Malnutrition is a matter of political economy! Sachin Kumar Jain

advertisement

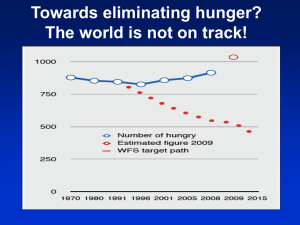

Malnutrition is a matter of political economy! Sachin Kumar Jain “When people go hungry, it’s not simply the food that is in short supply, it’s JUSTICE!” -From unknown reference Can you enjoy song and dance, if you are empty stomach? Can you walk towards a holy place for prayers, if you are hungry? You are provided with best playgrounds and schools; will your child be able to utilize those infrastructures, if she has not eaten food for few days? Can you survive, if you are fed with cereals alone every day? Do you think, you would like to do swimming in the swimming pool, if are fed with the food, which fulfils half of your requirements regularly? In such a situation, would you decide to for purchasing mobile phone or iPod? Your response to these questions is the response to the title of this article. Let me refer to about a recent visit the Vikas Samvad made to a village in Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh. I am from Madhya Pradesh, a state that lies at the heart of India – madhya means 'central' in Hindi – and Sheopur is an adivasi majority district - the adivasis are India’s indigenous tribal communities. The Sahariya community lives in Kakra village. The village is under Pohri Development Block. The village stretches eight kilometres along the roadside from the block headquarters. When we entered the village we saw many children cracking nuts of a berry-like fruit to retrieve its kernel to eat it. I sat beside the children by the side of the road, and joined them in breaking the nuts to get at the kernels. Then I asked one of the children what this fruit was? The boy pointed to a nearby mound of cattle dung and innocently told me the village cattle ate the fruit while grazing in the forest and excreted the nut along with their dung. I was taken aback. I am sure that most of you would also have reacted similarly. We then visited some houses in the village. All of them presented a similar picture. Pot-bellied infants in the lap of their mothers or grandmothers, peering at us through matter-encrusted eyes, munching dry roti –ie., the unleavened, homemade wheat bread that is the main stay of the Indian diet. Almost every home had about 20 kg of wheat - which is what each family gets every month through the government’s public distribution system. There was no sign of any other food grain … absolutely nothing. Upon inquiry we found that no house had pulses to be cooked for the past 20 days. Violation of Right to Food A vicious circle of: dispossession from land, livelihood and resources- > hunger, starvation, malnutrition >> stunting > > > even more dispossession and exclusion. Creates chronic hunger leading to malnutrition, exclusion & deprivation!! Hunger affects children the most and kills them FIRST The concept of nutrition was absent in this village, and none could afford it. Seeking drinking water, the villagers must cross the road, walk over half a kilometer downhill, to reach the two hand-pumps installed by the government. That was their only source of water and there is no water storage facilities provided in the village. If you think this village is an exception, let me tell you I have visited scores of similar villages in the state. In fact, if you make photocopies of your mental image of Kakra you could paste them across large swathes of India. Malnutrition is linked to food insecurity and children are its prime victims In 2001, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), a civil society group, filed public-interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court of India questioning the role of the state in ensuring food security for the people and to prevent starvation deaths. The PIL took the cloak off a bitter truth – that starvation was an integral part of children's lives, widowed women, the aged, the differently abled, indigenous tribes and caste groups that faced social discrimination. Malnutrition is a national crisis today and the condition is endemic in India. Children are the most susceptible victims. A staggering 65 million children aged below five years – 42 percent of the country’s population in that age group – are inescapably trapped in its web. Of the estimated 1.47 million children in this age group who die every year (given the child mortality rate of 64 per 1,000 live-births), malnutrition is a prime cause of death in 1.1 million cases. One in every two child is under-nourished, a third of the children who die every year across the world are Indian, and 8 out of every 15 women of child-bearing age are anemic. The Indian government conducts a National Family Health Survey every seven years to collate information on social and other factors influencing the health and nutritional status of the people. According to its third survey (2005-06), 42.5 percent of the child population is underweight, 48 percent is stunted, and only 24.5 percent was breastfed within an hour of birth. The situation is even more dismal in the adivasi and dalit population – dalits are the most socially discriminated against castes in India’s caste system. Growth is stunted in 53.9 percent of children while 54.5 percent of adivasi children and 47.9 percent of dalit children are underweight for their age. Figure 1 If Malnutrition is the base for drawing boundaries of country's political MAP; It is the new world! The Indian Context World’s second fastest growing economy at 6% to 8% growth rate; Produces 235 million tonnes of food grain annually of which 78% is wheat and rice alone; less space for other nutritious millets; Public Distribution System (PDS) and ICDS, world’s largest food subsidy programme. Procures 85 Million tonnes food grains directly from the farmers for PDS, buffer and price stabilisation. Yet, for 63% population that depends on agriculture situations are bad. 253000 farmers committed suicide (1995-2012) due to distress & debt. Millions of tonnes of food grain rot annually, improper storage and maintenance and hence do not reach the poor. 10 central food, employment, social security programs (Direct Food Support, Employment to Earn food and cash assistance. Protein and energy deficiency, yet policies focus on cereals & mono-cropping. 42.5% children malnourished, more than 50% women anemic, 77% population surviving on less then US 40 cents (Rs 20) per day and 80% not getting prescribed level of energy (calories), 1.4 million child deaths every year. Results are catastrophic. 