ANNEX C SECOND WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS BY THE PARTIES

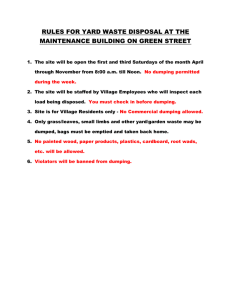

advertisement