time, the ayan understood that they

could act in unison and were empowered by the show of force

that they had inadvertently demonstrated. By calling them to

Istanbul, the grand vizier had opened the door for collective

bargaining, a circumstance without much precedent in Ottoman

history. As the notables came to the collective realization of

the power of the message sent by thousands of men gathered at

the doors of Istanbul, awaiting orders from their masters, the

ayan, Mahmud II also understood the significance of such joint

action of resistance to the state. Then and there must have

come his resolve that the state could very well act to

retrieve these privileges by waging war on the ayan. He showed

much reluctance to sign the Sened document. Soon after, Sultan

Mahmud II would reassert his and the state’s power by waging

war first against the most visible and the most powerful of

the ayan, Ali Pasha of Janina (Tepedelenli).

Given such an analysis of the events that led up to the

reign of Mahmud II and the pact with the ayan, it is difficult

to interpret this history as one of decentralization. The

Sened-i Ittifak was a prelude to the much stronger efforts of

consolidation of the nineteenth century. It represented an

important attempt to convince those regional brokers most

likely to be convinced, and to establish a covenant enabling

reforms to be carried out with relative peace and quiet. For

the state then, the Sened-i Ittifak may not have been a

complete political victory, but certainly it was a political

act of consolidation. For the ayan, the Sened-i Ittifak also

was not a political victory, but an event that demonstrated

their potential relational power. The peripheral elites had

come to the center, empowered by horizontal ties, but saw

their interest anew in bolstering central power over which

they now had much sway.

It is said that Tirsmikliopu Ismail Aga of Rus^uk had allied

with Osman Pasha Pasvanoglu of

Vidin in a regional coalition to ensure themselves the role

of appointing ayan to positions in

their regions, thereby constructing their own patronage

networks.

An Eventful Eighteenth Century: Empowering the Political

Z25

Conclusion

From 1703 to 1730 to 1808, the unfolding of the eighteenth

century tells an important story of political empowerment, of

societal forces at different moments in different alliances

forging an opposition to the state that saw its goa as reform.

Reform, however, was defined in multiple ways through the

course of this history. It came to mean a return to the old

Siileymanic age as well as just its opposite, an

acknowledgment of the need to espouse Western knowledge and

practices. The meaning of reform very much depended on the

forces trying to control state politics. When it was the

Janissaries and ulema at the helm of opposition, reform was a

return to the social and political order of the classical age

as defined by the actors themselves. It conceived of bounded

institutions, separation of realms and groups in society, and

the reinstitution of imperial notions of conquest and

territoriality. At the hands of such conservative religious

forces, an increasingly narrow Sunni orthodoxy would be

protected and perfected by the increasingly centralized

institution of the ilmiyye. In contrast, reform at the hands

of Selim IE, Mahmud II, and the powerful interlocutors of the

state in regional politics meant continued flexibility at

adapting and absorbing new developments, perhaps beyond a

continued understanding of institutional continuity between

the Ottomans and the West. In these contrasting views of

reform, we have to conclude that an important segment of the

provincial elites of 1808 acted in concert to stop the

reactionaries at the center, and, as such, they made possible

another round of more important reforms that were to be

carried out by Mahmud II, the Tanzimat. Notables then proved

to be the more flexible element of the empire at this moment,

struggling against those who resisted change and adaptation.

Chapter 7 further clarifies the reasons behind the pragmatism

of this new class of actors. In the eighteenth century, these

actors had acquired the capability for important economic and

social growth and development, and it seemed to be in their

interest to maintain the order that provided them with such

privilege.

