Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes Collection of contributions received

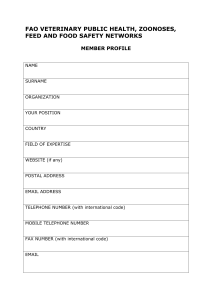

advertisement

Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes Collection of contributions received Discussion from the 27 November to the 18 December 2013 These discussions are led by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the World Food Programme (WFP) and facilitated by the Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN Forum) www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 2 Table of contents Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction to the Topic ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Contributions Received........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Pat Heslop-Harrison, University of Leicester, United Kingdom .......................................................... 5 2. Gunasingham Mikunthan, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka...................................................................... 5 3.Krishna Kaphle, Tribhuvan University, Nepal ............................................................................................. 5 4. Hari Kala Kandel, Canada .................................................................................................................................... 6 5. Eileen Omosa, UoA and CeBRNA, Canada ..................................................................................................... 6 6. Jean Max St Fleur, WFP, Haiti............................................................................................................................ 8 7. Susanne Kayser-Schillegger, Marshall Islands ........................................................................................... 8 8. Heiko Recktenwald, Germany ........................................................................................................................... 8 9. Erin McCandless, consultant; Interpeace, United States of America ................................................. 8 10. Ruby Khan, FAO Somalia, Kenya .................................................................................................................... 8 11. Laetitia van Haren World Watch Food Tank/ Synergeis for Biological and Cultural Diversity/NGOForum for Health/Mothers Legacy Project, France ........................................................ 9 12. Hector Morales GIZ, Colombia ...................................................................................................................... 10 13. Kenneth Senkosi, Forum for Sustainable Agriculture in Africa, Uganda..................................... 10 14. Henk-Jan Brinkman, United Nations, United States of America ........................................................... 11 15. Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval and Diane Hendrick, conveners of the discussion .................................. 11 16. George Kent, University of Hawai’i, United States of America ........................................................ 13 17. Florence Egal, Italy ............................................................................................................................................ 14 18. Petr Skrypchuk, National University of Water Management and Nature, Ukraine ................ 14 19. Stephanie Gill, Tearfund, United Kingdom .............................................................................................. 15 20. Noura Fatchima Djibrilla, ACFM Niger, Niger ........................................................................................ 16 21. Karim Hussein, IFAD, Italy ............................................................................................................................. 16 22. European Commission, European Union ................................................................................................. 19 23. Manuel Castrillo, Proyecto Camino Verde, Costa Rica ........................................................................ 20 24. Adam Kabir Dickinson, IAFN-RIFA, Costa Rica ...................................................................................... 22 25. Alexandra Trzeciak-and Duval and Diane Hendrick, conveners of the discussion ................ 23 www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 3 Introduction to the Topic Dear Forum Members, In 2010 the State of Food Insecurity in the World (SOFI) report estimated that there were over 160 million undernourished people in protracted crisis situations. The proportion of undernourished people in protracted crisis situations is about three times as high as in other developing contexts – and the longer the crisis, the worse the food security outcomes. The longer we delay concrete action, the larger the problem, as has been demonstrated in Africa. In 1990, forty-two percent of the 12 countries facing food crises in Africa had been in crisis for eight or more of the previous ten years; by 2010, the total number of countries experiencing one or more food crises had doubled, of which seventy-nine percent had been in crisis for a prolonged period. The Committee on World Food Security (CFS) launched a consultative process to elaborate an Agenda for Action for Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises, to be submitted to CFS 41 in October 2014 for endorsement. This e-discussion is intended to contribute to the drafting of the Agenda for Action by involving those who are closest to protracted crisis situations. Our discussion will explore issues such as, (1) the linkages between food insecurity and fragility, including through fragility assessments; (2) the role that food security and nutrition can play in fragile and conflict-affected states, particularly in the specific context of the New Deal Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals; (3) the respective roles of governments, local constituencies, civil society and relief and development actors, and (4) ways to ensure accountability and relevance through broad inclusion, including of vulnerable and marginalized groups, in decision-making, planning and monitoring. This e-discussion seeks your experience and views to shape a practical, actionable Agenda for CFS adoption, which will help guide implementation on the ground. In the ongoing elaboration of the Agenda for Action, the complex interrelationship between conflict and food insecurity is recognised – peacebuilding interventions at various levels are understood to be crucial to emergence from protracted crisis, and to ensure an enabling environment for viable food systems to underpin food security and nutrition. In addition, food security programming has potential spill-over effects and opportunities that are wider than addressing hunger and malnutrition in affected populations; improved food security and nutrition can contribute to sustainable peace-building through improved social cohesion, capacities, trust, legitimacy, amongst others. This is, however, complicated by the risk of agricultural and food security related assets also potentially being conflict drivers and/or threat multipliers. Countries and contexts in protracted crises are often accompanied by poor governance, weak capacities and a lack of basic systems. Be it cause or effect, where governments are unable to meet public needs and provide essential services, the potential for dissent is high. Where participatory, inclusive approaches are applied, the potential for strengthening the technical and logistical capacities www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 4 of government and even their legitimacy is considerable. Particular attention needs to be given to marginalized and vulnerable groups. The effectiveness and desirability of women’s involvement in resolving and recovering from conflict, and in creating sustainable peace, has long been recognized1 . The essential role of women in both national and household food security in post-conflict settings requires that certain barriers to their involvement be removed – such as the violence and fear of violence that restricts their access to fields and markets and the restrictions on property rights that mean they are unable to inherit land and obtain credit on the basis of it. Mainstreaming food security into peacebuilding will require its integration from the initial point of conflict analysis onwards, and must address the power dimension, from household, to community to state level. This implies more than conflict sensitive development. Creating enabling environments for resilient communities and societies to emerge will require a long-term, adaptive engagement and necessitate new approaches to funding in such settings. We invite strong participation in the e-discussion around the following questions to ensure a relevant, effective Agenda for Action. Examples of successful strategies, programmes and tools, would be particularly helpful to all concerned to illustrate what works and might be adapted for use elsewhere. 1. In your experience, what are the key programmes and processes through which to mainstream food security into peacebuilding processes and get appropriate buy-in from all those involved? 