Mercosur

A turning point?

Jul 5th 2007 | BRASÍLIA AND BUENOS AIRES

From The Economist print edition

A falling-out with Hugo Chávez could be good news for a paralysed trade

group

THE most notable thing about Mercosur's presidential summit held in Asunción,

Paraguay's capital, on June 29th, was an absence—that of Hugo Chávez. Venezuela's

strident left-wing president chose to spend last weekend in Moscow and Iran,

shopping for arms and for friends. Without him, the Mercosur meeting was much

quieter. But South America's biggest trade block, beset by bickering and backsliding,

is still a long way from regaining the

importance it had in the 1990s.

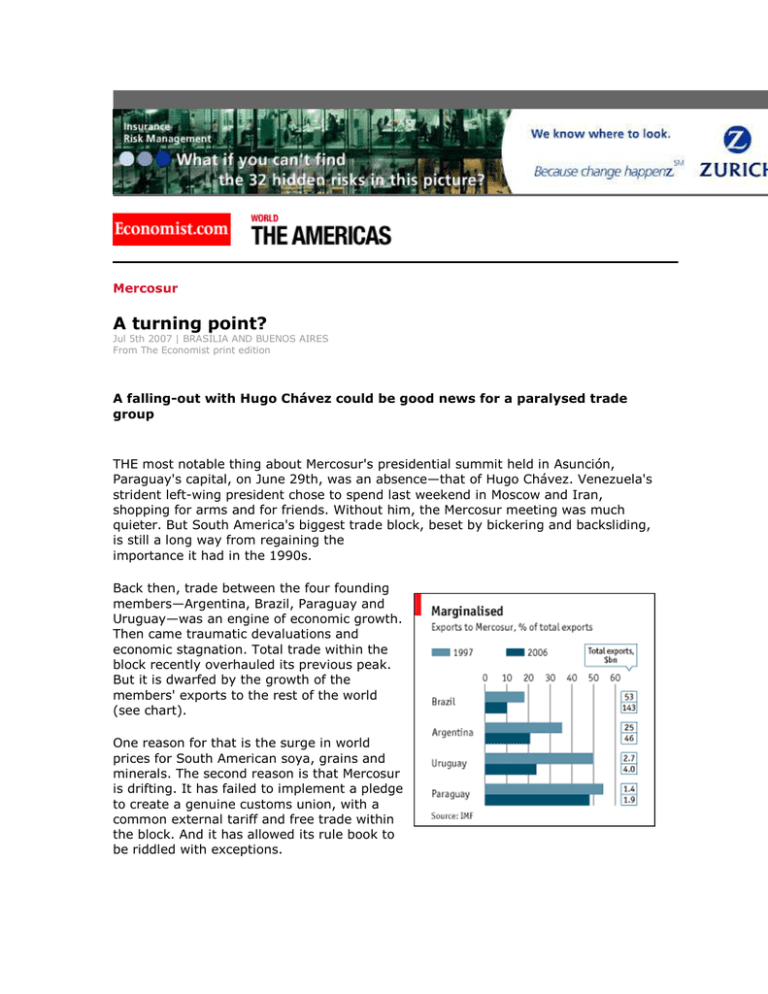

Back then, trade between the four founding

members—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and

Uruguay—was an engine of economic growth.

Then came traumatic devaluations and

economic stagnation. Total trade within the

block recently overhauled its previous peak.

But it is dwarfed by the growth of the

members' exports to the rest of the world

(see chart).

One reason for that is the surge in world

prices for South American soya, grains and

minerals. The second reason is that Mercosur

is drifting. It has failed to implement a pledge

to create a genuine customs union, with a

common external tariff and free trade within

the block. And it has allowed its rule book to

be riddled with exceptions.

The upshot is that barriers have multiplied. For example, Argentina's government

has tacitly backed the protestors who have blocked the main road bridge to Uruguay

for months on end, and has recently backed banana growers who object to the

import of cheaper Paraguayan fruit. Rather than use Mercosur's dispute-settlement

machinery, it has filed complaints against Brazil at the World Trade Organisation.