Erik 3. Ziircher. TURKEY: A Modern History

TURKEY

A Modem History

LR1KJ. ZURCHLR

l.RTauris & Co Ltd Publishers London • New York

Erik 3. Ziircher. TURKEY: A Modern History

3* The Early Years of Sultan Mahmut II: the centre tries to

regain control

Mahmut II had been a witness both to the limited successes of

the Nizam-1 Cedid and to the fall and death of his cousin

Selim. He seems to have learnt his lessons well and also to

have been a much more adept tactician. He started from an

extremely weak position. He had been put into power by the

Bayraktar, who himself was no longer there, and the only

reason Mahmut II was left on the throne was that there was no

other male successor available. He therefore had to move

circumspectly and spent the first 15 years of his reign

establishing a power base. This meant appointing trusted

supporters to key positions in the scribal service, the ulema

hierarchy and the army. His second aim was the reduction of

the semi-independent ayan who had brought him to power. This

he to a large extent accomplished. Between 1812 and 1817 the

major Anatolian notables were brought under control, and

between 1814 and 1820 the same happened in the Balkans. In

Kurdistan the process took longer, but there too the power of

the practically independent Kurdish princes, the Min who had

ruled over large tribal coalitions, was eventually broken.

Here, the existing triba! structure of society meant that the

removal of the princes and the inability of the central

Ottoman government to replace them with effective central

control led to a long period of anarchy, in which authority

reverted to the tribal chiefs and to the religious leaders who

built up their authority as mediators in inter-tribal

conflicts. In the Arab provinces the restoration of Ottoman

government authority over the notables took place only later,

in the 1840s.

The methods employed in subduing the ayan, in the age-old

Ottoman tradition, were peaceful where possible (bribes were

given,

THE EARLY YEARS OF SULTAN MAHMUT II

33

hostages taken, divisions among the notables ably exploited).

Open warfare was used only as a last resort, and then it was

that of the traditional military establishment: mainly the

Janissaries. It is important to understand that, while the

sultan was slowly strengthening his hold on the government, he

had not yet broken with the scribal or military establishment.

While proponents of reform were put into more and more

important positions, the most powerful politician of these

early years of Mahmut’s reign was Halet Efendi, a member of

the ulema and former ambassador to Paris, with a generally

conservative outlook. He was close to the janissaries and his

efforts at, and success in, subjugating the ayan can be seen

as being motivated by a desire to strengthen the position of

the Janissary garrisons in the provinces, which were the great

competitors of the notables.

Lost territories: Serbia, Greece, Egypt

Mahmut and his servants succeeded in re-establishing control

over most of the central Ottoman lands, but in a few important

cases they failed. In 1804 the insurrection led by Kara George

broke out in Serbia against the excesses of the local

Janissaiy garrisons. The government of Selim III, engaged in

its own struggle with the Janissaries, had condoned the

insurrection, but after the elimination of the garrisons the

movement developed into one aimed at Serbian autonomy. In

spite of some modest Russian support for the Serbs, the

Ottoman army suppressed the movement in 1813. Two years later,

however, it flared up again and this time the new Serbian

leader, Milo$ Obrenovi£, reached agreement with the Ottomans

on autonomy for a Serbian principality between Belgrade and

Nish. The Ottomans retained the right to garrison the major

towns and to receive a yearly tribute (this, it should be

remembered, amounted to the same degree of influence as the

central government had enjoyed in, for instance, Kurdistan or

the Arab provinces in the eighteenth centuiy).

The Greek insurrection which broke out in 1821 was more

important for three reasons. First, the Greek community in the

empire played a crucial role in the empire’s external

relations, both economic and diplomatic. Second, from the very

beginning of the insurgency many of its leaders aimed at full

independence; and third, the crisis which ensued directly

involved all the major European powers.