2. What role can food security and nutrition play in fragile and conflict-affected states, particularly in the specific context of the New Deal Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals, and how best can food security and nutrition considerations be integrated into New Deal priorities? 3. Who should be held accountable for progress on food security in protracted crisis contexts and how can we measure progress towards specific targets? Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval Diane Hendrick 1 UN Security Council Resolution 1325 passed in 2000 recognised the undervalued contributions and underutilized potential of women in conflict prevention, peacekeeping, conflict resolution and peacebuilding. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 5 Contributions Received 1. Pat Heslop-Harrison, University of Leicester, United Kingdom "Countries and contexts in protracted crises are often accompanied by poor governance, weak capacities and a lack of basic systems." How about adding "or rapid population growth" to this sentence? Many countries have 'basic systems' and 'capacities' which in absolute terms have improved enormously in this century, but relative to population have declined. For example, will anybody be evaluating formally whether the tragic events in the Philippines would have had a different outcome with a population less than 80 million (2000) compared to 100 million now (2013)? Has infrastructure and planning improved in this time but been overwhelmed by extra pressures from population growth? 2. Gunasingham Mikunthan, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka The programmes on food security to a peace-building process should be developed to the participation of all families affected and there should be consideration to get the reasonable share to feed the family members initially through access to relief materials but later to support them to produce their minimal food. These vulnerable groups have to be taken care their family wellbeing otherwise they could be utilized by anyone. Those families could be grouped and the task should be given to the members by providing starter materials. They could be educated/trained then and there and let them come out this tragedy of shortage of food materials. As I mentioned, people under the conflict areas are vulnerable to the availability of food, nutrient supplement and income generation. This could be considered seriously and programs should be developed to admire them and to support them to come out possible solutions. Solutions already taken in a different place may not work rather, decisions should be taken with the concern of the active members in the village. Appropriate representation would help to design most appropriate mechanism to do the changes All state and non state sectors are responsible for the sufferings and all stakeholder is into your decision making but the members should get a wonderful exposure - collapse | read on a separate page 3.Krishna Kaphle, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Dear Moderator, Thank You for the initiative and role in conducting such an important issue for discussion. The Topic "Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes", taking place on the Community of Practice on Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises is crucial in this juncture of Human History. With population on rise and unequally distributed in terms of available resources and advancement of science and technology.Not to mention about Nature that is fighting back for all www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 6 the atrocities committed on it, human ignorance and greed is creating conflict in name of ethnicity, religion, region, political ideology and share over natural resources. All these are only contributing to Human misery with resources and food becoming scare and streamed to fulfill demands of rich and booming middle class in highly populated areas. The growing population of the planet that is bound to rise for another fifty years is a severe global concern. Though, negative population growth in some countries may be positive news but now with relaxed birth control policy in China, uncontrolled growth in many developing and underdeveloped nations, rise in ethnic politics (incentives to bear children) is bound to delay balance of global population. The challenge to feed growing mouths by ensuring that the delicate ecosystem remain preserved no small task in itself. The world has to be free from hunger and “the broad zero hunger vision” as articulated by the United Nations Secretary-General will be hugely boosted by the involvement of everyone at ground level and even virtually. Production of food by small cultivators in developing countries has a critical role to play in ending world hunger and they need protection and promotion in all fronts even with the revision of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on agricultural price support if necessary. The volatile price fluctuation, agent governed markets, lack of timely inputs, climate change resulted non-supporting weather, shifting generation of youths to urban settings and many more factors are discouraging to farming activity. In the international scale, there are subsidies and protection termed as “Green Box subsidies” in developed countries, large scale mechanized farming, liberal policy in the adoption of genetically modified organisms (GMO) is supporting agriculture sector. In developing and underdeveloped countries where majority population are engaged in agriculture there is lack of comparable levels of support making cultivation by small producers in developing countries even less viable and uncompetitive. 4. Hari Kala Kandel, Canada Health-Food Security and Conflict all go hand in hand. Managing, mitigating resources, equity, gender role reversal are some issues to address them. The misconception that developed nations are free from hunger is far from truth. Local food culture development, healthy eating initiatives over spending on health should be envisioned from early school education. Training child care profesonals, health care aides and others to realize the value of good eating and adopting them should be promoted, evaluated and encouraged. Food waste, the worst of all evils, should find top spot in the list of vices, if we are to feed the hungry billions. Filled bellys and busy brains will find something else to do rather than go and snatch someone else's resources. History, that have praized mideveal era "heros" should again be rewritten and taught critically for exposing the greed, conspiricy and plights those invasions/wars cost. 5. Eileen Omosa, UoA and CeBRNA, Canada Conflict causes food insecurity and food insecurity causes conflict. What do you as a development worker say when your conversation with a middle-aged man on their involvement in raids and violent conflicts receives this response “I worked within the only two options available, either sit at home and watch my children die from hunger or go out and get them food through whatever means.” The quick response will be teas for two reasons: one, your heart has been touched, and two to get a quiet moment to reflect on your `office’ prepared document on how to manage an on-going conflict. My contributions to this discussion will be done in stages and draw from my field- experiences working in the natural resources sector for over 10 years: www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 7 In relation to approach, I suggest the need to review our basis for development plans aimed at helping people involved in conflicts (natural resources related in this case) get out of the situation i.e. are the plans context-specific or one size fits all? Drawing on my work with communities in the Karamoja Cluster (neighbouring communities in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and SSudan), I got to learn of the need for a good grasp of issues/reality on the ground. These include the existing methods used by local people to share scarce natural resources (pastures and water in this case), analysis of existing policy (Local, State and international) on the role of local communities in the management of natural resources and sharing of accrued benefits. The objective of such a process will be to use the `reality’ on the ground as the basis on which to develop guidelines to be used by development agencies working with particular communities on the management of natural resources-based conflicts with the objective of attaining food security. On methods for sharing the scarce natural resources e.g. pastures and water for livestock which in turn provide for food and cash security: There is need to accept that some of the on-going conflicts have been there for generations, what has changed is the frequency and magnitude of casualties, partly explained by access and use of automatic weaponry. Talking to people from the different communities involved in the conflict, one will come to a realization that these communities have always had wellunderstood structures/organizations to guide access and the sharing of natural resources. Some of the arrangements involved the formation of alliances to share available resources available in different locations or lands held by different communities, and sometimes