Running Head: SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

Sexual Orientation and Communication Satisfaction with Parents

Joshua Swan

Lewis-Clark State College

Jdswan@lcmail.lcsc.edu

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

1

Introduction

In the last 47 years, the United States of America has been evolving on its stance with the

LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) community. Starting with a revolution of angry

drag queens and queers at the Stonewall Riots on June 28th, 1969 (Lisker, 1969), the attitude

towards the LGBT community has slowly begun to change. Fast-forward to 2016, and the social

climate for LGBT people is drastically different with the ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges by the

U.S. Supreme Court (2015), and the passing of marriage equality for same-sex couples. The

ongoing battle faced by advocates and opponents seems to be that of nature vs. nurture. Are

people “born” gay? Is it decided through the birth order and the sex of older siblings (Bogaert,

2005)? Or, are people made gay through their environment and other influences? Is an

overbearing mother or absent father the reason a boy “goes gay?” This debate has been ongoing

for years, and, to this date, there have been no conclusive findings, but there are many myths and

hypotheses. One of the more interesting ideas of the nurture argument is the idea that gay/bi men

are just “momma’s boys,” and lesbians/bi women just grew up as complete tomboys. While these

generalizations may have been more sweeping and easier to make in the past, the acceptance of

the LGBT community in recent years has helped contribute to a social climate where gender

roles are less rigid than they used to be. Hopefully, this will lead to more ‘honest’ research about

communication between children and their parent of the opposite gender. This study seeks to

examine that correlation within the current the social climate. While the influence and inclusion

of the transgender participants is important as they are also a strong part of the LGBT

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

community, this research will be specific to the LGB population, as gender identity is another

dynamic which would add a greater level of complexity than the present study could support.

The results of this research will be valuable to social advocates, and possibly add more

weight to the argument of nature vs. nurture. An eventual discovery of the cause of

homosexuality will likely demystify the issue, and make it easier for parents of LGBT youth to

accept and understand their children. While this study will not be able to ultimately answer the

question, it will add weight to the scales.

2

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

3

Literature Review

Increase in LGB Research

Understanding how relatively recent the change in social climate and culture is, there

have been an increased number of articles concerning the LGB community. A particular area of

focus are journal articles within the field of Couple and Family Therapy (CFT) which explore a

variety of topics. Morin (1977) did a meta-analysis in the years between the years 1967 to 1974

that analyzed the content of the major CFT journals searching for articles pertaining to

homosexuality (Morin, 1977). These studies were followed up by an analysis done from the

years 1975 to 1995 (Clark & Serovich, 1997). A significant change was made regarding the

topics that were written about within these timeframes. While the original studies were able to

categorize the topics into 5 categories: assessment, causes, adjustment to, attitudes towards, and

special topics, the most recent study done updated this research from 1996 to 2010 and found

there were significant changes in the both the number and types of articles. The articles in this

arena had moved from etiological and treatment-based questioning, to more practical and varied

studies that discussed families or other mental health issues that may be related to or caused by

familial acceptance (or lack thereof) of someone being LGB (Hartwell, Serovich, Grafsky, &

Kerr, 2012).

Hypothesized Causes of Homosexuality

Addressing the reasons for variations in orientation other than heterosexuality has led

researchers to pose various hypotheses. Jenkins (2010) discusses some of the studies that have

been done.. Although these studies are promising in their initial findings, there has not been a

clear determinant of the cause. Jenkins believes the cause is some combination of both biological

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

4

and environmental factors, and states that there is more need to research the role that

familial/sociocultural environments have in this connection. Jenkins states that the majority of

the research has been heavily concentrated on male homosexuality and focused less on

bisexuality or female sexuality, in general. These are areas of research that need further

exploration (Jenkins, 2010).