The Philiki Hetairia, a Greek patriotic society founded in

Odessa in 1814, had been busy over the next few years founding

cells throughout the Balkans. Kara George was at one time a

member. From 1820

Erik J. Ziircher. TURKEY: A Modern History

34

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

the organization was led by Alexander Ipsilantis, a member of

one of the elite Phanariote (so-called after the Phanar

quarter in Istanbul) Greek families of the Ottoman Empire and

himself a general in the Russian army. In 1821 Ipsilantis and

his group considered the time ripe for a full-scale

insurrection, which they hoped to trigger by an invasion of

Moldavia and Wallachia {present-day Romania). Their aim was a

general rebellion in the Balkans, in order to create a new

Byzantine Empire under Greek leadership, and not merely a

Greek national state. The invasion which was supposed to bring

about the realization of this ambitious scheme was, however, a

disaster. The invading army was much too small (about 3000

men) and the peasant population in Moldavia and Wallachia was

never likely to side with the invaders, since the great

landowners and the governors of these provinces were

traditionally from the same Phanariote families from which

Ipsilantis stemmed. For their part, many of the influential

and rich Greek families of the Ottoman Empire actually opposed

the Hetairia's nationalist aspirations.

At the same time the invasion failed, another and veiy

different Greek insurrection began to spread in the

southernmost parts of the Balkan peninsula and on the Aegean

isles. Although the rebels were influenced by Hetairia

propaganda, it was a genuine popular revolt against Ottoman

misrule. The rebels were badly organized and divided amongst

themselves, but nevertheless the Ottoman army in 1821-4

signally failed to defeat them. By 1824 almost the whole of

the Morea (the Peloponnese) and many islands were in the hands

of the rebels. It has been argued that the success of the

rebellion was due in part to the fact that in 1820-22 the

Ottoman government was engaged in the military suppression of

the most powerful of all the Balkan notables, Ali Pasha of

Yannina. In removing him, they also removed the only force

which could effectively control the area.

The most important territory lost to the empire in this

period was the province of Egypt with about four million

inhabitants. This loss was the work of one man, the Ottoman

governor of Egypt, Mehmet Ali. In the years when Mahmut II was

gradually strengthening his hold on the government apparatus

by infiltrating it with his supporters, his governor in Egypt

demonstrated what effective concentration of all power at the

centre could accomplish. Mehmet Ali was an Albanian from

Kavalla (now in northern Greece), who had come to Egypt as an

officer in the Albanian contingent in the Ottoman

expeditionary force against the French, In 1803 he had become

the leader of that corps

THE EARLY YEARS OF SULTAN MAHMUT II

35

and had established himself as the de facto ruler of Egypt. In

1808, he was officially recognized as governor of Egypt by the

sultan.

The French occupation had fatally weakened the position of

the Mamluks, the part-Circassian, part-Turkish military ruling

elite of the country. They had been chased from lower Egypt by

the French and during the Napoleonic wars had been unable to

replenish their numbers by recruiting slaves in the areas

north of the Caucasus, as had been their practice for hundreds

of years. In a sense, therefore, the French occupation had

provided Mehmet Ali with a clean slate. He used this

opportunity to destroy the last vestiges of Mamluk power,

massacring their leaders in the Cairo citadel in 1811.

Thereafter, he embarked on an ambitious programme of reform

aimed at the strengthening of his government.

As with Selim Ill’s Nizam-i Cedid, the main element of the

programme was the creation of a large, modem, European-style

army. This brought with it the need for larger state income

through taxation, the need for a more efficient bureaucracy to

mobilize the resources of the country, and the need for modem

Westem-style education in order to create the cadres for the

new army and bureaucracy. The Ottoman reformers from Selim III

and Mahmut II onwards had faced the same dilemma; but they did

not have the advantage of a situation, such as Egypt’s, in

which the old establishment had been destroyed by outside

interference. Furthermore, Mehmet Ali took much more drastic

action than the early Ottoman reformers could or would

undertake to solve the two main problems which the

modernization of the army entailed: lack of income and lack of

dependable manpower from outside the military establishment

(the Janissaries and affiliated corps in the Ottoman case, the

Albanian forces and the Mamluks in Egypt). After some

experimenting, Mehmet Ali solved the manpower problem by a

radical innovation: the introduction of conscription in 1822.

