WORKSHOP: ISSUES FOR THE FAMILY COURT. HOW

advertisement

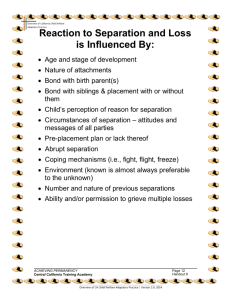

WORKSHOP: ISSUES FOR THE FAMILY COURT. HOW CAN RESEARCH INFORM PRACTICE? “Try to take into account the kids’ views because the kids know what they want more than the parents do because they’re them.” I. OUTCOMES FOR CHILDREN On average children who experience divorce are between one and a half to two times as likely to experience adversity as those whose parents do not separate [Amato, 1991 #129; Amato, 1993 #6; Amato, 2000 #829; Pryor, in press #985; Simons, 1996 #710]. However, the majority of children whose parents separate do not suffer negative outcomes in the medium to long-term. Separation is a process that starts sometimes years before one parent leaves the home, and continues on afterward. Separation in itself explains little of the variance in outcomes for children. Evidence for this includes: Adverse outcomes are higher in children before separation, whose parents subsequently divorce [Cherlin, 1991 #74; Elliott, 1991 #67] Those whose parents ‘stay together for the sake of the children’ are also at risk for adverse outcomes when their parents later separate [Furstenberg, in press #949; Kiernan, 1992 #51; Pryor, 1999 #616] If loss of a parent from the home was a major explanatory factor, then children who lose a parent by death should be equally at risk. They are not [Rodgers, 1998 #362]. Factors that explain variation in outcomes for children include: Conflict before, during, and after separation The psychological well-being of the custodial parent Household income Quality of relationship with non-resident parent Child-based factors such as appraisals, understandings, temperament, locus of control Community and extended family support and stability AND, most important, the quality of parenting and the parent-child relationship. II. CHILDREN’S PERSPECTIVES ON FAMILIES AND FAMILY TRANSITIONS Children are usually distressed and sad when their parents separate. HOWEVER, it is not always a negative experience. In Ann Smith’s study 44% reported neutral or positive reactions [Pritchard, 1998 #622; Walczak, 1984 #19]. Young children may blame themselves, and long for reconciliation sometime after the separation [Kurdek, 1980 #571]. Children are not often told about what is happening, either before or after the event. (5% in UK study felt they had a full explanation; a half of Anne Smiths’ group still did not know why their parents had separated two years later). If they do receive good information and explanation, then they cope better later in life [Gollop, 2000 #1046; Gollop, 2000 #939; Smith, 1997 #698]. Children most often cite the loss of day-to-day contact with their non-resident parent as the worst aspect of the separation. Children are rarely consulted about living arrangements made for them by adults. In one UK study, about 30% wanted adults to decide, another 30% wanted to decide themselves, and the rest wanted to participate in decision-making without being totally self-determining [Brannen, 1999 #826; Smart, 1999 #558]. When asked about living arrangements in principle, children are most likely to say that equal time with both parents is optimal. These opinions vary little according to the family structure young people themselves live in, the gender and age of children, and the presence or absence of conflict. Almost no children or young people endorse not seeing both parents at least some of the time [Derevensky, 1997 #418; Kurdek, 1986 #653; Pryor, 2001 #654]. The people to whom children most often turn for support and advice at the time of separation are extended family members, especially grandparents, and to friends. They rarely use counsellors, and find parents too absorbed in their own problems to be approachable. Are children’s views associated with outcomes? We do not know whether levels of distress at the time of separation is linked with long-term outcomes Good communication between parents and children at the time of separation has been found to be linked to better adaptation in later life [Mitchell, 1985 #44] Knowing why a separation is happening and receiving adequate explanations allows children to attribute its happening to known causes. Attribution to unknown causes has been found to be linked with anxiety, depression and conduct disorder [Kim, 1997 #868] Even when there is no contact with fathers, it has been found that knowledge about absent parents is linked with well-being [Owusu-Bempah, 1995 #38] Frequency and regularity of contact with fathers do not by itself predict outcomes; closeness and quality of parenting do [Amato, 1999 #455] We have little evidence about the benefits of having a say in living arrangements. One study has found that input into decision-making was associated with positive feelings about the arrangement [Dunn, in press #971]. Evidence for the benefits of one living arrangement is mixed; it is probable that in itself it is not as important as other factors. We have little evidence on the importance of support from extended family members. One study has found that closeness to maternal grandmothers was linked to children’s adjustment [Lussier, submitted #988] Children’s perspectives on families Children view families in diverse and idiosyncratic ways that may bear little resemblance to the standard notion of a family The most common criterion used at all ages for defining a family is the presence of love Young children tend to use notions of co-residence, the presence of two parents, the presence of children, and blood relations as definitional of families [Fu, 1986 #1062; Funder, 1996 #445; Gilby, 1982 #649; O'Brien, 1996 #892] In a New Zealand study, over 80% of adolescents endorsed the following as ‘family’: married parents and children; cohabiting parents and children; lone mothers and fathers with children; grandparents, aunts and uncles [Anyan, 1998 #784] Although children tend to hold ‘conservative’ views of families, they are adaptive and resilient in the face of family change so long as they are supported in appropriate ways PATERNAL INVOLVEMENT IN FAMILIES BEFORE AND AFTER SEPARATION Fathers in intact families On average, fathers spend 44% of the time mothers do engaged with children They spend 66% of the time mothers do being available to children Fathers are still less likely to be responsible for children in areas such as organizing childcare, being available for sick children, etc. The nature of the father-child relationship is more important for children’s well-being than the amount of contact. Nurturing, monitoring and support are vital components of fathering (and parenting in general) [Amato, 1998 #345; Amato, 1999 #599] Fathers after separation Involvement before separation is not necessarily a good predictor of involvement after separation. Predivorce division of responsibilities between parents represented different types rather than different degrees of commitment to children’s welfare Father-child contact after separation typically falls off over time. Fathers are more likely to stay in contact with boys than with girls A curvilinear relationship between frequency of contact and distress in young adulthood [Laumann-Billings, 2000 #825] What predicts father-child contact? Relationship between parents Geography Child support Child’s age Judicial system Does father-child contact matter for children? Contact, from a child’s perspective, is usually a good outcome in its own right Frequency and regularity by themselves do not link with positive outcomes Feelings of closeness are positively linked with psychological well-being and academic success, and negatively with anxiety Authoritative parenting (warmth, monitoring, support) is positively and strongly associated with child and adolescent well-being after divorce III. CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE Conflict Parental conflict in intact and divorced families has well-documented effects on children [Cummings, 1994 #401; Davies, 1998 #500; Grych, 1990 #160; Grych, 1998 #499; Harold, 1997 #265; Harold, 1997 #347] The evidence is clear that children whose parents maintain high levels of conflict are better off in measurable ways if their parents separate [Amato, 1997 #389; Jekielek, 1998 #346; Morrison, 1999 #712] There is some evidence that children whose parents who exhibit low levels of conflict before they separate are worse off after separation. This may reflect the fact that children fail to see the separation coming, or that ‘emotional divorce’ (withdrawal, contempt) may be at least as damaging [Booth, 2001 #830; Booth, 1999 #893; Hetherington, 1999 #853] An important factor in considering the impact of conflict is the way in which it is appraised by children and adolescents Domestic Violence There is a major dilemma between the right of children to be protected from the risk of psychological harm, and their right to have their relationships with both parents fostered [Smith, 1999 #936]. Children vary in their own views. Some want no contact with parents who have been violent to the other; others want to see their parent [Chetwin, 1998 #937] It might be useful to distinguish between control-initiated and conflict-initiated violence [Ellis, 1996 #984; Johnston, 1999 #934; Johnston, 1993 #104] Psychological assessments of parents are important Children who have no contact with an abusive parent tend either to idealise or to demonise that parent [Gorrell Barnes, 1998 #628] Children’s own feelings need to be taken into consideration Considerations from attachment By the age of 18 months children have normally formed multiple attachments Two kinds of behaviour that are almost universal are stranger anxiety and separation anxiety. These are manifested by distress. When children lose an attachment figure they demonstrate a cycle of protest, anger, and despair. This may be repeatedly initiated if contact is infrequent As children get older they can maintain relationships by other forms of contact such as phone, e-mail, letters, etc. IV. IMPLICATIONS FOR LIVING ARRANGEMENTS Some major points to consider when making decisions about living arrangements Parent-child relationships, both past, present, and future Children’s views, feelings, and wishes Parenting skills of parents, both actual and potential Ages of children Psychological well-being of parents Parents’ individual abilities to put needs of children first and to recognise and respect the children’s needs for good relationships with both parents Parents’ abilities to contain and reduce conflict Michael Lamb’s five implications: I. II. III. IV. V. V. Determine whether relations between noncustodial parents are worthy of support and protection Determine whether conflict is sufficiently intense and likely to continue indefinitely Ensure that contact with the non-residential parent includes a broad range of everyday activities including chores and monitoring Ensure that plans include details of transitions and detailed blocks of time, and that they allow for changes as children’s developmental needs change Do not misinterpret failures to compromise as symptoms of underlying conflict too intense to permit co-parenting. Custody awards should promote children’s best interests, not reward or punish parents for real or alleged histories of involvement. CONCLUSIONS Children need clear, age-appropriate explanations about what is happening and why Children need support, from extended family and parents where possible Quality relationships with both parents should be fostered, unless there are compelling reasons why not Parents need support for authoritative parenting, through information and education Include children in the decision-making process as appropriate to their age and willingness to be involved. As a minimum, hear their views