65 million children are malnourished and a whopping 60 million stunted. Malnutrition matters in India High calorie gap among children ranging from 550 to 1000 calorie against ICMR standards of 1250 calories for children at the age of 1 & 1650 calories for those below 5, causing irreversible damages; Budget allocation less than 1% for children under 6, but writes off US 537 billion in 6 years as corporate tax exemptions and reliefs; Businesses then opposes government welfare schemes for the poor; Governments cites lack of funds as the primary reason for rejecting demands like universalisation of ICDS; Government promotes a targeted approach for key social welfare schemes and remains non-committal on nutritional Security in the National Food Security Bill 2011. Perspectives on childhood hunger Womb to grave: Malnourished mothers – condition deteriorates during infant/young feeding, most perish; Causes disability; The families caught in the web of displacement and distress migration complicate the situation; Diseases; lack of access to primary health services; sanitation; Contrasts state obligation to protect rights and guarantee health; Nutrition programme focuses on delivering cereals occasionally (as calories should come from varied sources ranging from fats to fruits), lacking universal coverage and adequate resource allocation (US $ 0.12 per day per children); Institution and market-based approach to deal with micronutrient fortification and medicalisation of Food ; Why? Governance by consultation has stopped; NFSB 2011; Only English language version of the Bill was available on WEBSITE; for a period of 25 days; no discussion out of the Parliament; advertisement published in 12 newspapers; 9 were English; when a people’s organisation takes this to the people; defined as threat to the State; Annual budget is consulted with corporate entities not with farmers; even no scope for MPs; Five-year plans made by Planning Commission, decides how 35% of India’s budget to be spent; without any discussion in the Parliament; Public opinion should find respect or not?? GDP Vs Hunger Growth-based development concept does not decline malnutrition; GDP Growth rates (2001-2010) – 5% to 8.5% Malnutrition declined – 0.1% per year or 1% decline in 10 Years Nutritional poverty – increased from 64% to 80% Increasing divide between RICH and POOR; where RICH are being treated with EQUITY in GROWTH, whereas POOR are treated with most MINIMUM WAGES. The Buffer Stock Buffer stock of food grains ~31 million tonnes to deal with emergency, to keep market prices stable and to feed people in different conditions. The food grain is procured from farmers on MSP in crop seasons every 6 months; BUT State has stocks of 85 million tonnes of food grain; if you pile-up food-grain bags one above the other, it can reach the moon -thrice; It is rotting, Supreme Court asserted that state cannot let people die of hunger amidst this rotting of food and directed it to distribute it among the people but PM said don’t interfere in policy matters. Malnutrition matters in India High calorie gap among children ranging from 550 to 1000 calorie against ICMR standards of 1250 calories for children at the age of 1 & 1650 calories for those below 5, causing irreversible damages; Budget allocation less than 1% for children under 6, but writes off US 537 billion in 6 years as corporate tax exemptions and reliefs; Businesses then opposes government welfare schemes for the poor; Governments cites lack of funds as the primary reason for rejecting demands like universalisation of ICDS; Government promotes a targeted approach for key social welfare schemes and remains non-committal on nutritional Security in the National Food Security Bill 2011. Perspectives on childhood hunger Womb to grave: Malnourished mothers – condition deteriorates during infant/young feeding, most perish; Causes disability; The families caught in the web of displacement and distress migration complicate the situation; Diseases; lack of access to primary health services; sanitation; Contrasts state obligation to protect rights and guarantee health; Nutrition programme focuses on delivering cereals occasionally (as calories should come from varied sources ranging from fats to fruits), lacking universal coverage and adequate resource allocation (US $ 0.12 per day per children); Institution and market-based approach to deal with micronutrient fortification and medicalisation of Food ; Why? Governance by consultation has stopped; NFSB 2011; Only English language version of the Bill was available on WEBSITE; for a period of 25 days; no discussion out of the Parliament; advertisement published in 12 newspapers; 9 were English; when a people’s organisation takes this to the people; defined as threat to the State; Annual budget is consulted with corporate entities not with farmers; even no scope for MPs; Five-year plans made by Planning Commission, decides how 35% of India’s budget to be spent; without any discussion in the Parliament; Public opinion should find respect or not?? GDP Vs Hunger Growth-based development concept does not decline malnutrition; GDP Growth rates (2001-2010) – 5% to 8.5% Malnutrition declined – 0.1% per year or 1% decline in 10 Years Nutritional poverty – increased from 64% to 80% Increasing divide between RICH and POOR; where RICH are being treated with EQUITY in GROWTH, whereas POOR are treated with most MINIMUM WAGES. The Buffer Stock Buffer stock of food grains ~31 million tonnes to deal with emergency, to keep market prices stable and to feed people in different conditions. The food grain is procured from farmers on MSP in crop seasons every 6 months; BUT State has stocks of 85 million tonnes of food grain; if you pile-up food-grain bags one above the other, it can reach the moon -thrice; It is rotting, Supreme Court asserted that state cannot let people die of hunger amidst this rotting of food and directed it to distribute it among the people but PM said don’t interfere in policy matters. I do not see malnutrition as an accident. Nor is it caused by any disease agent like a bacteria or virus. It is a ‘systemic’ disease, the inevitable outcome of the low priority the state accords to food security. It is the outcome of children not getting nutritious food according to their developmental needs for long periods of time – or sick children not receiving proper medical and rehabilitative care. In its initial phase, malnutrition does not require medical intervention. What is needed is just plain, wholesome, nutritious food. A weakened physique lowers immunity, ensnaring children in a web of infection and making them susceptible to illnesses such as diarrhea, pneumonia, and measles. Their physical and mental development is arrested and if their condition degenerates to a critical level, death will result. It is not a coincidence or chance that the largest number of deaths in the world from pneumonia and diarrhea occur in India. Malnutrition needs to be seen as a social and economic crisis that robs people of their ability to contribute their mental and physical labour for the well being of society. The State’s policy priorities There is a pattern behind the contradiction between ‘want’ amidst ‘plenty’ Agriculture Rs. 20208 Crore US $ 3742 Million Child Survival Rs. 16500 Crore US $ 3055 Million Health Rs. 30702 Crore US $ 5685 Million Defence Rs. 193407 Crore US $ 35816 Million So the question we need to answer here is: Why is malnutrition endemic in India when the country is witnessing unprecedented progress, clocking the highest-ever growth rates since independence? Heads Allocation by the Government of India 2012 Before seeking an answer to this question, here are a few more statistics: An estimated 60 to 65 million people are displaced in India since independence, the highest number of people uprooted for development projects anywhere in the world. This amounts to around one million people displaced every year since independence, says a report by the Working Group on Human Rights in India and the UN (WGHR). Over 22 million people migrated from rural areas to urban areas over the past decade, the net migration share of ruralurban migration in urban growth increasing to 24 percent from 21 percent in the previous decade. For the first time since 1921, the urban population grew more than the rural population in the decade (increase of 91 million in urban vs 90.6 million in rural population) suggesting that distress migration may be a contributory factor propelled by a