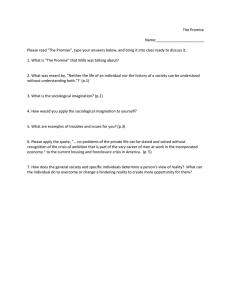

How promises become enforceable 1. Mutual Assent Objective Assent

advertisement