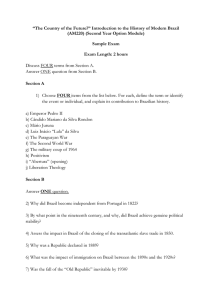

Document 15931202

advertisement

advanced search Search Welcome, Roger Bove Log Out My Profile Member Center About Us Help Member Edition 30 September 2006 Corporate Finance Economic Studies country reports productivity & performance Governance Information Technology Marketing Operations Organization Strategy Automotive Energy, Resources, Materials Financial Services Food & Agriculture Health Care High Tech Media & Entertainment Nonprofit Public Sector Retail Telecommunications Transportation go Research in Brief How Brazil can grow Social and economic policies can help the country overcome entrenched barriers to increased productivity. Heinz-Peter Elstrodt, Jorge A. Fergie, and Martha A. Laboissière 2006 Number 2 The lackluster performance of Brazil's economy over the past decade, when GDP per capita grew just 1.5 percent a year, has allowed the gap between developed economies such as the United States and Brazil to widen and provided an opportunity for fast-growing competitors such as China and India to gain ground (Exhibit 1). A study finds that the root cause of Brazil's weak growth is a relatively slow increase in labor productivity—the primary determinant of a nation's GDP per capita. Brazil's labor productivity was 23 percent of the US level in 1995 and fell to 21 percent in 2004. Your javascript is turned off. Javascript is required to view exhibits. To encourage a public debate among Brazil's leaders on how to boost economic development, we mapped the barriers to productivity growth in eight sectors—agriculture, automotive, food retailing, government, residential construction, retail banking, steel, and telecommunications—that together make up 46 percent of the country's economy.1 We found that about a third of Brazil's productivity gap with the United States is caused by two structural barriers. The first is the country's modest per capita income, which makes consumers favor lower-priced products and services. One illustration of the population's lower purchasing power: Brazil's automotive industry primarily produces small, inexpensive cars and relies on imports for higher-value-added vehicles. The second hurdle (labor is relatively cheaper than capital) discourages the use of machinery that would improve productivity. These structural limitations will fade if Brazil can achieve strong, sustained economic growth. But first the government must tackle the nonstructural barriers responsible for the remaining two-thirds of the productivity gap. All of these problems can be resolved through social and economic policies (Exhibit 2). Your javascript is turned off. Javascript is required to view exhibits. The most important barrier—responsible for some 45 percent of the nonstructural gap—is Brazil's huge informal economy, which represents about 40 percent of the gross national income.2 By avoiding taxes, ignoring quality and safety regulations, or infringing on copyrights, "gray-market" companies gain cost advantages that allow them to compete successfully against more efficient, law-abiding businesses. Honest companies lose profits and market share, and thus make less money to invest in technology and other productivity-enhancing measures.3 The second obstacle—macroeconomic instability—is reflected in the high degree of uncertainty among Brazilian executives about future exchange and interest rates and in the difficulties of forecasting demand for products and services. Executives are left with little choice but to focus on short-term financial management at the expense of growth and operating efficiency. Instability also discourages long-term investment (to automate operations, for instance), as companies and investors demand higher returns to compensate for macroeconomic risks. The result is that Brazil's interest rates are high—8 percent, compared with just 2.7 percent in the United States— and the market for long-term debt is virtually nonexistent. Regulations that limit productivity—such as labor and tax laws, price controls, product regulations, trade barriers, and subsidies—are equally problematic. Constraints on laying off workers (which add to employment costs) and restrictions on hiring temporary workers prevent businesses from adjusting their workforce to meet fluctuations in demand. Brazil's high sales tax (around 30 percent on a new car, compared with 7 percent in the United States) also hampers productivity growth, by reducing the demand for cars and reinforcing the industry's focus on producing low-value-added vehicles, for example. Inefficient public services are another hindrance. One-quarter of the population receives no secondary schooling; almost 12 percent of adults— some 15 million people—cannot read or write.4 In the agricultural sector, which employs some 20 percent of the workforce, this educational deficit impedes the adoption and effective use of modern seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and planting techniques. Modern farms in Brazil do use such techniques, but, even there, farm workers often lack the basic education needed to apply them most effectively. Finally, infrastructure limitations—including inadequate highways, ports, railroads, and power generation and storage facilities—cause problems, particularly in the agricultural sector. Up to 12 percent of all grain produced in Brazil spoils before reaching ports or consumers, for instance. The impact of these key barriers—informality, macroeconomic instability, regulation, the provision of public services, and the country's infrastructure— varies across sectors (Exhibit 3). Informality is the biggest obstacle to productivity growth in labor-intensive domestic sectors, while macroeconomic instability is the prevalent factor in capital-intensive export sectors. Your javascript is turned off. Javascript is required to view exhibits. Our experience suggests that once a country has identified its productivity barriers, it can tackle them through structural reforms and approaches tailored to each sector.5 Brazil's government should establish conditions for fair competition in domestic sectors and enhance international competitiveness of the economy as a whole to benefit its export businesses.6 About the Authors Heinz-Peter Elstrodt and Jorge Fergie are directors in McKinsey's São Paulo office, and Martha Laboissière is a consultant at the McKinsey Global Institute. Notes The study, "Brazilian economic program—Phase 1: Mapping barriers to growth in the Brazilian economy," was conducted in 2005 by McKinsey's São Paulo office in collaboration with the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). The project benefited from a previous McKinsey study on Brazilian productivity— see Martin N. Baily, Heinz-Peter Elstrodt, William Bebb Jones Jr., William W. Lewis, Vincent Palmade, Norbert Sack, and Eric Zitzewitz, "Will Brazil seize its future?" The McKinsey Quarterly, 1998 Number 3, pp. 74–83—and from similar MGI-sponsored studies in 16 countries. The methodology combines detailed analysis of labor productivity in different industries with a set of transverse analyses of the economy as a whole. 1 2 According to the World Bank. Joe Capp, Heinz-Peter Elstrodt, and William B. Jones Jr., "Reining in Brazil's informal economy," The McKinsey Quarterly, Web exclusive, January 2005. 3 Education Trends in Perspective: Analysis of the World Education Indicators, Unesco Institute for Statistics and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2005. 4 Didem Dincer Baser, Diana Farrell, and David E. Meen, "Turkey's quest for stable growth," The McKinsey Quarterly, 2003 special edition: Global directions, pp. 74–86. 5 Phase 2 of the study will examine specific measures that the government should take in these areas. 6 Site Map | Terms of Use | Updated: Privacy Policy | mckinsey.com Copyright © 1992-2006 McKinsey & Company, Inc.