reduction in common property resources and livelihood means in rural areas. As many as 225,000 farmers have committed suicide in despair at their economic plight during the current period of India’s explosive growth and bumper harvests and seven million people for whom cultivation is the main livelihood quit farming in the decade covered by the 2001 census – averaging over 2,000 per day. This is a direct result of indebtedness to both financial institutions and moneylenders. The minimum support prices for different food grains announced by the government are usually below their actual production costs, rendering farming uneconomical. For example, the maximum selling price (MSP) for a quintal (100kg) of wheat was Rs. 1,000 when the cost of production was Rs. 1,543.93 (Economic Survey 2010-11). The government has consistently exceeded its procurement target for food grains for the public distribution system (PDS) in recent years. The 75 million ton purchased this year is several times more than its June 2012 target. There are no enough warehouses to store this grain so around 25 million tones are kept in temporary open storage. Over the past four years, 5 million tones of food grain have rotted in open storage, leading the Supreme Court to make some caustic observations on the issue and urging the government to distribute the grain among the poor instead of letting it rot. But the Prime Minister, who terms malnutrition a ‘national shame’, told the court that the grain couldn't be distributed because of policy issues. So what are the policies of the Indian state that lay the ground for such contradictions, forcing people to migrate, displacing them from their homes, compelling them to commit suicide, and denying them the right to food security and health while the country clocks 7-to-8 percent Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates? What are these policies that let food grain to rot but prevent the state from distributing it among the poor and starving? An underlying pattern is evident, an economic and social dichotomy in Indian society that has been exacerbated by the neo-liberal reforms of the 1990s. It is a pattern in which precious natural resources are diverted at throwaway prices to the corporate sector, which is also given concessionary land and tax holidays in name of economic growth and development but cries itself hoarse at the ‘wastage’ of financial resources diverted to food subsidies for the poor and fertilizer subsidies for the farming sector. It is a pattern in which the state progressively abrogates its constitutional responsibilities to the people through privatization of its social welfare activities, that exposes the poor to the supply-demand compulsions of market forces. The popular media highlights this dichotomy as the two Indias – India of the haves and the other of the have-nots, one getting richer, and the other poorer. In 1947, the people visualized the state playing the role of a guardian looking after the interests of the people. This idealistic belief saw the state progressively gaining ascendancy over the society and abrogating its responsibilities by fashioning policies to hand them over to other socio-economic structures. Society believed the state would be accountable and the people would remain its central concern, with the deprived sections receiving special attention and protection to ensure that inequality, exploitation and discrimination are eradicated. 69 grams in 1961 to 31.6 grams in 2010 500 475 450 425 2010 2007 2004 2001 1998 1995 1992 1989 1986 400 1983 Corruption is a continuing sideshow in the development march 1961 – 399.7 grams to 1991 – 468.5 grams to 2010 – 438.6 grams Pulses; Decline in availability; 1980 Between its daily battles and nightly dreams lies a vast chasm. In India, that chasm is called development. Cereals; Decline in availability; 1977 Behind this new middle class of the emerging capitalist order stands the forgotten class. It is a class that lives with the bitter everyday reality of wondering whether it will get work for the day and whether it will be able to meet its daily needs. It is a class that dreams at night that its young ones will sleep without starving and will get proper medical care when they fall ill. Per capita daily availability of Foodgrains 1974 Instead, modern concepts of development have seen the private sector, once protected by the state, emerging as such a powerful force that even the state finds difficult to control and rein in. The singular concern of state policy is to look for ways to achieve a higher growth rate, not to provide equal opportunity and access to the fruits of economic development. This approach has seen the emergence of a consumerist middle class that does not concern itself with the fact that the indulgences it enjoys cloak an insidious process of resource exploitation that is taking place on a national scale. There is another common deterrent that spans the two Indias and act as a brake on progress and equity – corruption. I will not go into details on this issue but let me briefly quote two examples linked to healthcare and malnutrition - the central focus of my article - before analyzing the social impact of the two-Indias’ dichotomy. It is a well-known fact that like malnutrition, corruption is endemic in India. According to Transparency International, India scores 3.1 on a scale from zero to 10 in its corruption perception index. The country ranks 95th among the 183 countries ranked in the 2011 index. In the state where I live, anti-corruption raids conducted against senior officials of the Health Department, between 2009 and 2012, led to the seizure of property worth Rs. 2.8 billion – far in excess of their known sources of income. Similar seizures from officials responsible for child nutrition programmes amounted to Rs. 3 billion. But these raids did not lead to any punitive actions. Similarly, the chief official of the Indian Medical Council (IMC), who oversees medical education in the country and is currently encouraging privatization in that sector, was found to be demanding Rs 10-to-15 million from candidates seeking a seat in private medical colleges to study for a medical degree. I leave it to you to dot the i’s and cross the t’s to see how such corruption affects healthcare in India. Food security and health are not rights but left to the mercy of market forces On the policy front, one aspect is clear. You cannot remain neutral when political, economic and other considerations favour specific sections of society and further their interests. You need to take a stand. It is clear what stand Vikas Samvad, a civil society group, takes. It is the stand of those who face discrimination in sharing the fruits of development - dalits and adivasis, women and children, the aged and differently abled. It is the side of 77 percent of the Indian people who achieve the feat of spending less than Rs. 20 to meet their daily life needs. It is the side of 80 percent of the population that is denied nutrition and calorific energy that India’s National Institution of Nutrition (NIN) says is the minimum daily per capita requirement. The basic framework for policy-making by the government is laid down in the Indian Constitution. This document defines a set of fundamental rights, which are inalienable political rights of citizens that the state is duty-bound to protect and implement. These rights are defined and interpreted as justiciable, meaning that it is every citizen's right to realize them without exception