Paraguay has failed to clamp down on widespread smuggling of Chinese-made

electronic goods. And Brazil's partners object to the tax breaks given by its state

governments to attract investment.

The left-of-centre governments that are in charge (except in Paraguay) talk up

political and energy co-operation, though recently they have achieved relatively little

of either. They have also favoured widening the group, rather than its deepening into

a single market. Chile and Bolivia became associate members in the 1990s, entering

into free-trade agreements with Mercosur but not accepting its common external

tariff. Last year Mr Chávez's Venezuela was swiftly accepted as a full member, at the

urging of Argentina's president, Néstor Kirchner, and his Brazilian counterpart, Luiz

Inácio Lula da Silva. Now the left-wing presidents of Bolivia and Ecuador want their

countries to join too.

Marco Aurélio Garcia, Lula's foreign-policy adviser, claims that Mercosur has in fact

made “great progress” in integration, but that this is not yet visible because of the

intense social, political and economic change taking place in much of South America.

Others look at Mercosur and see merely irrelevance and disarray. “It's become just a

political block, not a trade block,” grumbles Marcos Jank, a trade specialist in São

Paulo.

Mr Chávez's absence from Asunción may, however, mark a turning point. He took

umbrage at a resolution passed by Brazil's Senate criticising his recent silencing of

the main opposition television channel. Brazil's Congress (like Paraguay's) has yet to

ratify Venezuela's entry to Mercosur, and after insults from Mr Chávez is unlikely to

do so soon. That leaves Venezuela in the oxymoronic situation of being a “full

member in process of accession”. Mr Chávez said this week that he would withdraw

Venezuela's application unless it was approved in three months. He seems interested

in Mercosur chiefly as a political platform. Free trade would expose the big

inefficiencies engendered by his statist economic policy.

Mercosur has plenty of other problems. They start with the big difference in size and

government policies among members. Under Mr Kirchner, Argentina's priority has

been to protect inefficient but labour-intensive industries as it recovers from socioeconomic collapse in 2001-02. Smaller Uruguay and Paraguay complain that the

group has done little for them.

Brazil has made periodic attempts to “relaunch” Mercosur. It is the main contributor

to a $100m development fund that is seen as a modest copy of the European Union's

regional funds. Its diplomats say they want fewer trade restrictions and, at last, a

common customs code (at present each country collects its own customs revenue,

and tariffs are levied on goods from outside the block each time they cross a

border). But in Asunción implementation of this was postponed yet again.

Mercosur's paralysis is beginning to exasperate businessmen. Though long

protectionist, Brazil's industrialists are nowadays keen to seek new markets. Paulo

Skaf, of São Paulo's industry federation, notes that although Brazil exports raw

materials to China, 70% of its manufactured exports are sold within the Americas.

He complains that Brazil is losing markets because the United States has struck

preferential trade deals in the region.

Brazil's decision to walk out of a recent meeting of the Doha round of world-trade

talks may owe more to pressures from allies than at home. If Doha does fail, some

diplomats see a chance of reviving stagnant talks on a trade agreement between

Mercosur and the EU (which this week held its first-ever summit with Brazil). That in

turn might push Mercosur to respect its own rules. Some Brazilians even talk of

trying to resume trade talks with the United States, broken off when negotiations for

a Free-Trade Area of the Americas collapsed in 2003.

Since Lula's re-election last October Brazil's foreign policy has seemed more

pragmatic and less driven by leftist ideology. Lula has not concealed his irritation

with Mr Chávez's antics. There is no sign yet that Brazil's president wants a clear

breach with his oil-rich friend and rival. But if Mr Chávez's brinkmanship backfires,

that might just be the best thing that has happened to Mercosur for years.

Copyright © 2007 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights reserved.