Hypotheses have started leaning increasingly towards the biological argument in recent

years. The popular media has been shown to have an effect on this change. While part of the

process has been a slow coming out of those who are in the closet, being LGBT has become

more acceptable over the past decade. Pop music has helped influence attitudes regarding the

LGBT community, one song in particular that was researched was “Born This Way” by Lady

Gaga (Jang & Lee, 2014). An increase in songs about non-heteronormative orientations in pop

music has helped promote acceptance of the LGBT community. Another example of a popular

song that might be influencing this change in attitudes is Macklemore’s “Same Love.” These

songs lead the public to believe that there is no choice in being LGBT, and it is biological in

nature. The biological argument has been shown in a smaller research study to have an impact on

the acceptance of people who are LGBT, as they are believed to have no choice (Kasser, 1999).

Another hypothesis presented on the biological side of the argument is the birth order

hypothesis. This hypothesis is based on the idea that a woman’s body will start to reject the

testosterone of male children over the course of time, and with each subsequent male child, she

will have a built-up immunity to male fetuses. This will then lead to a higher likelihood that a

male child will be GBT. This hypothesis does not, however, account for a biological basis in

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

5

women (Jenkins, 2010). A study done by Bogaert in 2005, however, utilized a larger sample of

237 homosexual men, and did not support this hypothesis (Bogaert, 2005.)

Children and Communication Satisfaction

In regard to communication satisfaction, there was a study done that looked at ease of

communication between boys and girls and their fathers and mothers (Levin & Currie, 2010) the

children were not identified as being LGBT or otherwise. This study showed significant

differences between the ease and ability of communication children had with each parent. For

both genders, communication was reported as easy with their mother for 79% of the children.

Communication with their fathers, however, was reported as easy for about 62% of the boys and

only 44% of the girls. Ease of communication with the mother was by far a normal occurrence

for most of the participants in this study. Those who had the highest life satisfaction, though,

were those who reported having easy communication with their father. Considering that, both

boys and girls from single father families reported lower life satisfaction than those in a

household with both of their parents (Levin & Currie, 2010). In other words, ease of

communication with mothers was a far more consistent staple in the lives of children. When

paired with easy communication with fathers, children had a much higher life satisfaction.

Gender Nonconformity and Relationships

A study that analyzed sexual orientation and gender nonconformity (Rieger, Linsenmeier,

Gygax, & Bailey, 2008) found that children who identify as homosexual both recall and were

observed through the use of home videos to have exhibited more gender-nonconforming

behaviors than their heterosexual counterparts. This partially helps confirm that self-reports of

being gender-nonconforming are consistent with observable data, a limitation of recalling past

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

6

data was a concern for many studies. It also found that there was increased rejection from both

parents and especially peers. Another study (Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, & Perlman,

2004) verified that gender-nonconforming behavior was associated with parental and peer

rejection specifically for gay and bisexual men. It found that paternal rejection would lead into

adult attachment anxiety while maternal rejection did not. In the discussion, it also suggests that

the same gender parents may influence expectations and dynamics within same-sex relationships.

Consequently, a poor paternal relationship for a gay/bisexual man, or a poor maternal

relationship for a lesbian/bisexual woman may impact the attachment security in their romantic

relationships (Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, & Perlman, 2004). Paired with the previous

study mentioned by Levin & Currie, this data might suggest that, because of increased rejection

by parents for being gender-nonconforming as a “prehomosexual,” or someone whose sexual

orientation had yet to be established but later became homosexual, people who identify as LGBT

are likely to experience a more difficult communication with their parents, and therefore, a

decrease in life satisfaction.

Beard & Blakeman did a study in 2000 rooted in psychoanalytic theory that attempted to

correlate being a gay or bisexual man with higher rates of narcissism. While they were unable to

support this hypothesis, they did find some weak correlations with their hypothesis that instead

linked childhood gender-nonconformity to narcissistic symptoms due to parental rejection or a

lack of support. Higher self-esteem and more authenticity in life for gay or bisexual men were

predicted when there was a stronger relationship and more accepting communications with their

fathers (Beard & Bakeman, 2000).

