Supplementary materials section: SM1: Scale-up:

advertisement

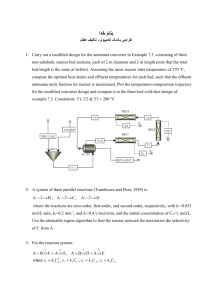

Supplementary materials section: SM1: Scale-up: Since cell damage due to elevated energy dissipation rate (turbulences, shear stress) is a basic issue in stirred tank reactors, scale-up of such reactor systems is generally performed by keeping constant either the energy input per unit volume (P = ρN3D5, where ρ = medium density, N = agitation rate, D = diameter of agitator) or the Reynold’s number across the reactor scale, in view of keeping constant the energy dissipation rate as well as the mean Kolmogorov length at the different reactor scales. That this is also valid for the scale-up of cell aggregate cultures of neural precursors could be shown by Gilbertson et al. 2006). In principle, stirring is rather simple at a spinner scale however, at a large scale the choice of the agitation system is highly critical. In view of large scale applications, Ibrahim & Nienow (2004) presented the hydrofoil HE3 impeller as optimal in order to minimise the mean specific energy dissipation rate for the suspension of microcarriers presenting thus a potential agitator for microcarrier cultures at a large (industrial) scale. However, presently, no information on the type and implementation of agitators for industrial scale microcarrier cultures is available in the open literature. Nevertheless, the largest reported process scale is a 6000L stirred tank reactor based microcarrier process for the production of influenza virus vaccine (Barret et al. 2009). In addition to classical engineering simulations, the implementation of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations provides a means for the verification of energy dissipation rate scalability at different scales of stirred tank reactors. Comparing different bioreactor configurations Johnson et al. (2014) could show that hydrodynamic scalability is achieved as long as design features, including baffles and impellers, remain consistent across the scales. In addition, it could be confirmed for single suspension cultures that the mean Kolmogorov length scale is considerably larger than the average cell size, signifying that substantial cell damage due to agitation is highly improbable. SM2: WAVE reactor (Fig. S1): A culture system characterized by the generation of less shear stress is the WAVE reactor (Singh 1999) which can be used for classical suspension and also for microcarrier dependent culture, but with a scale limit of 500L (working volume) due to oxygen transfer limitations beyond this scale. Using computational fluid dynamics, Öncül et al. (2009) have investigated flow conditions in 2L and 20L WAVE reactors. Under standard conditions using the non-dimensional Womersley number (Wo) and a parameter β according to Kurzweg et al. (1989), they could establish that the liquid flow in both bags was in a laminar state. Moreover, the maximum shear stress in the cellbags was around 0.01 N/m2 which is very low in comparison to stirred tank reactors where values exceeding 1 N/m2 can be observed (Joshi et al. 1996). For instance, Croughan & Wang (1991) reported a shear stress threshold of at least 0.7 N/m2 associated with damage of anchorage-dependent cells. Since turbulences and shear stress are much lower in this culture system it is well placed for medium scale cell propagation, in particular, of shear sensitive cells. In this context, Genzel et al. (2006) could show the beneficial effects of low turbulences and shear on cultivation of MDCK cells on microcarriers. In comparison to normal stirred tank bioreactors, higher cell densities on microcarriers were obtained. The WAVE reactor has also been shown to be of high interest for the expansion of human placental MSCs using microcarriers (Timmins et al. 2012). Moreover, microcarriers can be replaced by Fibra-cel chips in which adherent cells as well as those with a tendency to detach, like HEK293 cells, can be propagated but under considerably reduced shear fields in comparison to a microcarrier approach (Greene et al. 2012). Such an approach allows also the easy washing and medium exchange of immobilized cells which is more difficult for cells attached to traditional microcarriers. In addition to medium scale productions, WAVE type reactors are often used for the generation of biomass for the inoculation of large scale bioreactors. Packed bed/fixed bed reactor: A practical alternative for using microcarriers or macroporous carriers for the propagation of anchorage dependent cells but also of suspension cells is the use of packed bed reactors. However, from a large scale point of view this type of reactor