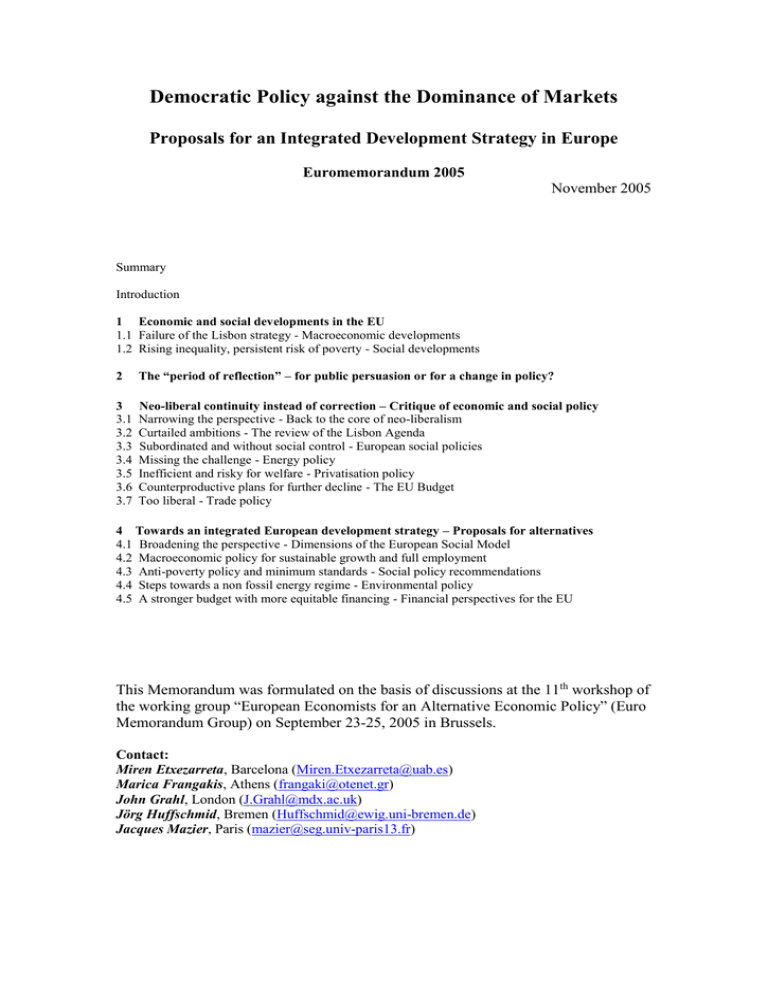

Democratic Policy against the Dominance of Markets Euromemorandum 2005

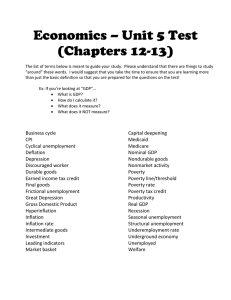

advertisement