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

7

A general study was done (not LGBT specific) overall on relationships between fathers

and mothers independently (Amato, 1994). While the gender of the child did not matter, it was

found that fathers contributed to better well-being of children in the measures of happiness, life

satisfaction, and psychological distress. These associations were found to make a difference

independent of the relationship and closeness with their mother. Although this study is perhaps

more general in regards to communication satisfaction, it offers an in-depth control measure for

the general community with a national random sample of 471 fully completed set of 5 interviews

taken over a 12-year time frame (Amato, 1994). Levin, Dallago, & Currie found that ease of

communication between children and parents actually is a higher indicator for high life

satisfaction than the structure of the family (Levin, Dallago, & Currie, 2011).

In 1973, a study looked further into the relationships of homosexual men and women (It

did not account for either bisexual or transgender persons), as well as their heterosexual

counterparts and examined their relationships with each of their parents (Thompson, Schwartz,

McCandless, & Edwards, 1973). While gender-nonconformity has been shown to present itself

in “prehomosexual” boys, there are, however, several points that are outdated with this particular

study. This was performed at a time when being LGBT was considered a psychological

dysfunction until it was removed completely from the American Psycological Associations DSM

III’s revision in 1986 (Herek, 1997). The majority of what America had considered “gay” was

very stereotypical. In the current socio-cultural climate, there is more diversity that is visible

within the LGBT community and society overall. This study draws many of its findings from

attempting to research gender identity, which is a different variable altogether. The researchers

ask questions that have the participants describe if they were athletic, coordinated, or clumsy, or

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

8

if the participants played baseball as kids. It is now understood that gender identity and sexual

orientation are two different concepts that need to be analyzed separately. The study claimed to

have found the cause for people being LGBT as being the presence of a weak or hostile father

and presence of a stronger mother in homosexual sons, but it more accurately verified some

stereotypes and found possible correlations (Thompson, Schwartz, McCandless, & Edwards,

1973).

In 1986, a study was done by Milic and Crowne that explored a psychoanalytic-based

hypothesis about the variations in non-heterosexual orientations. This study involved 40

Canadian males and worked to find a less hidden sample of homosexual men (Milic & Crowne,

1986 p. 240). This study confirmed that many homosexual men felt like their father was less

loving, and they had a more difficult relationship with their fathers than the relationships that the

heterosexual men had with their fathers. This study also found that the homosexual sample was

generally more “approval-dependent and defensive”(p. 240) than the heterosexual group, which

might have heightened the negative responses that the homosexual group had reported about the

negative reactions from their fathers (Milic & Crowne, 1986). Ten years later, Phelan (Phelan,

1996) recreated the study with a slightly larger sample totaling sixty people. While this study

supported Milic & Crowne’s findings, the sample was still relatively small. It was mentioned that

both studies ignored bisexuality and were unable to account for it. Another limitation that was

brought up was that socioeconomic variables might have had an effect, as well (Phelan, 1996).

A study by Savin-Williams suggests that, at least for gay males, the acceptance or

rejection from both parents only affects the self-esteem of the child if the child deems their

parent is an important figure in their life. For young girls, while their acceptance or rejection by

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS

9

their father only affected their self-esteem if they deemed their father important, their mother’s

acceptance or rejection affected their self-esteem regardless of the level of importance the girl

credits their mother in their life. This hints that there are differences in how gay/bisexual men

and lesbian/bisexual women deal with acceptance and rejection from their parents. The results of

the current study could potentially result in similar findings.

By narrowing down the variables for non heterosexual orientations, LGBT advocates will

be able to better help and serve the people who are newly out and their families. In a study by

Armesto & Weisman (2001), college students, even if they were not parents, were hypothetically

asked how they would feel if they had a gay or lesbian child. A large determining factor in how

they handled that situation was based on what they perceived the cause to be for their child’s

homosexuality. Parents were generally more accepting if they attributed homosexuality to

biological factors. If they attributed homosexuality to an internal cause that could be changed or

adjusted, parents were less likely to be supportive of the child. This finding supports the

attribution theory of Weiner (1980). Also, if the parents indicated that they would feel shame in

regards to their child coming out, they would often be more negative about the entire situation.