as enforceable guarantees. It includes the right to life. The denial of any of these rights in whatever condition or extent translates as injustice upon the citizen by the state. The constitution also categorises certain social and economic rights that form part of the Directive Principles of State Policy. The state can formulate policies governing these rights but is not obligated to ensure their implementation. The right to health and nutrition fall in this category, so does the right to maternal health and protection. This distinction has serious implications on how the healthcare system has evolved in the country and how the system continues to discriminate against and alienate the poor. Civil society groups are increasingly questioning how the right to life – a fundamental right that the state is duty-bound to protect - could be guaranteed without the right to health and nutrition? As long as health lacks the status of a fundamental right, policy making will continue to be swayed by considerations other than social justice and equity. Law does not define health but healthcare is implemented through state missions and planned programmes. The declared national objective is to achieve the UN’s Millennium Development Goals but the state has not taken up any national campaign to reform and strengthen the condition of the existing healthcare system, barring the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). Primary healthcare is a shambles while specialist care remains a distant dream for the people. Medicines are unavailable in healthcare facilities, which are grossly understaffed while sanctioned posts of doctors, nurses and health workers lie vacant. There are no constitutional provisions to compel doctors and other health personnel to serve in remote rural areas. The expenditure on health averages 4.5 percent of the GDP but the state contributes only 1.5 percent of this amount. Even more unbelievable is the fact that its contribution to expenditure on medicines is a miniscule 0.1 percent of the GDP. Seen in monetary terms, the per capita expenditure on health was around Rs. 2,500 in 2011. Of this, the government contributed Rs. 675 through its health services, the remaining Rs. 1,825 are to be met by the people. The per capita expenditure on medicines was just Rs. 43 - Rs. 40.59 (3.58percent) in villages and Rs. 62.05 (3.12percent) in cities, of which only 5.4 percent was distributed free. India needs an additional 2.47 million doctors, nurses, and health workers to strengthen its healthcare system. If the planned infrastructure is put in place, these figures would go up to 6,26,000 doctors and 4.97 million health workers. According to a Planning Commission report, the country needs 187 more medical colleges, 383 nursing schools and 232 ANM schools to fulfil the its requirements. But there is no sign of any inclination to set up this infrastructure. Instead, medical education is seen as a profitable trade in India so it is witnessing rampant privatization. Anyone seeking a medical degree has to spend anywhere between Rs. 3-to-5 million, with postgraduate qualifications requiring another Rs. 3-to-12 million. That precludes medical graduates joining the government health systems. Privatization has made inroads into the entire healthcare system, pointing to policy making paying homage to market forces rather than focusing on people. The Planning Commission Expert Group points out that 80 percent of health services for out-patient care in the country is now available in the private sector, while 60 percent of the population goes to private sector hospitals for inpatient care. People also pay 79 percent of their health expenditure from their own pockets. More distressing, 68 percent cannot access private healthcare services because they cannot afford to pay the fees or buy the required medicines. The largest household expenditure is on health-related needs. Because the poor cannot get loans from institutional sources they approach local moneylenders who proffer loans at annual interest rates that can range from 36 percent to as high as 120 percent. Such loans to meet medical expenses are the single biggest cause of debt in the country. A study by the Centre for Insurance and Risk Management and the International Food Policy Research Institute conducted in June 2011 in two districts of Madhya Pradesh found that 40 percent of rural families face an economic crisis every time a family member falls ill, the indebtedness per family being Rs. 78,828 on average. Health insurance does not seem of any help to the poor. It can be a viable strategy to ensure healthcare only if the premiums are within the economic reach of people. This can only become possible if the cost of treatment comes down. But the health sector has become a profit centre in India today. Health services are among the costliest services in the country. The health insurance sector is also guilty of short-changing the people. Instances of the medically insured not getting the promised treatment abound. There is corruption at every level in the claims process. First, it is difficult to get the benefits and even when the benefits are available the insurance agent claims a share of the amount disbursed. As a result, people tend to exaggerate their claims, knowing that a portion will be expropriated, and this is how the system breaks down. It is not easy to benefit from medical insurance in India. A perusal of the insurance documents reveals that there are nine points relating to instances where the benefits can be availed of and 33 points of instances where no benefits are forthcoming. It shouldn’t therefore come as a surprise that infant mortality does not come within the purview of medical insurance even though 54 percent of child mortality relate to deaths of newborns aged below 28 days. The truth is that providing treatment services available is not the priority of the insurance market. Moreover, navigating the system is difficult because the procedures are so involved and complicated, and with premiums being so high, medical insurance is outside the scope of most people, especially in rural areas. Poverty line excludes millions from nutrition and food security The process of exclusion and discrimination is carried forward in arriving at an official definition of ‘poverty’. In India, poverty is defined by the ‘poverty line’, which marks the cut-off point separating the poor and needy from the rest of the population. It is a politically sensitive line. Since the 1970s, the cut off mark was determined on the basis of a minimum standard per capita calorie intake. According to the government’s Expert Group, people living in rural India require 2,400 calories of energy to fulfill their daily needs while those living in cities require 2,100 calories. The government used the daily per capita expenditure required to ensure this minimum calorie intake as the statistical measure to calculate the poverty line. But it included other social welfare requirements such as education, health, communication, transport, leisure etc in the permutation. The low quantum of the daily per capita expenditure taken as the standard by the government has always been a contentious issue, given the rising costs of the standard of living. Around 36 percent of the population was enumerated as being below the poverty line in 1997. This figure declined by 10 percent to 26 percent in 2002. Therein lies a tale. In 1997, the government lowered the daily per capita expenditure standard it had