Vulnerability of Aquaculture to Climate Change 7 SPC HOF meeting

advertisement

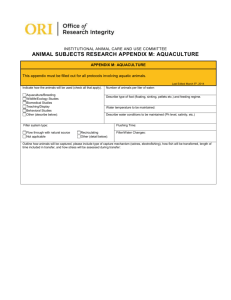

7th SPC HOF meeting Vulnerability of Aquaculture to Climate Change Tim Pickering SPC Inland Aquaculture Officer • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • One slide describing the main types of species examined Brief description of the surface climate and/or ocean variables used in your assessment to estimate the direct effects of climate change Projected changes to habitats that underpin the fishery used to show how indirect effects of climate change on stocks were assessed Examples of how projected changes to climate, ocean and habitats are expected to affect diversity and abundance of the key fish/invertebrate species Projected changes in production of fish/invertebrates in 2035 and 2100 under B1 and A2 in summary table (with confidence and likelihood ratings). Management recommendations (adaptations) Please present a summary table of relevant habitats and the expected percentage changes . Freshwater fisheries (Chapter 7) Aquaculture (Chapters 5,6,and 7) Coastal Fisheries (Chapters 5, 6 and 4) Oceanic fisheries (Chapter 4) In addition to the key adaptation measures needed to reduce threats to catches, and harness the opportunities, provided by climate change, please also include the main management measures needed for the habitats that support your fishery Outline • The main aquaculture commodities among PICTs • Climate variables most likely to affect aquaculture • How these variables could affect aquaculture species • Projected changes in production of aquaculture commodities in 2035 and 2100 under B1 and A2 scenarios • Management recommendations (adaptations) Aquaculture commodities supporting viable industries in PICTs • Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus • Freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii • Seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii • Blacklip pearl Pinctada margeritifera • Marine ornamentals (Coral, live-rock, clam, etc.) • Saltwater shrimp Penaeus monodon, Litopenaeus stylirostris Aquaculture commodities in research or small-scale commercial phases • Marine finfish, e.g Batfish Platax orbicularis, Rabbitfish Siganus lineatus, Milkfish Chanos chanos, Barramundi Lates calcarifer • Sea cucumber e.g. Sandfish Holothuria scabra • Giant clam, trochus, green snail for reef re-stocking • Others: mud crab Scylla serrata, Pacific oysters, Bush prawn Macrobrachium lar, Red-claw, Mabe pearl Projected changes to aquaculture environments • Aquaculture in PICTs uses all of terrestrial-freshwater, brackishwater, coastal and open-sea environments • The projected changes to these environments are the same as those described in the presentations today about Freshwater Fisheries, Coastal Fisheries, and Oceanic Fisheries Key climate variables that could affect aquaculture • • • • • • Temperature Rainfall (flooding, or drought) Cyclones Habitat alteration Sea-level rise Sea water acidification How these variables could affect aquaculture Fish kill in tilapia cage-culture, Vanuatu Temperature • Some aquaculture species (coral, seaweed) are already at the limit of their thermal tolerance • When corals get bleached by “warm-pool” events, Kappaphycus seaweed is also affected • Temperature and salinity stresses lead to “ice-ice”and Epiphytic Filamentous Algae (EFA) outbreaks Rainfall • Patterns of rainfall will change, leading to more rain in some places and more drought in others • In the tropical Pacific rainfall is expected to increase, improving the potential for freshwater aquaculture in much of Melanesia • Some areas may become more prone to flooding DFF (Fiji) Ltd Prawn Farm Cyclone Mick, December 2009 Cyclones • Cyclones may become more intense, but less frequent • Aquaculture infrastructure is put at risk by any cyclone, including structures and stock in coastal waters and installations like hatcheries on beach fronts Hunter Pearls hatchery, Fiji Islands Storm surge during Cyclone Tomas, February 2010 Habitat alteration • Warming and acidification are expected to progressively degrade coral reefs. Coral aquaculture depends upon mother colonies as sources of fragments for grow-out • Degradation of coral reefs or seagrass beds can reduce supply of giant clam or sea cucumber broodstock for hatcheries Sea level rise • Expected to cause major problems for the shrimp industry, because farming operations depend on the ability to drain ponds quickly and effectively. • Sea-level rise threatens the drainage of ponds, causes loss of quality because: (1) shrimp harvest is prolonged so stress is increased; (2) pond soil cannot be tilled and oxygenated between pond cycles Sea water acidification • Pearl oysters are likely to be badly affected by long-term declines in seawater pH • decreases in calcification reduce growth rates, lead to more fragile shells, and may also reduce pearl quality • All species that form bones or shells (finfish, shellfish, shrimp) could be affected Shell defect Some changes will be “positives” • Warmer temperature and increased rainfall is expected to benefit tilapia farming in Melanesia • Farming of Black Tiger Shrimp Penaeus monodon in New Caledonia may become practical • Milkfish fingerlings for capture-based culture will become available at higher latitudes Some impacts are indirect • Future price and availability of fish meal, a resource itself impacted by climate change, will affect the profitability of aquaculture that uses formulated pellet feeds (tilapia, prawn, shrimp, marine fin-fish) • Increase in water temperature will increase the prevalence of pathogens and fish disease in ways that are hard to predict Projected changes in production Aquaculture