Shame was usually felt when the parents felt they were at fault. If the parents felt guilty, they

were more likely to be supportive and try to help their child and work to accept the child, no

matter the sexual orientation.

This research project might add weight to the nature vs. nurture argument. While it is not

within the scope of this study, if there is a variable for being LGBT which is eventually

identified, it may make it easier for parents to understand and accept their LGBT children. Most

research currently aligns the parental reaction to that of the grief process of losing a loved one

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 10

(Savin-Williams, Dubé, & Dube, 1998.) Although this needs further study, when research is able

to determine why people are LGBT, it will likely lessen the stages of anger and bargaining if

parents don’t blame themselves for things not under their control for why their children are

LGBT.

Although a good amount of research has been done, there is a lack of current research

done on parent-child relations and children being LGBT. Studies that have been done previously

in regards to these two topics have confused sexual orientation with gender identity in order to

support their hypotheses. In our current social climate, gender identity is more transparent than it

used to be, and, for that reason, there is value in reviewing the topic again. Little research has

been done, as well, on self-identified bisexual persons. As bisexuality has become more accepted

as a legitimate orientation, there is value in researching it, as well. While the transgender

community is a vital part of the overall LGBT community, the scope of this project is going to

focus purely on the sexual orientation factor of participants. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H: There is a correlation between being LGB (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual), and communication

satisfaction with the parent of the opposite gender.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 11

Methodology

This study was conducted with participants from the LGB (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual)

community and a heterosexual control group from the United States. The LGB participants were

gathered through a snowball sample on the social media website Facebook in LGB-centered

groups. As the study was conducted using a sample across social media, there were opportunities

to collect a sample of heterosexual responses. In order to achieve sufficient responses, surveys

were also distributed to classes in a small northwestern community college. In total, 387

respondents participated. Of these participants, 65 (17%) identified as straight males, 19 (5%)

identified as bisexual males, 71 (18%) identified as gay males, 166 (43%) identified as straight

women, 44 (11%) identified as bisexual women, and 22 (6%) identified as lesbians.

The study consisted of a questionnaire with 38 Likert-scaled questions and 3 questions

regarding nominal data including gender identity, sexual orientation, and the country of

residence. In order to keep the responses limited to a geographical area, as there are cultural

differences in family structures, responses were only accepted from participants who are U.S.

citizens. The instrument chosen for the questionnaire is Hecht’s Interpersonal Communication

Satisfaction Inventory (Rubin, Sypher, & Palmgreen, 1994). This instrument includes 19

questions, and was modified slightly to reflect recalled child-parent relationships. The survey

was duplicated so participants were able to respond in regard to both their mother or mother

figure and father or father figure. This inventory holds a high reliability coefficient of .90 when

used for recalled conversations. It is noted that, even when the inventory is modified, sufficient

reliability is found. This survey was offered online and took approximately 10 minutes to

complete. Surveys at the college were distributed on paper.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 12

Analysis

To analyze this data, a one-way ANOVA was applied for each gender with each parent to

test for significant differences in communication satisfaction between each different gender and

orientation and community satisfaction with their parents. this included all men and

communication satisfaction with their mothers, all men and communication satisfaction with

their fathers, all women and communication satisfaction with their mothers, and all women and

communication satisfaction with their fathers.

A T-test was then applied for each sexual orientation to see if there was a significant

difference for each between communication satisfaction with their mothers and fathers.

Results

Differences in Relationships by Sexual Orientation

Within each gender, a one-way ANOVA was applied for all three sexual orientations. For

males there was a statistically significant (p=.032) difference among the straight, bisexual, and

gay men with means of 3.30, 3.52, 3.37, respectively, for communication satisfaction with their

mother. There was also a statistically significant (p<.001) difference among the straight,

bisexual, and gay men with means of 3.28, 2.89, and 2.65, respectively, for communication

satisfaction with their father.

