PROPERTY OUTLINE - BECKER

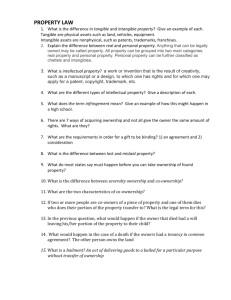

advertisement