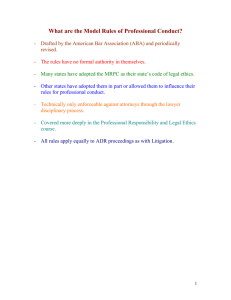

COMPARATIVE ETHICS Allen Spring, 2004

advertisement