alliances to forcefully access required resources. Most of these traditionally managed arrangements have changed with changes in diversity and size of populations, climate change and shifts in seasons and location of resources, and the introduction or effecting of arbitrary borders that end up restricting the seasonal movement of people and livestock. Approach: Such a situation would call for the formation or strengthening of local cross-border (community, regional, national, international) arrangements for resource sharing. Experience taught me that because local people know their history, especially in terms of who is a `seasonal’ friend, a long-term friend and a long term enemy, they are best placed to develop cross-border networking/collaboration strategies. They could do with outside facilitation in the mobilization of stakeholders and information sharing sessions. The successful formation of cross-border networks/collaboration for sharing natural resources is a long-term process involving detailed consultations within and across communities. Within communities and households, consultations would call for an understanding of the nature of assets and decision-making. For example the perception of an outsider might be that conflicts are started by men because they are the ones who participate in actual fights. However, interactions and discussions with community members as men, women, elders and children could reveal that men from particular communities cannot participate in a violent conflict without blessings from women or elders. A seemingly minor but very critical factor in efforts put towards the transformation of conflicts and peacebuilding. My suggestion: The need for gender and stakeholder analysis to identity the bundle of rights held by different people to a resource, and existing modalities for access to the resource. Analysis to identity existing resources/assets held by the households, with the objective of facilitating them to diversify their livelihood strategies either by adding value to their local resources or moving away from dependency on natural resources. The need to share information and lobby concerned governments to separate reality from politics i.e. respect the cross-border movements as traditional ways of accessing seasonal natural resources and not a sign of `non-committed citizens’. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 8 The picture of a well-managed conflict: Local people are able to visit their farms, cultivate and harvest food crops without fear of attacks or losing their crop to thieves. Local people travel to and from markets without having to surrender their merchandize or cash to armed attackers. Families in need are able to reach to their social relations and networks to receive food items, etc. 6. Jean Max St Fleur, WFP, Haiti Une formation sur la problématique de la sécurité alimentaire dans une perspective de construction de processus de paix doit cibler ces milliers de femmes du secteur économique informel, dans les pays en voie de développement, qui défrichent les terres agricoles, génèrent de l’argent pour nourrir leurs foyers, éduquer leurs enfants et soutenir leurs communautés. 7. Susanne Kayser-Schillegger, Marshall Islands Having lived for more than 27 years in Africa with ample opportunity to watch and experience food shortages as well as food distribution. Food distribution does not work, it is more often than not stolen and does not reach people. I have witnessed tinned food - a gift from Denmark - being sold in an Arabic Souk while it was given to people in Sudan! We have found that the best way to ensure that people get food is to give them simple tools and good seeds, dig a well or two and the people will proudly look after themselves since the fields are their own and the production is in their hands. Do not make people professional beggars relying on food support that may never arrive, give them dignity by giving them tools, water and seeds. Abstain from silly big farming projects, engage in grassroots projects that reach the people directly and much can be achieved. 8. Heiko Recktenwald, Germany Well, what a wonderful question 1! The distribution of food must be fair. You can’t buy peace directly but maybe in this indirect way. You have some force. 9. Erin McCandless, consultant; Interpeace, United States of America I'm sure you know of the attached report, as FAO participated. But just in case! http://www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises/sites/protractedcrises/files/resources/Peace%20dividends%20and%20beyond.pdf 10. Ruby Khan, FAO Somalia, Kenya Food security, nutrition and livelihoods can serve as a confidence building platform where communities negotiate on an issue that is of mutual importance. It can serve as areas to negotiate and agree particularly on nutrition for children and vulnerable, poor households, women, elderly, where most groups find common goals. In addition, negotiating the responsible management of communal resources (water, land, forests, etc.) can also serve as a way to reach agreement where other issues are too difficult to agree on. Additonally, working on livelihoods through a rights based approach, ie providing access to marginalized groups, minorities, etc. can increase buy in not only in the peace process but also in www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 9 support of political participation within the mainstream, and facilitate the discussions on other more difficult issues. Fringe groups can be brought to the table if basic issues such as food security and increasing self-sufficiency in the ability for communities to provide for themselves will be supported. This reduces the idea of dependency on external assistance which becomes a grievance in the narrative of certain political groups. The improvement of state-society contract (as mentioned previously) cannot be underestimated as a precursor or underlying peacebuilding processes. Poverty, lack of access to basic services and general issues of basic dependence on the state or external actors should be addressed in a comprehensive way by development actors to increase the impact of the provision of basic services to meaningfully contribute to peacebuilding processes. 11. Laetitia van Haren World Watch Food Tank/ Synergeis for Biological and Cultural Diversity/NGOForum for Health/Mothers Legacy Project, France Ensure safe access to the market and no "ponctionnement", that is, remove barrriers (whether they exist in the form of road blocks or individuals with guns holding up assers-by) on the road towards the market where those bringing produce to sell have to give some of their produce to one "access controller" after another, where police, militia, local administrors or plain thugs serve themselves unlawfully and sometimes even violently. Ensure public safety in general so that all people, including women and children, can go to the fields or go wherever they want or need close or far, for safe pedestrian mobility is the condition sine qua non for re-establishing food security, whether by farming one's own plot, working on someone else's land or earning one's livelihood in another manner. Ensure that young people are also included both in the pacification and in the reconstruction process, also young, poorly or uneducated farmers, and even young slum dwellers. Give them some training if necessary, but involve them, because it is the repressed, unemployed and futureless youth that is the best fodder for cannons and corrupt politicians seeking to create a climate of terror. Ensure the creation of re-opening in a fair manner of producers' ( and other) cooperatives. If the cooperatives have been corrupted by power shifts caused or produced by the conflict, unfortunately most often towards more inequality, then either work towards correcting the existing cooperatives or, if this is totally impossible, start up new ones. I would always prefer cleaning up existing frameworks and institutions, though. The rebuilding of fairly functioning cooperatives should go together with honest weighing and paying processes, whether this means price control or the opposite, depending on the situation, Get every family or household to grow food in some way, that is, promote urban farming and horticulture in composting bags, and promote actually also eating those vegetables by teaching how to use them in the mainstream diet. I say this because I have seen so much vegetable farming only started for selling to the elites, foreign or not, whereas food security and indirectly general socioeconomic security would be enhanced if, when market demand drops, the family could reduce its expenses by consuming more of their own produce (not to mention the nutritional benefit of course of eating more veggies). This helps urban poor families to supplement their income and their food intake. However, for peace through food security we must be aware that food is not enough, there must be an inbuilt margin of non-survival consumption or those who hold the power, from the lowest level in the www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 10 household to the highest levels of government, will simply prefer to starve (with some poetic exxaggeration!) those who are under their control than give up their own consumption of whatever is power and status enhancing. Food security, peace and stability are seriously thwarted by the demand for drugs, alcohool, sex, violence (yes violence is not only a means to an end it also acts as a drug in combination with other drugs) which so appeal to young and mature men, especially if "normal" satisfaction perpectives for the present and the future are out of reach. So we won't escape the never ending challenge to diminish the attraction and/or availability of those powerful but destructive means to feel good, strong, or simply to forget...Chaos serves access to those drugs, so peace through food security has a truly strong adversary! 