The monetary problem was never completely solved, but Mehmet

Ali was much more successful than the Ottomans of his era in

increasing his income to pay for the expensive new army (and

fleet). He replaced the tax-farm system with direct taxation;

and he encouraged the development of agriculture, investing in

irrigation and roadworks and forcing the farmers to grow cash

crops, of which cotton became the mainstay of the Egyptian

economy. Also, Mehmet Ali enlarged the highly profitable state

monopolies precisely at the time when, as we shall see, the

Ottomans were forced to abandon them.

There can be no doubt that Mehmet Ali’s example was highly

Erik J. Ziircher. TURKEY: A Modern History

36

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

influential in Istanbul, both as an inspiration and as a

source of rivalry.

In the early years of his reign, the sultan in his weakened

position had

f

no choice but to apply for help to his most powerful subject,

first to fight

I

the fundamentalist Wahhabi movement among the tribes of

central

f

Arabia, which threatened the Ottoman hold on the holy places

of Islam,

Mecca and Medina, and in 1824 to help suppress the Greek

rebellion, something the Ottoman Janissary army was patendy

incapable of doing.

£

The last phase of the Greek rebellion, war with Russia again

At the request of the sultan’s government, Egyptian troops

landed in the Morea in 1825. Where the janissaries had failed,

they were highly successful and over the next two years they

conquered most of the mainland. Only the dominance of the

Greek merchant navy, which was able to supply the rebels with

arms and food, prevented a complete collapse of the rebellion.

In the face of military disaster, the Greek insurrection was

now saved by European intervention. There was a great deal of

sympathy with the Greek rebels in Europe, most of all in

Britain and in Russia. In Britain the sources of this

‘philhellenism’ were liberal sympathy for Greek national

aspirations and admiration for classical Greek civilization,

with which the modem inhabitants of the southern Balkans were

identified. In Russia, the main motive behind the sympathy for

the Greeks was religious solidarity within the Orthodox

church. This public sympathy with the rebels did not translate

into political support, except in one country: Russia.

Tsar Alexander J tried to get the other great powers of Europe

to agree to intervene in the conflict in support of the

establishment of an autonomous Greece. The other powers,

however, were not enthusiastic, fearing 'that an autonomous

Greece would become a Russian puppet state. Tsar Alexander,

one of the principal architects of the international order

established in 1815, set too much store by the international

‘system’ to intervene unilaterally against the wishes of the

other powers.

This aspect of the situation changed with the death of

Alexander and the accession by Nicholas I in December 1825.

The new tsar let it be known that if no agreement with the

other powers could be reached Russia would go it alone. This

threat eventually had its desired effect for, rather than see

Russia intervene on its own, first Britain agreed to autonomy

for Greece (in 1826) and then in June 1827 Britain, France and

Russia jointly decided to intervene to force a ceasefire on

the parties (thus in effect saving the rebels).

THE EARLY YEARS OF SULTAN MAHMUT II

37

When the sultan refused to accept the mediation of the

powers, their fleets first blockaded the Ottoman and Egyptian

navies in the harbour of Navarino on the western coast of the

Morea (Pelopponese), and then on 20 October destroyed them

completely, cutting off the Egyptian expeditionary force. This

effectively decided the conflict, but even though Mehmet Ali

agreed to withdraw his troops from the Balkans, the government

in Istanbul refused to face facts, which led to full-scale war

with Russia and disaster for the Ottoman army. At the Treaty

of Edime, concluded in September 1829, the Ottomans had to

recognize the independence of Greece and the autonomy of the

principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia and of a Serbia to

which several Ottoman districts were added. That the Greece

which emerged on the map was only a very small state, and fell

far short of the designs of the Greek nationalists, was only

due to the fact that Britain, France and Austria preferred a

malleable Ottoman Empire to a strong Greece dominated by

Russian influence.

Erik J, Zurcher. TURKEY: A Modern History

4- The Later Years of Sultan Mahmut II: the start of the

reforms

The Egyptian crisis

At the time of the Treaty of Edime the whole issue of Greek

independence was already starting to be overshadowed by what

developed into the most threatening crisis for the Ottoman

Empire in the first half of the nineteenth century, the

conflict between the sultan and his most powerful subject, the

governor of Egypt.