For women there is a statistically significant (p=.012) difference among straight,

bisexual, and lesbian women with means of 3.16, 3.09, and 2.90, respectively, for

communication satisfaction with their mother. Finally, there was a statistically significant

(p<.001) difference among straight, bisexual, and lesbian women with means of 3.19, 3.24, and

2.69, respectively, for communication satisfaction with their father. (see Appendix Table 1)

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 13

Differences between Parents

A T-Test was then applied to each demographic to determine if there was a significant

difference in communication satisfaction with their father and mother. For straight males,

differences in communication satisfaction between the mother (m=3.30) and the father (m=3.28)

were not statistically significant at p=.631. For bisexual males, differences in communication

satisfaction between the mother (m=3.52) and the father (m=2.89) were statistically significant at

p<.001. For gay males, differences in communication satisfaction between the mother (m=3.37)

and the father (m=2.66) were statistically significant at p<.001. For straight females, differences

in communication satisfaction between the mother (m=3.16) and the father (m=3.18) were not

statistically significant at p=.23. For bisexual females, differences in communication satisfaction

between the mother (m=3.09) and the father (m=3.24) were statistically significant at p=.019. For

lesbian females, differences in communication satisfaction between the mother (m=2.90) and the

father (m=2.69) were statistically significant at p<.001. (see Appendix Table 2)

Of the 38 questions, the only responses marked above a 4.0 on a scale of 1-5 (1 being low

and 5 being high) was the question, “I felt that we could easily laugh together,” in regards to gay

and bisexual men’s communication with their mother. The only question that averaged below a

2.0 was, “I felt like I could talk about anything with him,” in regards to communication with

their father. For this question, both gay men and lesbian women scored below a 2.0, and

bisexual men scored just slightly higher at 2.11. This was also the only question on which all 6

demographic groups scored below a 3.0.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 14

Discussion

It is important to note that this study did not seek to find causation for being LGB, but

merely sought to confirm a possible correlation. The results of this study highlight the disparity

in family communication for the LGB community. For both straight males and straight females,

the differences between communication satisfaction with both their mother and father weren’t

significant. Both gay males and bisexual males had higher communication satisfaction with their

mother as opposed to their father. For bisexual females, they had higher communication

satisfaction with their father as opposed to their mother. In the case of lesbian females, they had

higher communication satisfaction with their mothers as opposed to their fathers; however, both

of the scores were on the lower end of the scale reflecting a difficulty in communication with

both parents.

Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted for gay and bisexual males and bisexual females.

There is a correlation between being a gay male and bisexual male or female and communication

satisfaction with the parent of the opposite gender. The inverse of the hypothesis is accepted for

lesbian females.

These results help demonstrate the need for stronger communication in the event of

someone coming out as LGB to their parents. While it might be difficult for some parents to

recognize this lack prior to their child coming out, paying special attention to these

communication relationships during and after a child’s coming out could be especially helpful.

This study also helps begin the process of including bisexuality in research regarding family

communication. Sexual orientation is beginning to be seen by the public as a lot more varied

than just homosexual or heterosexual, it is important that we recognize that there are differences.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 15

For bisexual males, there is significantly higher communication satisfaction with both the mother

and the father when compared to gay males. Bisexual females also had higher communication

satisfaction with both their mother and father as compared to lesbian women; this might be for a

similar reason as bisexual males. In seeing this difference in both genders for this study, it raises

the question of how might data look in past research studies if respondents had been divided

beyond just homosexual and heterosexual.