12. Hector Morales GIZ, Colombia We have to made a step forward to pass the stage of food security to sustainable effective food production projects. The underdeveloped world needs better research patrons to make added value to their products. That includes agro industrial projects. Peace building should take into account the value of research and knowledge to include into small communities. Applied research methods can make better life to all. We have to take into account that subsidarie governmental programms can some times be counterproductuve, due to the fact that people can not make a living on their own. DO no harm theories and sustantable approaches are good ways to develope progress and trust. Here are some projects of peace building in Colombia : www.cercapaz.org 13. Kenneth Senkosi, Forum for Sustainable Agriculture in Africa, Uganda Dear Moderators, Allow me share views from an African context. As regards, the issue of accountability towards food security in protracted crisis situations, I strongly believe that its the responsibility of both and/or more parties behind the crisis/conflict to ensure that the population whose rights both claim to be fighting to defend has access to food even if it is aid supplies. Its very sadenning when we watch news that even aid workers were denied access to a given population, the immediate result of which is always enhanced food and nutrition insecurity. Additionally, in situations where one party claims to be fighting a bad government, food security would not be greatly compromised if the conflicting parties would avoid the temptation of turning their guns on the innocent population they both claim to be fighting for. This would give chance for the population to continue with their subsistance farming activities. In terms of monitoring progress, I suppose one of the indicators would be the level of committment (both verbal and/or policy statements) by both leaderships behind the conflict. This would give a window for international and/or local civil society to followup and probe either parties strives/efforts towards a food secure population in situations of political instability. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 11 Regards, Kenneth Senkosi 14. Henk-Jan Brinkman, United Nations, United States of America Dear all, It is important to mainstream food security into peacebuilding but I would argue that the reverse is equally or even more important given the size of the programmes. Cullen Hendrix and I have higlighted int he attached ways to do that. To quote: "FAO-WFP (2010) identifies five characteristics of protracted crises: duration or longevity; conflict; weak governance or public administration; unsustainable livelihood systems and poor food security outcomes; and breakdown of local institutions. These characteristics are quite common in the Sahel. Food security interventions through the integration of a peacebuilding approach could address these symptoms of a protracted crisis through the generation of peace dividends, the reduction of conflict drivers, the enhancement of social cohesion, and the building of legitimacy and capacity of governments." Best regards, Henk-Jan 15. Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval and Diane Hendrick, conveners of the discussion Many thanks to all for the thoughtful opening comments for our e-discussion on mainstreaming food security into peacebuilding processes. A number of ideas to nourish the Agenda for Action have emerged. They will provide inspiration for many more comments expected in the days and weeks to come. Let’s recall the three questions posed to frame the e-discussion and summarise what we have learned from comments received so far. 1. In your experience, what are the key programmes and processes through which to mainstream food security into peacebuilding processes and get appropriate buy-in from all those involved? We have the beginnings of a set of principles/criteria that must apply to any programme or process to mainstream food security into peacebuilding: Be context specific and in touch with realities on the ground. (Eileen Omosa, UoA & CeBRNA, Canada) Develop guidelines for development actors based on the analysis of the role of local communities and their traditional arrangements for managing and sharing scarce resources. These must include gender and stakeholder analysis – with their participation -- to identify the bundle of rights held by different people to a resource and modalities for access to it. (Eileen Omosa; Hari Kala Kandel, Canada) www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 12 Together with local communities, facilitate the adaptation of traditional arrangements to changes in the environment, e.g. demographic, trans-border, climatic and other impacts. (Pat Heslop-Harrison, University of Leicester, UK; Krishna Kaphle, Tribhuvan University, Nepal) Target and work with women in the informal sector whose economic support is vital to their families and communities and who, together with elders, often have a major role in influencing conflict situations. (Jean Max Fleur, WFP, Haiti; Eileen Omosa) Ensure secure conditions of public safety that enable farmers to access their land for cultivation and harvest, people to access markets to buy and sell production, and people to access their families and social networks to help one another. (Eileen Omosa, Laetitia van Haren, World Watch Food Tank/Synergies for Biological and Cultural ) Aim for food security and enhancing the ability of groups to provide for themselves in a sustainable way without dependency on external assistance. (Gunasingham Mikunthan, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka; Hector Morales, GIZ, Colombia; Laetitia van Haren, Ruby Khan, FAO Somalia, Kenya, Susanne Kayser-Schilleger, Marshall Islands; Krishna Kaphle) 2. What role can food security and nutrition play in fragile and conflict-affected states, particularly in the specific context of the New Deal Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals, and how best can food security and nutrition considerations be integrated into New Deal priorities? Food security, nutrition and livelihoods can serve as a confidence-building platform where communities negotiate on the basis of an issue of mutual importance. Often agreement can be reached around shared goals like nutrition for children and vulnerable, poor households, women and the elderly. (Ruby Khan, FAO Somalia, Kenya; Heiko Recktenwald, Germany) Negotiating the responsible management of communal resources (water, land, forests, etc.) can serve as an entry point to facilitate agreement on other issues that are too difficult to tackle initially. (Ruby Khan) Working on livelihoods through a rights-based approach, i.e. providing access to marginalised groups, minorities, etc., can increase buy-in, not only into the peace process but also in support of political participation. (Ruby Khan) 3. Who should be held accountable for progress on food security in protracted crisis contexts and how can we measure progress towards specific targets? The improvement of the state-society social contract for the provision of basic services must underpin any peacebuilding process. Poverty, lack of access to basic services and general issues of basic independence are issues caused and exacerbated by poor governance. Thus governing authorities are accountable. (Gunasingham Mikunthan, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka; Krishna Kaphle, Tribhuvan University, Nepal) But it is also the responsibility of all the parties behind the conflict or crisis to ensure that the population whose rights they claim to defend has access to food. (Kenneth Senkosi, Forum for Sustainable Agriculture in Africa, Uganda) One of the monitoring indicators would be the level of commitment, through both verbal or policy statements by both or all leaderships behind the conflict, allowing civil society and international actors to follow-up and probe the conflicting parties’ efforts to ensure a food secure population in situations of political instability. (Kenneth Senkosi, Forum for Sustainable Agriculture in Africa, Uganda) To keep the discussion going, we would like to probe some of these ideas further. 