system represents a medium scale production system because of scale limitations due the formation of nutritional and oxygen gradients across the fixed bed. In this type of bioreactors initially pioneered by Spier & Whiteside (1976) for the production of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus using BHK cells, the cells are attached to, immobilized on or entrapped in carriers: solid (Bliem et al. 1990) or macroporous carriers (Looby & Griffiths 1990), glass spheres, stainless steel gauze and coupons (Aboud et al. 1994), or porous spongelike materials, such as Fibra-cel (Kadouri & Zipori 1989). There are two types of fixed bed reactors: i) the fixed bed is separated from the conditioning vessel necessary for controlling pH and pO2 of the culture medium, like for the CellCube system (Fig. S2), or ii) the fixed bed and the conditioning vessel are integrated as for the Celligen packed bed reactor system (New Brunswick Scientific) (Fig. S3), or the Icellis system, more recently developed by ATMI. Both systems are characterized by the circulation of the culture medium through the fixed bed reactor as shown in Fig. S3. The main advantage is that under controlled conditions (pH, pO2, medium circulation) tissue like cell mass can be achieved (up to 2x108 c/ml carrier) allowing a significant improvement of reactor productivity and thus a considerable intensification of cell culture process. In this context, in view of the production of monoclonal antibodies using hybridomas, Bliem et al. (1990) reported that a fixed bed reactor of a bed volume of 21 L can produce 200-300 L of culture supernatant per day which is comparable to a 1500 L stirred tank reactor. Further advantages relate to the use of shear sensitive cells or biological production systems. The production of retroviral vectors (MLV-based) using various anchorage dependent cell lines (ψCRIP, PG13, TeFLY) was only possible using packed bed reactors due to reduced shear stress which negatively impacted cell specific production rate in the case of microcarrier based cultivation. 0.5 – 1.5 log differences in reactor productivity in favour of fixed bed reactor have been observed (Merten 2004). Moreover, using human diploid fibroblast cultures, only fixed bed reactors could be used for the production of hepatitis A virus for vaccine purposes due to heterogeneous cell distribution and aggregation for microcarrier cultures when cultures got confluent as well as during the virus production phase (Aunins et al. 1997, Junker et al. 1992). For the same reason, the ‘large-scale’ CellFactory system (CF-40 system) had been initially implemented for the production fibroblast interferon (Pakos & Johansson 1985) (see 4.1.). As for the production of various biologicals, packed bed reactors are also of interest for the expansion of stem cells for different purposes. SM3: Hollow fibre reactor: Hollow fibre reactors, initially developed by Knazek et al. in 1972, are culture systems allowing the production of tissue like cell concentrations (>108 c/ml). They are characterized by a separation of the cell culture chamber (which is outside the hollow fibres) and a medium compartment (inside the hollow fibres). In order to feed the cells with nutrients and oxygen and to remove metabolic waste, the medium is circulated from a conditioning vessel to the cartridge, passes through the fibres and circulates back to the conditioning vessel which allows the control of pH and pO2 as well as a continuous or discontinuous medium exchange (- perfusion culture)(fig. S4). This perfusion allows the exchange of nutrients and waste across the hollow fibre membranes according to the chosen cut-off. Further advantages are reductions in required materials such as serum, growth factors or other additives. The main drawbacks are the limited scalability, formation of nutrient gradients as well as the difficulties to harvest cells because initially, these devices have not been developed for the expansion of stem cells but for the production of secreted proteins. A particular system based on an interwoven four compartment capillary membrane technology for 3D perfusion with decentralized mass exchange had been used for the expansion of hESCs (Gerlach et al. 2010) and liver stem cells (Monga et al. 2005). Rotating-wall perfused reactors: A second system of particular interest for the expansion of clump and aggregate cultures (such as embryoid bodies (EBs)) or cells grown on carriers or scaffolds (Martin & Vermette 2005) represents the rotating-wall perfused reactors from Synthecon-EHSI (Fig. S5). Both reactor systems have been developed for use in space. They are characterized by a very