fixed for drawing the poverty line. The ostensible reason given was for better targeting of its anti-poverty programmes to the neediest but alternative explanations can also be attributed to its action. For example, the government may have wanted to showcase the success of its neo-liberal economic policies by claiming a significant decline in poverty in the country. Or else, it may have wanted to ensure that it is accountable to as low a percentage of the population as possible. This poverty estimation was challenged in the Supreme Court in 2002 by the Right to Food Campaign, a civil society group, forcing the government to retract in 2006 and accept that poverty had not declined, the percentage below the poverty line continuing to be 36 percent. In 2010, the government issued a fresh poverty estimate – 32 percent below the poverty line. This estimate was also strongly opposed by civil society groups. Their argument remained unchanged. They pointed out that the malnutrition percentage had not fallen and starvation was on the increase with foodgrain prices rising 80 percent. Moreover, 45 million people were looking for employment in a situation where jobs were available for only 2 million people. So by what magic wave of the wand had poverty declined in such a scenario? Ironically, it was the report of another government agency that conducts periodical consumption expenditure surveys and puts out figures on the per capita calorie intake of Indian households that raises doubts about the government claim. The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) pointed out in its Nutritional Intake in India 2012 report that 80 percent of the country’s population did not get adequate nutrition (minimum standard calorie intake). Today, the Planning Commission’s latest assessment says 29.7 percent of the Indian people live in poverty. It says a family living on a daily income of less than Rs22.42 per capita in rural areas and Rs28.65 per capita in urban areas could be categorized as being below the poverty line. At current prices, wheat costs Rs15 per kg, rice Rs20 and pulses anywhere from Rs50 to Rs70, and public transport Rs1 to Rs3 per km. This low ‘poverty line’ would automatically exclude a significant percentage of the population. If we accept that eight in every 10 people do not get adequate nourishment, it means 50 percent of the population is excluded from the poverty list and become ineligible for a host of social welfare benefits that include subsidized rations. This adds up to 610 million people, which includes 84 million children, who are being pushed to the margins. Can we ever hope to be free of the scourge of malnutrition in these circumstances? Below Poverty Line – Eligibility Criteria India follows a targeted approach since 1997 for Health, Food and Social security, where only POOR are to be ENTITLED; Till date not able to define who is poor!! States & Union Territories who, according to the learned Attorney General, had not identified the below poverty line families under the Antyodaya Anna Yojana, to identify, we are not satisfied that any such exercise in the right earnestness has been undertaken. ----- Supreme Court of India, 17th September 2001. Still Government of India is at the same stage and society at large living with hunger; And what is worst! Nutritional deficiency kept on Developing Population not receiving adequate nutrition 1983 – Nutritional Poverty 64.8% but expenditure poverty was estimated 56% 1987 - Nutritional Poverty 63.9% but expenditure poverty was estimated 51% 1993 - Nutritional Poverty 67.8% but expenditure poverty was estimated 45% 1999 - Nutritional Poverty 70.1% but expenditure poverty was estimated 36% 2004 - Nutritional Poverty 75.8% but expenditure poverty was estimated 28% 2010 - Nutritional Poverty 80.0% but expenditure poverty was estimated 37.2% 2011 – Planning Commission says now 29.7% The peg the poverty line at $ 0.53 or Rs. 28 in urban areas and $0.41 or Rs 23 per day – Decided by the planning Commission!! Nutrition is more than a health issue in the politics of development Equally contentious is the issue of what constitutes nutritious and wholesome food. When the government launched the ‘green revolution’ in the 1960s, it ushered in a sea change in agricultural production and productivity for cereal crops, first for wheat and then rice. But pulses, oilseeds, fruits and vegetables were overlooked in this initial research and planning thrust. The consequences can be seen in the government’s public distribution system as well as the nutrition programmes it has launched. The PDS is based exclusively on distributing subsidized wheat and rice – which account for 78 percent of India’s total food grain production - to the people. Wheat and rice may fill one’s stomach but we shouldn’t forget that in addition a person needs to consume dals, milk, animal products, vegetables, fruit, tubers, oil and beans to ensure adequate nutritional intake. If children do not get adequate vitamins, fat, carbohydrates, proteins and minerals they cannot attain the normal physical and mental growth expected at their age. The National Family Health Survey shows that only 7 percent of the population gets to eat eggs, fish, chicken or other meats daily, while 39.8 percent of women and 46.7 percent of men consume some amount of milk or dairy products, and 36 percent of women and 41 percent of men do not get green vegetables daily. NSSO data shows that 80 percent of the population has a daily energy intake below the official standard, ranging from as low as 1,545 calories among the poorest to 2,184 calories. NIN and other government data shows that the shortfall in the case of children ranges from 550-to-1,000 calories. The poorest 10 percent spends just Rs. 294.03 per capita per month (72.7 percent of total income) on food, mainly cereals, to get this 1,545 calories, plus 40.7gm of protein. Compare this with the top 10 percent that spends Rs. 1,156 per capita per month to get 2,617 calories plus 73.8gm of protein. On average, 57 percent of the monthly per capita expenditure in rural areas (Rs. 600.36) and 55.6 percent in cities (Rs. 1,103.63) goes for food alone. The 2001 PUCL right-to-food litigation had one highly positive outcome - the Supreme Court directed the government to implement the highly popular midday meals scheme pioneered by the Tamil Nadu government and adopted by several other state governments for all primary school children in the country. The National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education now provides cooked meals to the schoolchildren, the prescribed norms being 450 calories of energy, 12gm of protein and quantities of micronutrients like iron, folic acid, vitamin-A, etc. However, corruption has extended its tentacles into the scheme in many regions. The government now at least accepts that wheat and rice alone cannot guarantee food security and balanced nutrition. It is now embarking on a second ‘green revolution’ in pulses, oilseeds, fruits and vegetables. But a question mark still remains over the ability of the PDS to reach such nutritive foodstuff to the people. More contentious is the view that is gaining increased currency today of incorporating special micronutrient-enriched products in the management of food security and malnutrition. This includes supply of wheat flour fortified with micronutrients instead of wheat through the PDS. It also includes the possibility of fortified packaged food being supplied to children under the midday meal