1) Although getting communities emerging from conflict to work together on superordinate goals -- in this case something like nutrition for children -- as a way of re-building relationships is a staple of www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 13 conflict transformation approaches, in complex conflict settings a simple transfer to other areas of social interaction will not be straightforward. Sometimes natural resource access and use are merely another arena in which to play out conflict stemming from elsewhere and addressing these intergroup conflicts at another point could result in better cross-community problem solving around food access and distribution. Any intervention within a complex system will have indirect as well as direct effects, some intended, some not. This provides opportunities but should make us wary of linear assumptions. 2) The discussions around interventions at community level, intended to have an impact on food security and peacebuilding outcomes, are very relevant as much of the conflict around natural resources occurs at this level. However, the peacebuilding and statebuilding goals, and the way in which the international system approaches them, are very state-focused. What are the necessary approaches to relate these community level processes to the international state-level interventions? There is obviously much good reflection and thinking going on out there, and much to build on as we continue this discussion. We have heard voices from civil society, academia, agencies and individual practitioners. What is surprising is that we haven’t heard from key stakeholder groups we would have expected to -- and we know they have important perspectives and insights. We are especially thinking about those involved in and around New Deal processes, particularly at country level, given the importance of this initiative and its link to protracted crisis situations and fragile contexts. This conversation will not be complete without them. This e-discussion will continue over the holiday period until 17 January 2014 so there is still plenty of time to weigh in! 16. George Kent, University of Hawai’i, United States of America Greetings – I appreciate this discussion on Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes. However, so far little attention has been given to the role of the human right to adequate food, and international humanitarian assistance in that context. Most discussions of human rights are about the obligations of national governments in relation to the human rights of people under their jurisdiction. However, in protracted crises resulting from armed conflict, economic collapse, or geophysical hazards such as floods and earthquakes, national governments cannot, or perhaps will not, carry out their obligations relating to food security and nutrition. In recent years there has been increasing recognition of the importance of extraterritorial obligations. This can be viewed as implying an obligation of the international community, taken as a whole, to provide humanitarian assistance in crisis situations. However, the donor countries have not recognized any concrete obligation to provide international humanitarian assistance. This is especially clear in the way the Responsibility to Protect doctrine has been interpreted. The language of responsibility suggests that the countries that do the intervening have specific obligations to intervene when necessary for humanitarian purposes, but they really use it to assert their right to intervene. The legal obligation to provide assistance to people in need under domestic law is discussed in terms of the duty to rescue. However, under international law, there is a curious change in perspective. The discussion is mainly about the rights of the donors to deliver assistance without interference. The www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 14 argument says needy people have a right to receive assistance if other people offer to provide it. It does not say that the needy have a right to receive certain kinds of assistance, and therefore others have an obligation to provide it. The main concern appears to be with the rights of those who provide the assistance, not the rights of those who need it. The international community has turned the responsibility to protect, understood as an obligation, into a right to intervene—if and when it wishes. Countries that intervene in other countries on humanitarian grounds should not be free to choose who and when they help. Stopping genocide or starvation should not be optional. There should be recognition of obligations, and not only rights, on the part of those who would intervene. If the powerful countries are going to claim a right to assist under some conditions, they should also have an obligation to assist under some conditions. Despite their talk about responsibility, the donor countries don't really acknowledge any sort of obligation to provide humanitarian assistance if it does not suit them. The human right to adequate food should be recognized internationally as well as within countries. Protracted crises are not merely local; they are also problems of the world, and should be viewed as matters of responsibility for the world as a whole. Aloha, George Kent 17. Florence Egal, Italy Dear Alexandra and Diane, I am sure you are aware of the background document Linking conflict and development: a challenge for the MDG process prepared by a multi-disciplinary FAO team upon request of FAO's Director General for the CFS 31st session special event Impact of Conflicts and Governance on Food Security and FAO’s Role and Adaptation for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/meeting/009/j5292e.pdf. Another document which could provide some relevant insights would be Child Nutrition and Food Security during armed conflicts http://www.fao.org/docrep/W5849T/w5849t07.htm#xchild%20nutrition%20and%20food%20secu rity%20during%20armed%20conflicts Sorry about the formatting, I'm not very good at this and I do not seem to have much choice. Season's greetings everybody. Florence 18. Petr Skrypchuk, National University of Water Management and Nature, Ukraine [Original contribution in Russian] www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 15 На вопрос .... По вашему опыту, каковы основные программы и процессы, посредством которых можно было бы выдвинуть на передний план проблему продовольственной безопасности в процессе миростроительства и получить соответствующий вклад со стороны всех участников? Считаю целесообразным роазработать методологический подход с тандартизации на уровне ISO / Технического Комитета 207 о глобальных подходах (Директиве на уровне ЕС) к возрастанию рисков антропогенного загрязнения и продовольственной безопасности. Тоесть куда двигаться, что добровольная сертификация а что обязательная [English translation] Respond to the question.... From your experience, what are the main programs and processes that will bring to the forefront the problem of food security during peacebuilding process and obtain an appropriate contribution from all of the participants? I consider it expedient to develop a methodological standardisation policy at the level of ISO / Technical Committee 207 on global approaches (EU Directive) to the increased risks of anthropogenic pollution and food safety. I.e. where to go to What a free-will certification is, and what a mandatory certification is 19. Stephanie Gill, Tearfund, United Kingdom Dear Alexandra and Diane Please allow me to introduce myself - I am the Policy Officer for the Sahel for Tearfund - my focus countries being Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Chad. Tearfund works through local partners and my role is to both help partners with in-country advocacy and to advocate on their behalf. After a long scoping exercise we are looking to advocate on issues of access to and sustainable use of natural resources- and the links of this with conflict. Over the next two months I shall be travelling to Chad, Niger and Mali to meet with partners, finalise in-country advocacy plans and key messages. I am emailing because I am sure that our partners would be keen to contribute their thoughts and experiences to the Agenda for Action. I was emailing to ask your guidance on any key inputs that I could gather from partners could during my visits to them, as I know these dates do not fit exactly with the e-discussions. For your information I attach a partner briefing of specific partner work on these issues. Please let me know if there is anything from our work, that you feel could be a useful contribution, or would like further information on. Thank you and I look forward to hearing from you. Best wishes Stephanie www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 16 Stephanie Gill Policy Officer - Sahel West & Central Africa Team Tearfund 20. Noura Fatchima Djibrilla, ACFM Niger, Niger [English translation] Conflicts can only generate food insecurity, especially as because the able-bodied that have to produce for other members of society are mobilized to the front. It is only when peace comes back that productive and development activities can start again. For countries like ours, ie LDC (Least Developed Countries), where in most cases, the primary sector represents between 10 and 80 percent, I think we should review the Maputo 10 percent as it has become obsolete and we need to put at least 25% of national budgets and even more in agriculture for results to be significant. We therefore invite our leaders to invest more in order to overcome the problem of food insecurity, intensifying irrigated land, off-season farming, improving water sources. [Original contribution in French] Les conflits ne peuvent qu'entrainer l'insécurité alimentaire, d'autant plus que ce sont les bras valides qui doivent produire pour les autres membres de la société qui sont mobilisés pou le front. C'est quand la paix revient seulement que les activités de production et de tout développement reprennent. Pour nos genres de pays, c'est à dire les PMA, ou dans la majorité des cas, le secteurs primaire constitue entre 70 et 80 pour cent, je pense qu'on doit revoir les 10 pour cent de Maputo, car c'est devenu obsolète, il faut mettre au moins 25 pour cent des budgets nationaux, et même plus dans l'agriculture, pour que le résultat soit probant. De ce fait nous invitons nos dirigeant à investir plus, afin de pouvoir pallier au problème de l'insécurité alimentaire. Intensifier les cultures iriguées, les culture de contre saison, valoriser les point d'eau pour se faire. 