ANNEX A FIRST WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS BY THE PARTIES

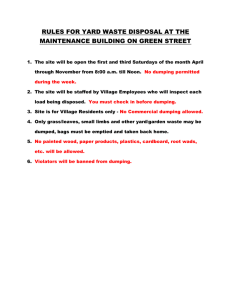

advertisement