The results of this study also reflect the masculine orientation of the United States as a

whole (Anderson, 2007). In regards to their fathers, both bisexual and gay males, as well as

lesbian females all reported significantly lower communication satisfaction. As communication

skills are typically considered more feminine or androgynous, the lower responses for

communication satisfaction for fathers show the divide in skills in our country. Unlike

communication satisfaction with the mothers, there weren’t any particularly high reports for

communication satisfaction with the fathers. In particular, one question, “I felt like I could talk

about anything with him” scored below a m=3.0 for all 6 demographics, lesbian females and gay

males averaged below a 2.0 for this question. This suggests a greater inability for people to

discuss topics with their fathers as opposed to their mothers. Perhaps this comes from expressing

emotion around feelings of attraction to the gender outside the social norm. Another noticeable

trend is that women tend to have lower communication satisfaction with both parents. This may

be partially explained as we live in a more masculine-oriented culture that tends to cater to

straight males (Anderson, 2007) where communication is a more feminine trait that women

might use more then men. In other words, the same amount of communication might lead to

higher satisfaction for men, who generally want less communication, and lower communication

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 16

satisfaction for women who generally want more, leading to the difference in responses. Further

research could include more qualitative studies regarding the nature of these parent-child

relationships more in-depth, or parent relationships and romantic relationship correlations. More

studies could also be done exploring varying gender identities and communication satisfaction

with parents.

Limitations

For this study, there were a few limitations that presented themselves. It is difficult in

studies like this to gather a true random sampling, therefore the sample was garnered through a

snowball sample. A sufficient number was reached for the sample size to reveal generalizable

findings. Additionally, many who work with the LGBT community are aware that there are a lot

of identities for both sexual orientation and gender. This study was unable to account for

variations in gender identity for people who identified their gender in ways other than cisgender

male and cisgender female and some of the lesser-known sexual orientations. In order to

generalize the data the researcher had to limit the orientation selections to heterosexual, bisexual,

and homosexual. Finally, as stated previously, this study is also only able to account for

correlation and not causation.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 17