21. Karim Hussein, IFAD, Italy Dear Alexandra and Diane, Thank you very much for the opportunity to contribute to this debate. Armed conflict and the effects of state fragility may spill over borders, taking on a regional or global dimension. International support is often required to meet people’s basic needs, including security, and to ensure access to basic services according to humanitarian principles (e.g. neutrality; impartiality; do no harm; accountability; participation of affected populations). This is a very important theme for IFAD, particularly now as the organisation prepares strategic priorities for coming years, reviews achievements over recent years and begins consultations on the 10th replenishment of IFAD's resources for the period 2016-18. Engagement in fragile and conflictaffected states and situations is an important dimension to this process. IFAD's mandate to enable www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 17 poor people to overcome poverty covers all countries and regions that are internationally recognised as fragile states and situations and continues to finance projects and programmes in many contexts experiencing protracted crises linked to natural disasters, violent conflict, insecurity and instability. Therefore, IFAD has been reviewing its performance in fragile states and situations, reviewing priorities, strategies, instruments and best practices, as engagement in such situations will continue to be a priority in the coming years. Some elements of IFAD experience that might be useful in the context of this e-forum are outlined below. First, of the 95 countries in which IFAD had ongoing operations in 2012, a total of 38, or 40%, were classified as fragile. Out of the 254 ongoing projects, a total of 105, or 41%, were being implemented in fragile states. Similarly, 40% of the projects in the current portfolio are in fragile states. 46 fragile and conflict-affected countries will have IFAD allocations in the period 2013-15 and they will receive some 45% of the total allocations in the current cycle (2013-15). These included IFAD-financed programmes that continue to be implemented in often remote, rural areas across the world, for example in: Burundi, Haiti, Nepal, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Libya, Sierra Leone, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, South Sudan…. Indeed, IFAD is often one of the few international agencies to maintain operations and continue support to rural poverty reduction, capacity building and agricultural and rural development through long term crises and continues to support the strengthening of capacities for programme implementation, supervision and monitoring throughout crises. Third, IFAD-financed programmes prioritise the most vulnerable groups, particularly women, young people and the food insecure. IFAD’s approach in protracted crises is guided by its ‘Framework for bridging post-crisis recovery and long term development’ (1998), a ‘Crisis Prevention and Recovery Policy’ (2006), a consultation document for the EB on ‘IFAD’s role in fragile states’ (2008), evaluation insights on fragile states (2008). The Crisis Prevention and Recovery Policy reaffirms the need for IFAD to help poor rural people to increase their resilience to external shocks and their capacity to cope more effectively with crisis situations, and to restore the means of livelihood upset by crisis and recognises the need to tailor actions to the needs of individual countries. The policy identified three key strategic initiatives as the basis for the positive outcomes of IFAD interventions in crisis areas: (a) empowering communities, by building robust and transparent rural community-based organizations with clear objectives and access to resources to implement their own micro-projects, to ensure a role for rural poor people in the decision-making processes that affect their livelihoods; (b) supporting an active role for women in community organizations and in other local public governance institutions; and (c) mobilizing NGOs and civil society organizations to complement public administrations in providing services to rural communities. In October 2008, IFAD prepared a paper for its members reviewing 'IFAD's role in fragile states'. The review of project completion and project evaluation reports identified a number of key lessons to achieve better impact more consistently in fragile and conflict-affected states and situations. These included the need for: - More profound in-country knowledge, by investing more in analytical work and contextual studies in fragile states; - Clearer and simpler project objectives and design in fragile states; Better donor coordination; and - More direct IFAD involvement in project and programme supervision; The paper also noted that governance issues affecting IFAD’s programmes must be tackled at the national level, and that IFAD must carefully evaluate whether it is matching the right instruments to specific situations and whether these instruments are being used flexibly in fragile states. At the time www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 18 the paper was produced an undifferentiated approach was being used with respect to decisions regarding country programme managers (CPMs), country presence, supervision, quality enhancement procedures, etc. It is now recognised that the approach in fragile states and situations should allow for the provision of additional technical assistance for programme development if needed, and be sufficiently flexible to adapt projects and programmes over time. Recent reviews and evaluations of IFAD-financed programmes in fragile states indicate that they generally perform less well in relation to others in stable contexts, according to standard indicators. This experience is not restricted to IFAD – other IFIs are facing similar challenges. Traditional approaches and development financing models do not work as well in crisis contexts. Achieving results in fragile contexts and protracted crises requires more time and more resources than in stable settings, and at a greater risk. This seems to call for reflection on the appropriateness of the IFI financing models and approaches which sees state institutions as implementers of development assistance, in fragile states and situations and protracted crises. IFAD has committed to improve its operational effectiveness and performance in fragile states between 2013 and 2015, including special reporting on our work in fragile states in the annual 2013 Portfolio Review. In 2013-2015 IFAD will finance operations in a total of 98 countries. Of these, 48 are classified as fragile; 46 of them will receive IFAD financing. When analysing its development effectiveness in fragile states, IFAD has found that that it has been key to implement programmes at the community level with a high degree of participation, particularly of rural women. Also, that in line with its crisis prevention policy, IFAD will support conflict prevention by incorporating measures to mitigate the risk of foreseeable crises, natural and otherwise, and their impact on the Fund‘s intended beneficiaries during country strategy and project formulation. And that IFAD will continue to emphasize inclusive development and strengthening the capacities of the intended beneficiaries of IFAD-financed programmes as individuals, and to enhance the capacity of local organizations to cope with shocks when they occur. Concrete and effective ways for implementing any policy updates in practice must be set in place, ensuring, among other things, staff capacity, the allocation of adequate budgeting, and the setting up of realistic timeframes of engagement. Through a review of programmes in fragile and conflict-affected states and situations IFAD has identified a number of lessons to achieve the desired impacts in fragile states and protracted crises: (i) More profound in-country knowledge is needed; (ii) Project objectives and design in fragile states should be clearer and simpler. (iii) Donor coordination needs to be enhanced in fragile states, as the capacity for internal coordination among line ministries in the partner country also needs to be taken into account. (iv) IFAD needs to be more involved in supervision to help adapt and reshape projects and programmes during implementation. (v) Governance