scheme. This throws an open invitation to the private sector to enter the food trade with fortified canned foods and nutritional supplements for the management of food security. Some international funding and health agencies are in fact trying to convince the government that malnutrition can be eradicated with a handful of these special products. The language increasingly in use today includes examples such as ready-to-use therapeutics, ready-to-use food and energy-dense food. Systemic barriers intrude in providing healthcare for children and mothers Let’s now take a closer look at the status of women and childcare. We know that 90 percent of physical and mental growth occurs in the first five years of life so children aged below five years need to be assured food and nutrition security if they are to achieve normal physiological and mental growth and not suffer the consequences of malnutrition and stunted growth. The government launched an Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) in 1975 to combat the scourge of malnutrition. The world’s largest universal nutrition and childcare programme took a holistic approach by factoring in nutrition schemes for pregnant and nursing mothers, pre- and post-natal medical investigations and vaccination. An analysis of the situation prevailing 37 years ago had shown that children faced a 300-to-500 calorie and 8-to-12 gm protein deficit in their diet, which the ICDS sought to bridge. But the scheme never achieved its potential and soon fell into disarray because it never figured high in the priorities of the state. Children do not constitute vote banks. Also, with privatization and revenue generation concerns coming into focus under the market-oriented reform policies of the 1990s, resource and infrastructure investment also tended to peter out. Budget allocations were contradiction-ridden and often without logic. During a period when the wages of government employees (an important vote bank) rose 100 percent (1991 to 2005) the daily allocation for nutritious food per child under the ICDS remained a dismal one Rupee. That adds up to 0.7 percent of the budget being allocated to a segment that constitutes 17 percent of our population. An analysis of the ICDS reveals that until 2004 not more than 35 percent of the target children had been covered by this universal nutrition and healthcare scheme. Among these, only 25 percent benefited from the services rendered under the scheme. There is another problem as well. When it comes to maternal health, gender discrimination is a huge challenge. Women are not free to choose nor are they treated as equals so that limits their right to health. Our society is reluctant to even discuss the issue of women’s health. The family priority is to hide whatever is happening when girls reach puberty and experience physical and mental changes. Since women are not seen as contributors to family income, their claim to health and nutrition is further limited. This is why the main causes of maternal deaths are malnutrition, anemia, stress and excessive bleeding. India had a National Maternal Assistance Plan under which pregnant women below the poverty line were entitled to a one-time payment of Rs. 500 two to three months before their delivery to enable them to get the required nutrition and medicines during their pregnancy. The government shut down the programme in 2007-08 citing social realities and launched a new initiative – Women’s Protection Plan – in which pregnant women who delivered their child in a health centre could claim a one-time payment of Rs1,400. Shutting down a programme that promised pre-delivery nutritional assistance and encouraging institutional deliveries when the healthcare system is in disarray and transport is unavailable is a double blow for women. It is obvious that the thrust of the new programme merely seeks to meet mandated millennium targets of institutional deliveries. There is also a hidden agenda – sterilization, which forms part of the package for women coming to health centres for delivery. Now consider this example of reinforcement of gender stereotypes. Given their social status, women have to constantly confront male violence and dowry demands in marriage. In this scenario, the Madhya Pradesh government launched a Kanyadaan Plan under which women are given a sum of Rs. 15,000 to celebrate a traditional, dowry-based marriage. Not just this, every symbol that is used, perpetuates this system of bondage. Like the ICDS, there have been other initiatives that have begun with lofty objectives. One such positive development is the initiative of the Madhya Pradesh government launched in 2009 to establish intensive care units for newborns in all district hospitals. This should be seen, as an important step because 50 percent of newborn deaths occur within 28 days of birth anda large percentage of families cannot afford medical treatment of the newborn because it is expensive. The NRHM is the other noteworthy attempt to bring some improvements and reforms in the healthcare system by integrating all vertical health programmes of the Departments of Health and Family Welfare, including the Reproductive and Child Health Programme and various disease control programmes. One objective of its Janani Suraksha Programme is to increase institutional deliveries, which is also one of the millennium goals. It is said to have achieved striking results within a short span of time. Madhya Pradesh also lays claim to achieving 90 percent institutional deliveries (of around 1.65 million childbirths) in 2011-12 under the programme – against 26 percent in 2006. But here one needs to look a little more closely at this statistic because the state has one hospital bed for every 2,300 people in urban areas and one per every 5,000 people in rural areas. The nearest community health centre (meant to cater to a population of 30,000 people) for a pregnant woman to have a safe delivery is, on average, situated 30km away and getting transport to reach the centre still remains a big challenge. One could also ask who is delivering these babies when 345 out of the 636 sanctioned posts of women’s health specialists (54.2 percent), 250 out of 573 posts of child health specialists (43.6 percent) and 148 out of 308 posts of anaesthetists (48.1 percent) lie vacant? The state has sanctioned the appointment of 6,000 doctors in its health services yet 2,200 posts (36.6 percent) remain unfilled. A study of government data on institutional births done by Vikas Samvad reveals that there were 1.21 such births reported in 2010-11, which means every doctor was expected to attend to an average of 1,823 deliveries - with one specialist reported to have attended to 4,119 childbirths. There is another reason to doubt the government claim. National Health System Resource Centre statistics show that Madhya Pradesh registered 719 maternal deaths during 2010-11, of which the cause of death was stated as ‘unknown’ in 51 percent of the cases. The maternal mortality rate in the state is 269 per 1,000 live births, which means it averages 4,400 maternal deaths a year. That points to only 17 percent of the deaths occurring in the institutional care system. As for childcare, if we check the child death statistics in the state it becomes obvious that the healthcare system is not reaching children either. As per the mortality rate of children aged below five years, a total of 160,000 deaths occur every year in the state but only 16,110 child deaths were reported in 2010-11, of which the cause