Mehmet Ali had come out of the Greek crisis with precious

little to show for his efforts and especially for the enormous

expense he had incurred. In 1827 he had lost his fleet into

the bargain. It is therefore understandable that he sought

recompense in other areas.

At first he tried to come to an agreement with the French

government. Traditionally, Egypt had close ties with France.

The French Catholic mission had been active in the country for

a long time, Napoleon’s occupation was still within living

memory, and French officers had played a leading role in the

building and training of Mehmet Ali s new army. Mehmet Ali

discussed with the French consul, Drovetti, an Egyptian

occupation of the North African Ottoman provinces

(Tripolitania, Tunisia and Algeria) with French support and

Ottoman acquiescence; in exchange the French would get

political and economic concessions in the area. Nothing came

of these plans. Instead France decided to occupy Algiers

herself.

Mehmet Ali now turned to Britain with similar proposals.

When Britain refused to co-operate, he decided to move alone.

He used a smouldering conflict with the Ottoman governor of

Acre over the latter’s refusal to return Egyptian peasants who

had fled Egypt as a pretext for a full-scale campaign to

conquer Syria in 1831. After

^

THE LATER YEARS OF SULTAN MAHMUT El

39

stubborn resistance by its governor, Acre fell in May 1832, In

July Mehmet Ali’s son Ibrahim Pasha, who commanded the

Egyptian army, twice defeated the Ottomans, completing the

occupation of Syria. The Ottoman government now officially

deposed Mehmet Ali and declared him a rebel. Mehmet Ali tried

to open negotiations, but when the government refused he

ordered his troops into Anatolia, where, on 27 December 1832,

they routed the Ottoman forces near Konya.

This disaster opened the road to the Ottoman capital for the

Egyptians. Mehmet Ali now temporized while he tried to reopen

negotiations. The Ottomans for their part desperately sought

foreign support against him. Britain refused to give anything

more than moral support. Austria’s Chancellor Mettemich was

equally inactive. In desperation the sultan now turned to his

traditional enemy, the Tsar, for help. The Russians, who saw

in Mehmet Ali a puppet of a French government (the July

monarchy of Louis Philippe) that they detested, also saw a

chance for a maior diplomatic victory and offered the sultan

diplomatic and military support.

When the negotiations between Mehmet Ali and the sultan

broke down again and Ibrahim Pasha’s forces started to march

on Istanbul, Russian troops landed on the Bosphorus on 5

April, 1833. They effectively forestalled any move of Ibrahim

Pasha against the capital, but they were not in a position or

in sufficient numbers to attack him. The sultan therefore had

no choice but to accept the substance of the demands made by

Mehmet Ali and to appoint him governor of Syria in May. In

addition his son, Ibrahim Pasha, was made tax-collector of the

district of Adana. The Russians received the diplomatic prize

they had aimed for in the shape of the treaty of Hiinkar

Iskelesi, concluded in July 1833, which basically was an

eight-year defensive alliance between Russia and the Ottoman

Empire.

The treaty made a deep impression in Britain, where

Russophobia had already been mounting, especially in liberal

circles. Now the cabinet, too, was deeply worried by the

threat of Russian penetration in the Middle East. Combating

the threat of Russian expansionism, as it was perceived in

London, became one of the main determinants of British foreign

policy for the next decades. At the same time, Britain became

deeply hostile to the man who had caused all this trouble,

Mehmet Ali,

Mahmut II never really accepted the loss of the Syrian

provinces and sought an opportunity to take revenge. In 1838

he sent his influential

Erik J. Ziircher. TURKEY: A Modern History

40

TURKEY: A MODERN HISTORY

Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mustafa Re$it Pasha, to London to

try to get the British government’s support for an attack on

Mehmet Ali. This support was not forthcoming, in spite of the

offer, and conclusion, of a free trade treaty which opened up

Ottoman markets (including, presumably, the areas to be

recaptured from the Egyptians) to British trade. Nevertheless,

in April 1839 the sultan felt strong enough to order an attack

on the Egyptian forces in northern Syria. The result was a

signal Ottoman defeat at Nizip on 24 June. To make matters

worse, shortly afterwards the Ottoman admiral in command of

the fleet in the Mediterranean, on hearing that one of his

arch-rivals had become grand vizier and that his fleet was

being recalled, sailed to Alexandria and handed over the

Ottoman fleet to the Egyptians.