issues affecting IFAD’s programmes must be tackled at the national level. And (vi) IFAD must carefully evaluate whether it is matching the right instruments to specific situations and whether these instruments are being used flexibly in fragile states. The approach in fragile and protracted crisis contexts should allow for the provision of additional technical assistance for programme development if needed, and be sufficiently flexible to adapt projects and programmes over time. On accountability, I believe that it is clear that national and local governments, their international development partners and local people and their organizations are jointly accountable for progress on food security in protracted crisis contexts. But establishing effective ways to objectively identify and measure progress towards specific targets, but in an impartial and participatory way, remains a challenge. In reviewing practice in IFAD and among several other international development actors, we have also found that in order to improve programme performance and achieve development objectives in such difficult contexts it is necessary to: www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 19 * enhance capacity for situational and conflict analysis and ensure staff working in protracted crises benefit from tailored technical support; * clarify and update institutional strategies for working in such contexts, learning from the practical experiences of staff and external partners on what works best to maintain programme effectiveness in these situations while scrupulously observing humanitarian principles; * devote more resources to support operations in fragile and conflict-affected states and situations, and protracted crises; * update and harmonize guidelines on, approaches to, and instruments for the provision of assistance and implementation of operations in protracted crises; * adopt a flexible approach to programme design and implementation; and * enhance risk management in these contexts, including security of personnel. I personally think this could be supported by: (i) Collaboration among IFIs and other development agencies on approaches to operating in protracted crises, using existing networks such as the Busan New Deal Framework, the International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding, OECD’s INCAF and the UN’s Peacebuilding Support Office to exchange on successful approaches and experiences; 1. (ii) Enhancing sharing of field experience and development of in-House expertise in this area, informed by deeper linkages with expertise outside the organisation; and 2. (iii) Considering the utility and feasibility for establishing more tailored and flexible financing modalities in relation to fragile states and protracted crises, including perhaps a capacity to directly finance private sector and civil society organisations. Hoping this contribution to the debate is useful in the construction of the Agenda for Action, we look forward to reviewing the experiences and perspectives of other participants in this Community of Practice and sharing further as we seek to work in partnership to enhance our performance in protracted crises. For information, at the regional level IFAD has been supporting a number of initiatives to review experience in situations of fragility and protracted crises. I would like to mention, for example, the work by IFPRI that IFAD has supported on policies and investments for poverty reduction and food security in the Arab region: Beyond the Arab Awakening, http://www.ifpri.org/publication/beyondarab-awakening The Programme Management Department also completed a detailed review of IFAD's performance in Fragile States at the end of 2013. I can provide further information on these if useful. Best regards, Karim 22. European Commission, European Union In your experience, what are the key programmes and processes through which to mainstream food security into peacebuilding processes and get appropriate buy-in from all those involved? www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 20 The linkages between fragility and food insecurity are often complex and difficult to analyse. Vicious circles are usually existing between institutional weaknesses, political clashes, ethnic/religious/clan social conflicts, tensions around access to natural resources and natural disasters. Those circles are so convoluted that finding the first trigger element could become impossible or highly controversial. This is the case for the situation of high fragility, due to state failure of extreme institutional weaknesses (e.g. CAR). In other cases, the initial trigger element of a fragile situation could be more self-evidently linked to recurrent natural disasters driven by the growing pressure on natural resources (e.g. Sahel). In the two situations food security mainstreaming should be addressed differently. In the latter case, focus on natural resources sustainable management and direct food and nutrition security interventions aiming at reducing the initial source of tension should be put forward. In those cases the approach should be to put together actors from different experiences and perspectives to set up together a resilience building program (see the European Commission, ECHO, DEVCO and EEAS intervention on the e-conference “Addressing food insecurity in protracted crises: Resilience-building programming”) On the other hands, whenever the initial root cause is not easily or clearly identifiable, a pragmatic approach should be adopted. Given that i) the level of conflicts’ openness is usually going up and down depending on single contextual prompting elements, ii) initial and root causes of fragility are controversial, for analyse purpose only, the approach should be to cut down the situation at T˳. This would contribute to have a baseline through which understanding the present conflict status, recent trigger mechanisms, knowing the parties involved and the main issues. From this analysis, different scenarios are possible. The first, and most probable, is that the state is failed or so weak that no institution can ensure very basic services to the population. In this case the entry point should be state building together with the political dialogue with the conflicting parties. In those cases food security mainstreaming, who require minimal condition to be implemented, should be used for leveraging the state building and political dialogue itself, not as a goal per se. The second case would be the presence of functional states and institutions eventually involved in open conflicts. This scenario could be only addressed through policy dialogue supported by emergency operations to alleviate the immediate causes of the conflict. In those cases it is difficult to imagine genuine long term food and nutrition security interventions. 23. Manuel Castrillo, Proyecto Camino Verde, Costa Rica [English translation] Greetings to everyone. The current global context shows signs of increased openness in civic participation in industrial or agricultural societies. This is an opportunity for building bridges of rapprochement and dialogue between conflicting sectors. Heterogeneous structures are found in diverse scenarios. Although these can be feasible for listening to many partners they may also cause confusion by not focusing on the appropriate mechanisms for conflict resolution. I raise this consideration because, in case of brief or prolonged conflicts, the focus on food often remains in the background. I consider essential becoming aware of the fact that the impact of vulnerable groups or sectors at food level is part of the problem or the solution. Being present, although always essential, it frequently is. Peace is a right and food as well. Political conditions under which power is exercised without allowing individuals to manifest themselves are major constraints to achieving these rights. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 21 Hence, I deem relevant opening expression spaces where different groups in conflict can share their differences with respect and tolerance. The right to healthy food is enshrined in many constitutions and universal statements. It is understood that it is a fundamental basis for a decent quality of life. Opportunities granted to people to exercise this right will lead to fairer and more equitable states avoiding social problems amongst others. The allocation of land to socially risky groups and their training can certainly prevent conflict situations and strengthen the country. Monitoring mechanisms of international or national organizations must be efficient in their duties. To avoid mismanaging the aid received, various stakeholders in the conflict areas can act as supervisors. Remarkable persons to NGO’s and religious groups can and should participate to guarantee the access to vulnerable groups. In the short term, the peace process in Central America in the 80’s enhanced the conditions to improve the food of peasants and indigenous and provided economic stability for the future, enabling encouraging development. Conventions like Geneva’s should be stipulated where protection of people at risk and food resources required for avoiding related crises are considered. Of course, there is usually no political willingness and hunger is rather used as a deterrent and means of manipulation. Safeguards should be accomplished by strict economic sanctions for non compliance. Las organizaciones como la ONU, deben ser más rigurosas, no ser tan complacientes con intereses de países, que juegan con la vida humana. Es una realidad cruda, siempre el diálogo, será la herramienta para traer comprensión y tolerancia. Organizations such as the UN should be more rigorous and not so condescending with interests of countries playing with human life. It is a harsh reality. Dialogue will always be the tool to bring understanding and tolerance. Manuel Castrillo Costa Rica [Original contributon in Spanish] Saludos a todos. El actual contexto mundial nos muestra una mayor apertura en la participación de la ciudadanía, sea en sociedades industriales o agrícolas, siendo esto, una puerta para el establecimiento de puentes, de acercamiento y diálogo entre sectores en conflicto. En diversos escenarios encontramos estructuras hetereogéneas que pueden ser viables para escuchar muchos interlocutores, más también, pueden generar confusión al no enfocarse en el o los mecanismos propicios para la resolución del conflicto. Esto, lo planteo pues en el caso de conflictos prolongados o no, el foco sobre la alimentación muchas veces queda de lado, el asunto es tomar conciencia de que la afectación de grupos o sectores vulnerables en el aspecto alimenticio, es parte del problema o solución, está ahí, aunque no sea lo medular, y muchas veces lo es. La Paz es un derecho, la alimentación también. Las condiciones políticas en donde el poder se ejerce sin opción para que los individuos puedan manifestarse, son obstáculos importantes para la consecución de estos derechos, por esto la relevancia de la apertura de espacios de expresión, donde los diferentes grupos en conflicto puedan intercambiar con respeto y tolerancia sus diferencias. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 22 El derecho a una sana alimentación, está consagrado, en muchas constituciones y declaraciones universales; se entiende pues, que es base fundamental, para una calidad de vida digna. Las oportunidades que se brinden para que los pueblos ejerzan este derecho, darán sustento a estados más justos, más equitativos, evitando problemas sociales y otros. La asignación de territorios a grupos de riesgo social y su capacitación, bien puede evitar situaciones de conflicto y fortalecer el país. Los mecanismos de seguimiento de las organizaciones internacionales o nacionales, deben ser eficientes en su función. Diversos actores de las zonas conflictivas, pueden ser supervisores para evitar un mal manejo de las ayudas que llegan. Desde notables, ONG`S y grupos religiosos, pueden y deben intervenir para ser garantes del acceso a los grupos vulnerables. El proceso de Paz en Centroamérica en los 80`s, da como resultado, en el corto plazo, la mejora de condiciones para una mejor alimentación a campesinos e indígenas y estabilidad económica a futuro, y vislumbrando un desarrollo con esperanza. Deberían estipularse convenios como el de Ginebra, donde se contemple la protección de las personas en riesgo y los recursos alimentarios necesarios para evitar las crisis de alimentos, pero por supuesto, generalmente, no hay voluntad política y más bien se utiliza como medio de disuasión y manipulación el hambre de las personas. Las salvaguardas tienen que llevar sanciones económicas fuertes para quien las incumpla. Las organizaciones como la ONU, deben ser más rigurosas, no ser tan complacientes con intereses de países, que juegan con la vida humana. Es una realidad cruda, siempre el diálogo, será la herramienta para traer comprensión y tolerancia. Manuel Castrillo Costa Rica 24. Adam Kabir Dickinson, IAFN-RIFA, Costa Rica Thank you for the opportunity to participate in this discussion. As an organization involved in community-based solutions to food security and environmental protection, IAFN sees the importance of long-term, locally adapted plans for food security as a key to mitigating the impact, and contributing to the prevention of conflict situations brought about by resource scarcity. Environmental factors often play a role in the duration and severity of conflicts, and as such reducing environmental vulnerability plays an important role in crisis management. Thus, food security programs that address food production as well as environmental protecftion can have desirable benefits in terms of easing resource struggles through the provision of environmental services. IAFN's work puts an emphasis on communities facing food security challenges by implementing agroforestry systems that will improve food production while also reducing environmental vulnerability, for example through the protection of watersheds. By emphasizing environmental resilience and community governance alongside food security, communities find themselves betterequipped to deal with conflict situations. To learn more about IAFN and our work, please see www.analogforestry.org. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 23 25. Alexandra Trzeciak-and Duval and Diane Hendrick, conveners of the discussion Dear FSN Forum Participants, We have come to the end of our online discussion on Mainstreaming Food Security into Peacebuilding Processes. We wish to thank all who took the time to participate for your thoughtful and stimulating inputs, which will nourish the Agenda for Action for Addressing Food Security in Protracted Crises (CFS-A4A) to be submitted to the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) at its October meeting. In our message of 19 December 2013, we summarised the key messages and principles emerging from the discussion at that point. Since then, we have had rich, experience-based contributions from HenkJan Brinkman of the UN Peace Building Commission, George Kent of the University of Hawai’i (USA), Florence Egal from Italy, Petr Skripchuk of the National University for Water Resource Management (Ukraine), Stephanie Gill of Tearfund (UK), Noura Fatchima Djibrilla of ACFM Niger, Karim Hussein of IFAD, the European Union, Manuel Castrillo from Proyecto Camino Verde in Costa Rica and Adam Kabir Dickinson from IAFN, also Costa Rica . We thank you all. Your contributions have validated earlier messages, especially stressing the need for context specific, differentiated approaches based on profound in-country knowledge and analysis and inclusive participation (EU, Karim Hussein, Manuel Castrillo). You have also added essential messages, including: Integrating a peacebuilding approach into food security interventions is as (or more) critical as the reverse (Henk-Jan Brinkman); The international community should give greater emphasis to the human right to food and recognise the obligation to protect people through humanitarian assistance (George Kent, Manuel Castrillo); Leaders of the least developed countries should prioritise sufficient investment in agriculture, with due emphasis on irrigated crops, counter-seasonal production and water systems (Noura Djibrilla); Providers of assistance should recognise the need for greater financing flexibility and tailoring, as well as for more resources to support operations in countries in protracted crisis situations (Karim Hussein); The international community should enhance risk management and resilience building approaches, as well as develop standards and measures of progress (EU, Karim Hussein, Petr Skripchuk). As environmental factors often play a role in the duration and severity of conflicts, food security programs that address food production as well as environmental protection can have desirable benefits in terms of easing resource struggles (Adam Kabir Dickinson) And you have reminded the drafters of the CFS-A4A of numerous sources of previous work to draw upon. www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org Proceedings / 24 The quality of your contributions makes up for a relatively low number of participants in this ediscussion. For this reason, we are particularly grateful to Stephanie Gill, who has offered to gather inputs on the ground in Chad, Niger and Mali in the coming weeks. The consultative process and building engagement on the CFS-A4A continues. The initial Zero Draft draws on the outputs of the e-discussions to date (including this one), the inputs of a Technical Support Team, and benefits from the feedback of CFS Members and Participants over recent months and guidance of a high-level Steering Committee. The Zero Draft will be considered by CFS Members and Participants in a dedicated session on 56 March. At the end of April a Global Consultation will be held in Addis Ababa, with the aim of obtaining feedback and input from a broad range of stakeholders, in order to improve the existing draft and foster ownership of the principles at a global level. We hope you continue to provide your ideas and support for a strong CFS-A4A. We will keep you updated on opportunities and channels to do so. Vulnerable and food insecure people living in protracted crisis situations deserve fewer words and more action. Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval and Diane Hendrick, conveners of the discussion www.fao.org/fsnforum/protracted-crises fsn-moderator@fao.org