of death was stated as ‘unknown’ in 8,356 cases (75percent). The state spends a dismal Rs. 52 per year on its 20 million children aged below 12 years. Of the sanctioned posts of 572 child health specialists' 250 posts (43.7 percent) lie vacant. The language we speak and the demands we wish to make of the system Hunger and food security are major political and social issues today. The state is in the process of passing a Food Security Act but this legislation stops short of defining nutrition as a basic right. That seriously limits its purview. This limitation is best exemplified in the title of the chapter ‘Agriculture and Food Management’ in the government’s annual Economic Survey (2011-12). There is a world of difference between ‘food management’ and ‘food security’. The Act is limited to ‘managing’ food –providing people living below the poverty line with a fixed amount of cereals, with no mention of pulses, oilseeds and other foodstuff. It does not concern itself with the root causes of malnutrition, which is an endemic condition linked to deprivation, poverty, exclusion, food insecurity, and inequitable use of resources. As part of the management approach, the Act talks about providing readymade meals (packaged food) for the midday meal programme. It also gives the government the option of supplying wheat flour in place of wheat through the ration shops, laying the ground for giving legal sanction to adding micronutrients in the flour. These provisions give the government a handle to implement a system where packaged foods and nutrient supplements and additives are manufactured and supplied by private sector companies. The private sector and funding agencies also talk about managing food security and seek to establish a charity perspective of serving the people. We speak a different language. We talk of people’s rights. We feel that the most appropriate management, treatment and prevention of malnutrition can only be done at the community level. As a responsible civil society and citizens group we have been fighting for the adoption of such a community-based management approach at the policy level. The reality that faces us is that according priority to factory-produced packaged and fortified foods and market forces will influence and disrupt community responses and behaviour as well as traditional household food security practices. The technical details specified by the Act (for example, that midday meals should contain 50 percent of the required micronutrients) will lead to centralisation of the child nutrition programme, with no role left for the mahila mandals and self-help groups, which would go against the Supreme Court stipulation that these institutions be given the responsibility of preparing hot cooked meals. Our demand is to keep food security out of the domain of the private sector and let the community gain greater control of resources, with the state guaranteeing equitable resource use and protection of agriculture. The cycle of malnutrition begins when we seize natural resources from traditional control and management that is based on their sustainable use. The community should give shape to a sustainable food security system based on its traditions and environment. Food security is not limited to just procuring food grain. It is also important to ensure that every individual gets food and nutrition according to his/her needs. For infants aged below six months, it means being breastfed by their mothers for at least six months. Between the ages of six months and two years, infants should have soft, semi-liquid food that is easy to eat and digest, yet contains the required nutritive elements. People performing hard physical labour require at least 50 percent more food and nutritive elements than those not doing such labour. The needs of the elderly are also different. As for those suffering from tuberculosis, cancer, HIV and other serious diseases, food security means getting adequate nourishment to ensure that the effect of their medication is not diminished and also ensuring they get both food and medication at the proper time. Our demand is that given the current gravity of the situation, the government raises the daily per capita expenditure on children from the present Rs. 8 to a minimum of Rs. 25. This would require a budgetary allocation of Rs. 1.35 trillion. This is not as impossible a sum as it looks if we compare it with the income tax, export-import tax and trading fee concessions and grants totalling Rs. 27 trillion extended to corporate entities between 2006 and 2011 in the name of catalyzing economic growth. These concessions cover automobile production, jewellery exports and 5- and 10-year tax holidays for industries. This is yet another of the policy contradictions that riddle the Indian scenario. The nation pleads paucity of resources to allocate money for our children in distress but is generous with its doles to the corporate sector. We believe that nutrition; food security; education; health; and livelihood should be excluded from the purview of the poverty line. This would be a first step in the direction of making these rights inclusive and universally available. Without such inclusion, development will remain an empty word. The state must play the role of an active participant in this process. It is the constitutional role of respecting people’s right to food and ensuring that no individual goes hungry. For this it should formulate the appropriate laws and policies for production, procurement, warehousing and distribution of food to ensure social justice for the people. We also need to strengthen the framework of our primary healthcare system and ensure that adequate numbers of health personnel are duly appointed to run the system efficiently. Health services should be reached to inaccessible regions and specialist services should also be developed. Until and unless we have a carefully monitored system that is answerable for its actions and there is an effective complaint redressal mechanism people will not receive proper healthcare services. We must always remember that we cannot remain neutral if the outcome of our policies is widespread hunger and starvation for large masses of people. The first to suffer the consequences are the children because hunger first sinks its teeth into and feasts upon the most vulnerable section of our society. Structured denial of ACCESS INDIA - Public Health in 2012 Reference – Women and Child Health Supreme Court of India intervenes – “(the) right to life guaranteed in any civilised society implies the right to food, water, decent environment, education, medical care and shelter” Chameli Singh & Others v. State of Uttar Pradesh, (1996) 2 SCC 549 However no parts of basic, primary, public and essential health services are covered by the law. Points to be highlighted: People stuck in a vicious cycle of hunger & chronic poverty on one side; State privatising primary health considering it the best policy. Expert group on health set up by Planning Commission in its report last year claimed that 80% of health services for outpatient care in the country are in private sector; While 60% goes to pvt. sector hospitals for in-patient treatment; People also pay 79% of their health bills on their own; 68% people cannot access private health care since they cannot pay; India spends 4.5% of GDP on health; state contribution in it is less than 1.5%; and on medicines the state expenditure is 0.1% of GDP. GROWTH is translated into the paradox of epidemic outbreaks