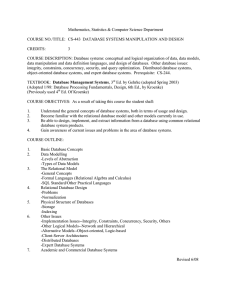

Comparing the Resource-Based and Relational Views: Knowledge Transfer and Spillover in Vertical Alliances

advertisement

Comparing the Resource-Based and Relational Views: Knowledge Transfer and Spillover in Vertical Alliances Strategic Management Journal, 29: 913–941 (2008) MA2M0102 吳佳蓁 Introduction Introduction compare resource-based and relational perspectives to examine competitive advantages suppliers acquire knowledge to forge new capabilities and attain performance improvements firms earn advantages by forging new capabilities through knowledge acquisition (Anand & Khanna, 2000; Dussauge, Garrette, & Mitchell, 2004; Dyer & Hatch, 2006; Grant, 1996; Hatch & Dyer, 2004; Kale, Singh, & Perlmutter, 2000; Khanna, Gulati, & Nohria, 1998; Mowery, Oxley, & Silverman 1996, 1998; Simonin, 1999, 2004; Spender, 1996; von Hippel, 1988) Literature review Literature review (1/8) Collective knowledge in buyer-supplier partnerships Hypothesis 1: redeploy-able performance knowledge acquisition relational performance Literature review (2/8) Joint knowledge acquisition and relational performance When suppliers develop knowledge acquisition efforts jointly with a given buyer, they are more likely to attain relational performance gains with that buyer. Anand and Khanna (2000) explain that alliance partners observe greater knowledge transfer effects over time, as their learning alliance becomes more efficient. Literature review (3/8) Joint knowledge acquisition and relational performance Hypothesis 2: redeploy-able performance Joint buyer supplier knowledge acquisition relational performance Literature review (4/8) Joint knowledge acquisition efforts and dyadspecific assets and capabilities Joint buyer-supplier knowledge acquisition efforts not only have a direct effect on a supplier’s relational performance (2), but also positively relate to a supplier’s investments(3a) in dyad-specific assets and capabilities, which in turn further enhance supplier relational performance (3b). Literature review (5/8) Joint knowledge acquisition efforts and dyadspecific assets and capabilities Hypothesis 3a: Joint buyer-supplier knowledge acquisition Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities Literature review (6/8) Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities, and relational performance Hypothesis 3b: redeploy-able performance Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities relational performance Literature review (7/8) Dyad-specific assets and capabilities and alliance governance mechanisms Hypothesis 4a: Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities Buyer-supplier relational governance mechanisms Literature review (8/8) Dyad-specific assets and capabilities and alliance governance mechanisms Hypothesis 4b: redeploy-able performance Buyer-supplier relational governance mechanisms relational performance Data and Methods Data and Methods (1/2) Research design and data collection 500 firms producing goods that involve machining, stamping, or cutting of basic material (e.g., sheet metal), and assembly of a component. Response rate was just above 50 percent, yielding 253 responses. Data and Methods (2/2) Measures five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents ‘not at all,’ and 5 ‘to a large degree.’ Control variables 1. Firm size 2. Importance of customer 3. Competitive pressure SEM Results Results (1/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy1 F1F5 = 0.185, t = 3.528, p < 0.001 redeploy-able performance (F5) knowledge acquisition (F1) F1F6 = -0.041, t = -0.748, p>0.1 relational performance (F6) Results (2/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy2 F2F5 = 0.028, t = 0.545, p > 0.1 redeploy-able performance (F5) Joint buyer supplier knowledge acquisition (F2) F2F6 = 0.110, t = 2.218, p < 0.001 relational performance (F6) Results (3/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy3a F2F3 = 0.194, t = 3.092, p < 0.001 Joint buyer-supplier knowledge acquisition (F2) Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities (F3) Results (4/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy3b F3F5 = -0.022, t = -0.412, p > 0.1 redeploy-able performance (F5) Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities (F3) F3F6 = 0.262, t = 4.498, p < 0.001 relational performance (F6) Results (5/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy4a F3F4 = 0.177, t = 2.859, p < 0.001 Supplier dyad-specific assets and capabilities (F3) Buyer-supplier relational governance mechanisms (F4) Results (6/9) Results of hypotheses tests- hy4b F4F5 = -0.035, t = -0.645, p > 0.1 redeploy-able performance (F5) Buyer-supplier relational governance mechanisms (F4) F4F6 = 0.209, t = 3.499, p < 0.001 relational performance (F6) Results (7/9) Results of hypotheses tests 2 △X △df p-value Hy1 (supported) 18.972 1 < 0.001 Hy2 (NOT supported) 1.586 1 > 0.100 Hy3a (supported) 14.228 1 < 0.001 Hy3b (supported) 22.265 1 < 0.005 Hy4b (supported) 15.962 1 < 0.001 > 3.85 Results (8/9) Results of control variables p > 0.10 Firm size p > 0.10 redeploy-able performance relational performance Importance of customer p > 0.10 Competitive pressure p < 0.001 p < 0.01 p < 0.01 Results (9/9) What the results mean importance of buyer-supplier knowledge transfer alliances → relational performance alliances → assets and capabilities assets and capabilities → relational performance assets and capabilities → governance mechanism governance mechanism → relational performance Discussion & Conclusion Discussion and conclusion (1/3) tacit, team-based capabilities attain competitive advantages acquired capabilities are redeployable, rendering improvements on a supplier’s performance Discussion and conclusion (2/3) 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Y X X+ Discussion and conclusion (3/3) Limitations and directions for future research This study is limited to an analysis of suppliers’ asset investments and relational mechanisms; it thus may have missed the effects of buyers’ complementary asset investments. References References (1/3) Anand BN, Khanna T. 2000. Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strategic Management Journal March Special Issue 21: 295–315. Dussauge P, Garrette B, Mitchell W. 2004. Asymmetric performance: the market share impact of scale and link alliances in the global auto industry. Strategic Management Journal 25(7): 701–711. Dyer JH, Hatch NW. 2006. Relation-specific capabilities and barriers to knowledge transfers: creating advantage through network relationships. Strategic Management Journal 27(5): 701–719. Grant R. 1996. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal Winter Special Issue 17: 109–122. Hatch NW, Dyer JH. 2004. Human capital and learning as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic management journal 25(12): 1155–1178. References (2/3) Kale P, Singh H, Perlmutter H. 2000. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal March Special Issue 31: 217–237. Mowery DC, Oxley JE, Silverman BS. 1996. Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strategic Management Journal, Winter Special Issue 17: 77–91. Mowery DC, Oxley JE, Silverman BS. 1998. Technological overlap and interfirm cooperation: implications for the resource-based view of the firm. Research Policy 27(5): 507–523. Simonin BL. 1999. Ambiguity and the process of knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal 20(7): 595– 623. Simonin BL. 2004. An empirical investigation of the processes of knowledge transfer in international strategic alliances. Journal of International Business Studies 35(5): 407–427. References (3/3) Spender J-C. 1996. Competitive advantage from tacit knowledge? Unpacking the concept and its strategic implications. In Organizational learning and competitive advantage, Moingeon B, Edmondson A (eds). Sage: Newbury Park, CA; 56–73. Von Hippel E. 1988. The Sources of Innovation. Oxford University Press: New York. Thanks for your attention.