The ‘Eastern Question’

The later years of Sultan Mahmut II saw a marked increase in

the major European powers’ interest in Ottoman Empire, The

Greek and Egyptian crises had shown up the empire’s weakness

and had alerted Britain to the strategic threat of the Ottoman

Empire coming within the Russian sphere of influence, which

would enable the Russians to threaten the British position in

the Mediterranean and in Asia. Austria, too, was increasingly

afraid of Russian domination in the Balkans. Imperial rivalry

between Great Britain and France was making itself felt again,

a generation after Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt.

The question of how to satisfy competing Balkan nationalisms

and the imperialist ambitions of the great powers without

causing the destruction of the Ottoman Empire, or, if this

destruction was inevitable (something of which the majority of

European statesmen were convinced), to dismember it without

upsetting the balance of power in Europe and causing a general

war, was known throughout the nineteenth century as the

‘Eastern Question’. It was high on the political and

diplomatic agenda in every European capital — and quite

righdy, too, for dissatisfied Serbian nationalism was to spark

off the First World War in 1914 and lead to the destruction of

not only the Ottoman but also the Austrian, Russian and German

empires.

The international political developments sketched here form

the background for the two, partly contradictory developments,

which set the pace in the Ottoman Empire from the late 1820s

onwards. On the one hand, the increasing incorporation of

parts of the economy into the capitalist world-system and its

attendant growth in trade

THE LATER YEARS OF SULTAN MAHMUT II

41

strengthened the position of those who profited from this

development, the Ottoman Christian traders, industrialists and

bankers. On the other, the government of Mahmut II, faced with

this process, under the personal direction of the sultan,

increased its efforts to strengthen the state through

military, administrative and fiscal reforms. Gradually,

military and political power and economic strength were

polarized between two distinct sectors of Ottoman society: the

predominandy Muslim military/bureaucratic elite and the

emerging Christian bourgeoisie.

The role of foreign powers in this context was ambivalent:

they, especially Britain from the 1830s to the 1870s,

encouraged modernizing reforms aimed at strengthening the

Ottoman state, but at the same time they jealously guarded

their commercial interests and the rights of their Christian

co-religionists, many of whom had become clients under the

berat-system. They pressed for equal rights for the sultan’s

Christian subjects as a touchstone for the sincerity of the

reforms, yet supported the Christian communities’ refusal to

give up their traditional rights under the millet system in

exchange for equality.

The sultan in control: the start of the reform movement

The policies of Sultan Mahmut II from 1826 onwards determined

the direction which Ottoman reform efforts would take for the

next 80 years. Like the policies of Selim III and those of his

great rival and inspiration, Mehmet Ali Pasha, they were

ultimately aimed at the strengthening of the central state

through the building of a modem army. All his reforms can be

understood as means to that end: building a new army cost

money, money had to be generated by more efficient taxation,

which in turn could only be achieved through a modem and

efficient central and provincial bureaucracy. Better

communications were needed to extend government control and

new types of education to produce the new-style military and

civil servants the sultan needed. Where Mahmut II went much

further than his predecessor (though not as far as Mehmet Ali)

was in his efforts to uproot the existing establishment,

abolishing or taming its institutions, and in the scope of his

reforms. Where Selim III had mainly tried to combat abuse of

the existing system, Mahmut created new administrative and

legal structures.

The turning point in the subjugation of the establishment was

the confrontation between Sultan Mahmut and the Janissaries in

1826.