for food security • Tilapia, carp and milkfish aquaculture is expected to benefit strongly from the projected increases in temperature and rainfall, and to cope with other changes to the environment even though some of them are negative • These projected benefits are expected to be apparent by 2035, but well established by 2100, especially under the A2 emissions scenario • Farmable areas will expand to higher latitudes and altitudes Aquaculture for livelihoods • This should also apply in 2035 to freshwater prawns, however it may be reversed by 2100 due to the temperature tolerance of freshwater prawns and the effects of higher temperatures on stratification of ponds. • Most commodities dependent on coastal waters for hatchery production and/or grow-out are expected to incur losses of production, albeit at low vulnerability rating to 2035 • By 2100, the effects of climate change and ocean acidification on all livelihood commodities are negative and their vulnerability increases. • Under A2, seaweed farming and production of marine ornamentals are expected to have a high vulnerability, and the culture of pearls a medium vulnerability. • Shrimp farming, marine finfish farming and sea ranching/pond culture of sea cucumbers are likely to have a low-medium vulnerability • Vulnerability does not necessarily imply that there will be overall reductions in productivity of these commodities in the future. • Rather, it indicates that the efficiency of enterprises producing the commodity will be affected (because adaptation strategies will be needed) • Total production could still increase if the operations remain viable (albeit with reduced profit margins) and more enterprises are launched Pearl production • The ‘medium vunerability’ assessment may well need to be revised ‘downwards’, however, once the results of research on the effects of reduced aragonite saturation on the larvae and adults of pearl oysters, and on pearl quality, are examined in detail. • There is little scope for adaptive strategies, because pearl grow-out depends upon an opensea marine environment Shrimp production • Subject to adaptive strategies being adopted, the goal to double the production of the shrimp industry in New Caledonia to ~ 4000 tonnes per annum and 1000 livelihoods could still be met. B • Similarly, both Fiji and PNG should be able to retain their potential to produce 1000 and 2000 tonnes per year, respectively, employing about 500 people. Seaweed production • Continued selection of more suitable farming sites, farm methods, and seaweed varieties will be required to reduce vulnerability of seaweed culture. • Production targets of around 500 tonnes per year for both Fiji and Solomon Islands should still be achievable until 2035, but not necessarily in the same places or with the same industry management methods practiced currently Management recommendations Freshwater aquaculture • Promote the benefits of freshwater aquaculture, based on tilapia, carp and milkfish, in per-urban areas and for rural households, to supply fish to growing human populations that do not have good access to those coastal and freshwater fisheries resources likely to be enhanced by climate change, or to tuna at low cost. Shrimp • Identify which existing shrimp ponds can be modified by elevating the walls and floor to continue to function under rising sea levels, and which ones will need to be abandoned in favour of new ponds further landward at higher elevations. • Assess which alternative commodities may be able to be produced in those ponds that are no longer suitable for shrimp. • Intensify shrimp production, to better utilise the reduced area of flat coastal land (sea level rise) Cyclone-proofing, Pathogens • Assess designs of equipment and infrastructure for aquaculture and improve the resistance of these components to the effects of stronger cyclones. • Strengthen national capacity and regional networks to adopt and implement aquatic biosecurity measures, including capacity for monitoring, detection and reporting aquatic animal diseases, using international protocols (OIE 2010), to prevent introduction of new pathogens. Diversify the aquaculture sector • Maintain a watching brief on advances in aquaculture technologies in other regions to identify opportunities to diversify the sector in ways with potential to perform well under the changing climate (e.g. marine microalgae for biodiesel). • Consider transfer of such technologies, with the necessary biosecurity precautions, to increase the resilience of the sector. Fishmeal • Reduce dependence on fishmeal (tilapia, carp, milkfish, shrimp, freshwater prawns, marine finfish) by: (1) progressively replacing fishmeal with suitable local alternative sources of protein; and (2) promoting Best Management Practice (BMP) for feeding of farmed fish to increase feed efficiency. Carbon sinks • Promote aquaculture systems that are carbon sinks, like seaweed farming or pearls and edible molluscs. • Obtain official recognition of carbon capture by such systems and then target the seafood industry to purchase carbon offsets for such initiatives. • Pursue investment in carbon offset schemes that enhance the resilience of the coastal habitats on which aquaculture ultimately depends, such as mangrove planting and wetland conservation. Aquaculture statistics • A uniform system for collection of data on the volumes of production, value, number of farms, number and gender-balance of people employed, exports vs. domestic, etc., is essential not only for planning the development of the sector, but also for monitoring the effectiveness of adaptations to assist producers to optimise the opportunities presented by climate change, and minimize the adverse effects. May fish be with you!