soft agitation and indirect oxygenation via a gas exchange membrane. This membrane is either localized in the centre of the culture vessel as for the STLV (Fig. S5A) or localized laterally on one side as for the HARV (Fig. S5B). The membrane area to culture volume ratio is larger for the HARV allowing a reduction in the rotation speed. Whereas in space, both devices can be run under micro-gravity regime, this is less sure for using under ‘Earth’ conditions. These differences have an impact on the shear level. For instance a 2 mm cancer-cell aggregate sees its Reynold’s number passing from 0.19 in space to 86 on Earth corresponding to an increase of the shear level from 0.0002 to 0.11 N/m2 (Martin & Vermette 2005). Although both devices are of interest for the cultivation of various cells under very low shear fields and have shown their interest for the culture of cancer-cell aggregates (Martin & Vermette 2005), hESCs/EBs (Zhao et al. 2006, Côme et al. 2008), MSCs (Chen et al. 2006) and hematopoietic stem cells (Liu et al. 2006), these culture systems are not destined for large scale expansion of any cell type. Moreover, due the very low shear fields, there is limited control of the aggregate size leading to the formation of necrotic centres due to cell death inside the aggregates. SM4: Mechanosensitivity of stem cells – some background information: MSCs: Mechanical stimuli (including fluid shear stress) are detected via ion channels and integrins (both considered as mechanoreceptors involved in mechanotransduction for activating downstream ERK1/2), glycocalyx (considered as primary sensor for mechanical stimuli triggering two distinct cellular signalling pathways) and cytoskeleton (via actin organization regulating cell stiffness, itself influenced by the substrate stiffness). For instance, MSCs grown on stiff substrates spread out leading to cytoskeletal contraction generating high level of tensile forces pulling on the surface (Patwari & Lee 2008). This promotes differentiation towards the osteoblast lineage. In this context, Arnsdorf et al. (2009a) demonstrated in mouse MSCs that the small GTPase RhoA and its effector protein ROCKII regulate fluid flow induced osteogenic differentiation, and that the activation of RhoA and actin tension are negative regulators of adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation. Specifically, non-canonical Wnt5a signalling involving Ror2 and RhoA as well as N-cadherin mediated β-catenin signalling are required for mechanically induced osteogenic differentiation (Arnsdorf et al. 2009b). Moreover, Dupont et al. (2011) could establish by comparing two different elastic moduli (0.7 and 40 kPa) that stiffness is sensed via the modulation of YAP/TAZ activity. Osteogenic differentiation is induced on stiff ECM when YAP/TAZ are active, whereas depletion of YAP/TAZ is related to adipogenic differentiation normally induced on soft ECM. The knockdown of YAP/TAZ enabled adipogenic differentiation on stiff substances, thus mimicking a soft environment. Thus, a stiff culture surface (increased matrix stiffness (11-30 kPa)) together with an adapted biochemical matrix such as polyallylamine promotes spindle-like shape and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs (Huebsch et al. 2010); a matrix with E=2.5-5 kPa leads predominantly to adipogenic differentiation, whereas soft matrix (E<1 kPa) leads to neural differentiation (Engler et al. 2006, Lanniel et al. 2011, Shih et al. 2011). Finally, Doroudian et al. (2013) could show that applied mechanical stresses tend to dominate over the scaffolds properties. The reviews by Liu et al. (75) as well as Sart et al. (58) provide details on the mechanisms of osteogenic differentiation of human MSCs and the impact of biomechanical stem cell fates on MSC differentiation. PSCs: As for MSCs, PSCs are able to sense matrix mechanics. Zoldan et al. (2011) demonstrated that hESCs grown on hard surfaces promoted mesodermal commitment, surfaces with intermediate elastic modulus promoted endodermal differentiation and soft surfaces led to ectodermal differentiation. In addition, the self-renewal of hESCs was promoted by hard surfaces (>6 MPa) which is in contrast to mouse ESCs. Chowdhury et al. (2010) reported that mESCs could maintain their pluripotency under long-term conditions (>15 passages) when cultured on soft polyacrylamide gels (E~500Pa), whereas hard substrates favoured differentiation towards mesodermal and endodermal lineages. Finally it is important to consider that the local microenvironment of aggregates is impacted by the size of the aggregates. It modulates endogenous parameters influencing thus the differentiation