rising from 553 in 2008 to 990 in 2010 A Case Study – Madhya Pradesh Central India with a population of 72.5 Million (2011 Census); Malnutrition under 5 yrs – 60%; Stunting is on rise; 7 million households under the distress poverty; IMR – 62 and MMR 325; Average live births – 1.66 million a year; Infant Deaths - 100000; actually registered 23000; Maternal Deaths – 5395; actually registered – 700; Food insecurity – acute; Rs. 52 or less than US$ 1.00 allocated for child health; Calorie intake decreased from 2423 in 1972-73 to 1939 in 2010; decline in protein intake from 63 to 58.4 grams; Total monthly per-capita expenditure – (rural) Rs. 902.82 per month; of which Rs. 503 goes on food; they spend Rs. 37.39 on education and Rs. 56.91 on health; Highest IMR and one of the highest MMR in India; Gynecologists - out of 662 posts 339 vacant Child specialists – out of 640 posts 321 vacant One gynecologist covers 4119 deliveries NRHM says causes in 61% child death cases are not known. A Expanded Case Study – India 2012 UNICEF study – 6,09,000 of 2.197 million child deaths worldwide due to pneumonia and diarrhea in India; 79% child deaths are due to 4 preventable diseases – malaria, diarrhea, measles and pneumonia; Malnutrition is a direct and indirect cause of child deaths in 56% cases; Only 1.5% of the GDP is spent on public health; and India needs 2.47 million doctors, health workers and nurses; we would need 187 medical collages, 383 nursing collages and 232 nursing schools with highest capacities……BUT India plans to sub contact this to private sector; this sector in itself incapable to cover this gap due to various reasons. Constitutional and Legislative framework The Indian Constitution prohibits discrimination and recognises all human rights; Civil and political rights are recognised as directly justiciable fundamental rights; Economic, social and cultural rights are defined as directive principles of state policy; Article 47 of the Constitution states: “The State shall regard the raising of the level of nutrition and the standard of living of its people and the improvement of public health as among its primary duties.” Government = Freedom from hunger is not (a) RIGHT The right to food is not directly justiciable; its inclusion in the directive principles of state policy serves to guide interpretation of fundamental rights, including the right to life protected by article 21. The Constitution provides special protection for women and children (art. 39 (f)) as well as for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (art. 46), prohibits discrimination, including in the use of public sources of water (art. 15.2 (b)), and abolishes untouchability (art. 17) But Judiciary asserts that it is!! “In our opinion, what is of utmost importance is to see that food is provided to the aged, infirm, disabled, destitute women, destitute men who are in danger of starvation, pregnant and lactating women and destitute children, especially in cases where they or members of their family do not have sufficient funds to provide food for them. In case of famine, there may be shortage of food, but here the situation is that amongst plenty there is scarcity. Plenty of food is available, but distribution of the same amongst the very poor and the destitute is scarce and non-existent leading to malnourishment, starvation and other related problems.” Supreme Court of India; PUCL Vs. Union of India and Others; 23rd July 2011 In the END Chronic hunger is a silent killer. A report prepared by MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, titled ‘Food Insecurity Situation in Madhya Pradesh’, describes the linkages of human capital and economic development with malnutrition. The report states that “individual food insecurity may start in an unborn child as foetal under nutrition. It takes the form of low birth weight babies, under nourished children and adults. The ultimate severe form of food insecurity is starvation death. One need not be complacent if there is no starvation death. Silent hunger caused by malnutrition and diet deficient in essential nutrients, is more damaging to human capital and economic productivity of the nation.” This analysis is, however, not the end of the damaging story of chronic hunger in the second fastest growing economy of the world. It merely reflects one segment and ramification of the total disaster. A question that is to be asked is why this situation emerges and how it continues in a country; that one which is considered to be a democracy? It is a fact that the state cannot deny the fact that malnutrition and chronic hunger has been a problem for a very long time. At a point state develops welfare programs for the people; termed as social sector programs. These programs; in a general term have entitlements to be delivered; but it does not bound the state to bring change in the situation. There may be a series of excuses of which the lack of resources most commonly quoted. However the resources the state spends on other counts, for instance defense is incompatible with such an excuse. Inequality, Exclusion and Unaccountability are also the key causes of Malnutrition; these have been discussed and debated widely academically but not addressed in the Governance systems and that is why at the end of the day no one in the system is responsible for the mortality and morbidity here. The another issue lays in the resistance of the policy makers; there has been knowledge that the war against malnutrition can only be fought at the community level but community based and decentralization approach is seriously missing in all actions. Most of these programs are target based; designed for a particular group or section in the society; like poor, indigenous or dalits. At the end we learn that the state fails in identifying the people for those their lives are to be benefited through these programs. In this process a large section gets excluded because of faulty indicators, and un-eligible persons being provided with the services and entitlements, although we must say that is not the central problem. The problem is that the state agrees on the issue but denies its structural causes. Today India has the biggest food and nutrition programs, which are designed to protect children and the most marginalised from hunger; but entitlements under these programs, are not conceived as central in guaranteeing human rights and justice. Entitlements for children are mentioned; but state never guarantees that these will reach to the people. India accounts for the highest number of infant and child mortality, globally. However until today there has been no statement by the Parliament of India or by any political party that freedom from hunger of the children must be the struggle for freedom; because persisting hunger will prevent a large section of the society to enjoy the true fruits of the freedom obtained in 1947. India has registered much higher number of deaths of children than the total number of people killed in all wars in last 20 centuries. Do we still need arguments and facts that why we should invest more in food than in weapons? Statements are made from the front that malnutrition is a national shame on occasions like the Independence Day. However state polices and plans are made to sustain the hunger and malnutrition. The country's economy grows rapidly. But inequality widens and injustice becomes a regular feature. The people still are still seeking freedom from hunger and injustice and this freedom is to come from WITHIN;