Document 15964551

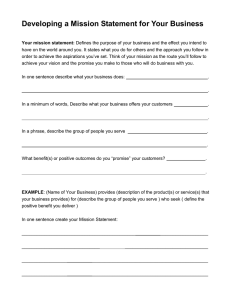

advertisement