trajectories of PSCs (Bauwens et al. 2008). In this specific context, the choice of the culture system whose fluid shear forces have a direct impact to aggregate size is highly critical and agitation has to be carefully optimized for obtaining and maintaining the optimal aggregate size also in order to direct differentiation into the desired direction. More information on the effect of biomechanics on stem cell fate can be found in the review by Sun et al. (2012). References: Aboud RA, Aunins JG, Buckland BB, Hagen A, Hennessey J, Junker B, Lewis J, Oliver C, Orella C, Sitrin R (1994) Hepatitis A virus vaccine. Patent Application WO 94/03589, published February 17, 1994. Arnsdorf EJ, Tummala P, Kwon RY, Jacobs CR (2009a) Mechanically induced osteogenic differentiation – the role of RhoA, ROCKII and cytoskeletal dynamics. J Cell Sci 122, 546-553. Arnsdorf EJ, Tummala P, Jacobs CR (2009b) Non-canonical Wnt signaling and N-cadherin related beta-catenin signaling play a role in mechanically induced osteogenic cell fate. PLoS One 4, e5388. Aunins JG, Bibila TA, Gatchalian S, Hunt GR, Junker BH, Lewis JA, Licari P, Ramasubramanyan K, Ranucci CS, Seamans TC, et al. (1997) Reactor development for the hepatitis A vaccine VAQTA. In: Animal Cell Technology. From Vaccines to Genetic Medicins (eds. Carrondo MJT, Griffiths B, Moreira JLP), pp. 175-183, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht/NL. Barrett PN, Mundt W, Kistner O, Howard MK (2009) Vero cell platform in vaccine production: moving towards cell culture-based viral vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines 8, 607-618. Bliem R, Oakley R, Matsuoka K, Varecka R, Taiariol V (1990) Antibody production in packed bed reactors using serum-free and protein-free medium. Cytotechnology 4, 279-283. Bauwens CL, Peerani R, Niebruegge S, Woodhouse KA, Kumacheva E, Husain M, Zandstra PW (2008) Control of human embryonic stem cell colony and aggregate size heterogeneity influences differentiation trajectories. Stem Cells 26, 2300-2310. Chen X, Xu H, Wan C, McCaigue M, Li G (2006) Bioreactor expansion of human adult bone marrowderived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 24, 2052-2059. Chowdhury F, Na S, Li D, Poh YC, Tanaka TS, Wang F, Wang N (2010) Material properties of the cell dictate stress-induced spreading and differentiation in embryonic stem cells. Nat Mater 9, 82-88. Côme J, Nissan X, Aubry L, Tournois J, Girard M, Perrier AL, Peschanski M, Cailleret M (2008) Improvement of culture conditions of human embryoid bodies using a controlled perfused and dialyzed bioreactor system. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 14, 289-298. Croughan MS, Wang DI (1991) Hydrodynamic effects on animal cells in microcarrier bioreactors. Biotechnology 17, 213-249. Doroudian G, Curtis MW, Gang A, Russell B (2013) Cyclic strain dominates over microtopography in regulating cytoskeletal and focal adhesion remodeling of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430, 1040-1046. Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, et al. (2011) Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179-183. Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE (2006) Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677-689. Genzel Y, Olmer RM, Schäfer B, Reichl U (2006) Wave microcarrier cultivation of MDCK cells for influenza virus production in serum containing and serum-free media. Vaccine 24, 6074-6087. Gerlach JC, Lübberstedt M, Edsbagge J, Ring A, Hout M, Baun M, Rossberg I, Knöspel F, Peters G, Eckert K, et al. (2010) Interwoven four-compartment capillary membrane technology for threedimensional perfusion with decentralized mass exchange to scale up embryonic stem cell culture. Cells Tissues Organs 192, 39-49. Gilbertson JA, Sen A, Behie LA, Kallos MS (2006) Scaled-up production of mammalian neural precursor cell aggregates in computer-controlled suspension bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng 94, 783792. Greene MR, Lockey T, Mehta PK, Kim YS, Eldridge PW, Gray JT, Sorrentino BP (2012) Transduction of human CD34+ repopulating cells with a self-inactivating lentiviral vector for SCIDX1 produced at clinical scale by a stable cell line. Hum Gene Ther Methods 23, 297-308. Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, Rivera-Feliciano J, Mooney DJ (2010) Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nat Mater 9, 518-526. Ibrahim S, Nienow AW (2004) The suspension of microcarriers for cell culture with axial flow impellers. Chem Eng Res Des (Trans I Chem E, Part A) 82, 1082–1088. Johnson C, Nataraja V, Antoniou C (2014) Verification of energy dissipation rate scalability in pilot and production scale bioreactors using computational fluid dynamics. Biotechnol Prog 30, 760-764. Joshi JB, Elias CB, Patole MS (1996) Role of hydrodynamic shear in the cultivation of animal, plant and microbial cells. Chem Eng J Biochem Eng J 62, 121-141. Junker BH, Wu F, Wang S, Waterbury J, Hunt G, Hennessey J, Aunins J, Lewis J, Silberklang M, Buckland BC (1992) Evaluation of a microcarrier process for large-scale cultivation of attenuated hepatitis A. Cytotechnology 9, 173-187. Kadouri A, Zipori D (1989) Production of anti-leukemic factor from stroma cells in a stationary bed reactor on a new cell support. In: Advances in Animal Cell Biology and Technology for Bioprocesses (eds. Spier RE, Griffiths JB), pp. 327-332, Butterworths, Sevenoaks/U.K. Knazek RA, Gullino PM, Kohler PO, Dedrick RL (1972) Cell culture on artificial capillaries: an approach to tissue growth in vitro. Science 178, 65-66. Kurzweg UH, Lindgren ER, Lothrop B (1989) Onset of turbulences in oscillating flow at low Womersley number. Phys Fluids A: Fluid Dynam 1, 1972-1975. Lanniel M, Huq E, Allen S, Buttery L, Williams PM, Alexander MR (2011) Substrate induced differentiation of human mesenchymal on hydrogels with modified surface chemistry and controlled modulus. Soft Matter 7, 6501-6514. Liu Y, Liu T, Fan X, Ma X, Cui Z (2006) Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood in rotating wall vessel. J Biotechnol 124, 592–601. Liu L, Yuan W, Wang J (2010) Mechanisms for osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells induced by fluid shear stress. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 9, 659-670. Looby D, Griffiths JB (1988) Fixed bed porous glass sphere (porosphere) bioreactors for animal cells. Cytotechnology 1, 339-346. Martin Y, Vermette P (2005) Bioreactors for tissue mass culture: design, characterization, and recent advances. Biomaterials 26, 7481-7503. Merten O-W (2004) State-of-the-art of the production of retroviral vectors. J Gene Med 6, S105-S124. Monga, SP, Hout MS, Baun MJ, Micsenyi A, Muller P, Tummalapalli L, Ranade AR, Luo JH, Strom SC, Gerlach JC (2005) Mouse fetal liver cells in artificial capillary beds in three-dimensional fourcompartment bioreactors. Am J Pathol 167, 1279–1292. Öncül AA, Kalmbach A, Genzel Y, Reichl U, Thévenin D (2009) Characterization of flow conditions in 2 L and 20 L Wave bioreactors® using computational fluid dynamics. Biotechnol Prog 26, 101-110. Pakos V, Johansson A (1985) Large scale production of human fibroblast interferon in multitray battery systems. Dev Biol Stand 60, 317-320. Patwari P, Lee RT (2008) Mechanical control of tissue morphogenesis. Circ Res 103, 234-243. Sart S, Agathos SN, Li Y (2013) Engineering stem cell fate with biochemical and biomechanical properties of microcarriers. Biotechnol. Prog. 29, 1354-1366. Shih YR, Tseng KF, Lai HY, Lin CH, Lee OK (2011) Matrix stiffness regulation of integrin-mediated mechanotransduction during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res 26, 730-738. Singh V (1999) Disposable bioreactor for cell culture using wave-induced agitation. Cytotechnology 30, 149-158. Spier RE, Whiteside JP (1976) The production of foot-and-mouth disease virus from BHK 21 C 13 cells grown on the surface of glass spheres. Biotechnol Bioeng 18, 649-657. Sun Y, Chen CS, Fu J (2012) Forcing stem cells to behave: a biophysical perspective of the cellular microenvironment. Annu Rev Biophys 41, 519-542. Timmins NE, Kiel M, Günther M, Heazleewood C, Doran MR, Brooke G, Atkinson K (2012) Closed system isolation and scalable expansion of human placental mesenchyma stem cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 109, 1817-1826. Zhao ELL, Guo YS, Wang XM, Jiand CY, Li H, Duan J, Song YCM (2006) Enrichment of cardiomyocytes derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. J Heart Lung Transplant 25, 664-674. Zoldan J, Karagiannis ED, Lee CY, Anderson DG, Langer R, Levenberg S (2011) The influence of scaffold elasticity on germ layer specification of human embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 32, 96129621. Supplementary figures: Figure S1. WAVE reactor design (Singh (1999), reproduced with permission). Figure S2. CellCube, lab version (module 25) (Corning). Figure S3. Celligen – packed bed reactor perfusion system (New Brunswick Scientific). Level control Fresh medium Waste, harvest Base Figure S4. Flow diagramme of a hollow fibre reactor system (placed inside an incubator at 37°C). NNNNN Figure S5. Rotating-wall perfusion reactor. A. Slow turning lateral vessel (STLV) reactor. B. High aspect ratio vessel (HARV) reactor (Martin & Vermette (2005), reproduced with permission). A) B)