Appendix

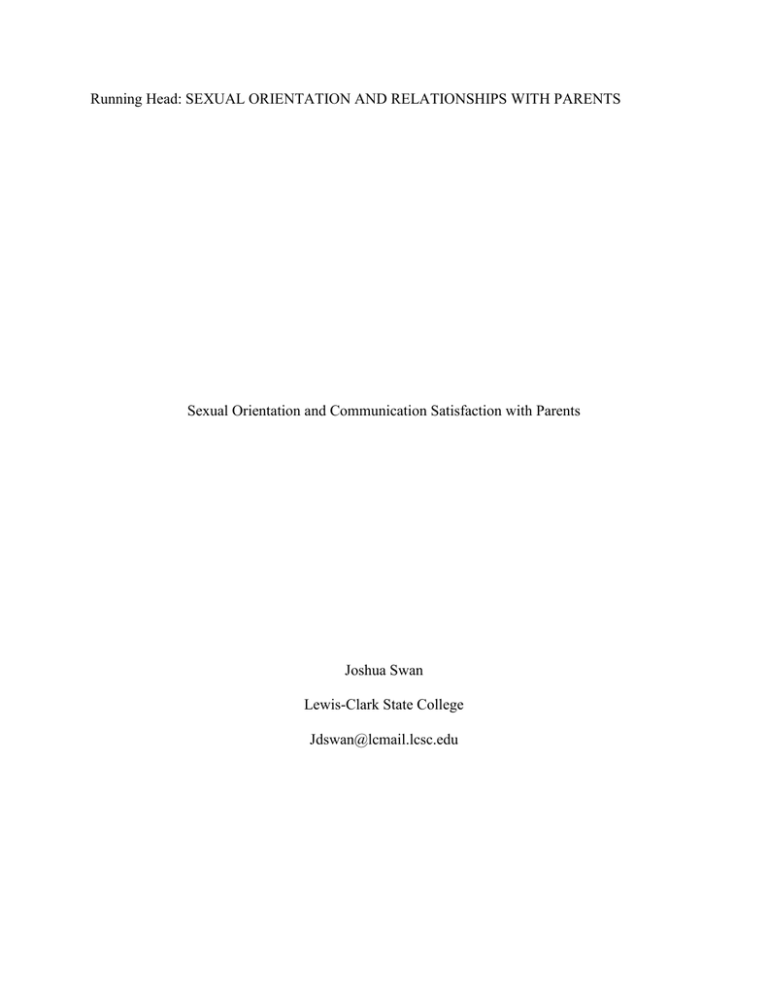

Table 1 Communication Satisfaction Means

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Male-Straight

Male-Bisexual

Male-Gay

Significance

Mother

m=3.30

m=3.52

m=3.37

p=.032

Father

m=3.28

m=2.89

m=2.65

p<.001*

Female-Straight

Female-Bisexual

Female-Lesbian

Mother

m=3.16

m=3.09

m=2.90

p=012

Father

m=3.19

m=3.24

m=2.69

p<.001*

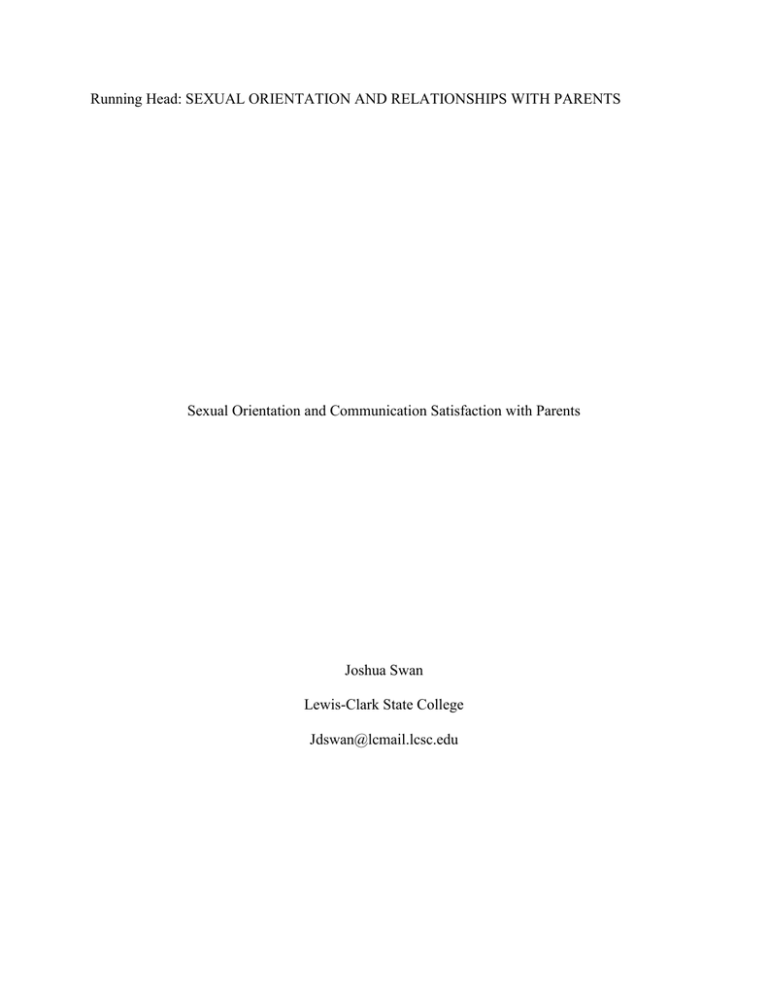

Table 2 Communication Satisfaction Means

T-Test- Differences between Parents

Mother

Father

Significance

Male-Straight

m=3.30

m=3.28

p=.631

Male-Bisexual

m=3.52

m=2.89

p<.001*

Male-Gay

m=3.37

m=2.65

p<.001*

Female-Straight

m=3.16

m=3.19

p=.23

Female-Bisexual

m=3.09

m=3.24

p=.019

Female-Lesbian

m=2.90

m=2.69

p<.001*

*Denotes statistical significance

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 18

References

Amato, P. R. (1994). Father-child relations, mother-child relations, and offspring

psychological well-being in early adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family,

56(4), 1031. doi:10.2307/353611

Andersen, P. A. (2007). Nonverbal communication: Forms and functions - 2nd edition (2nd

ed.). United States: Waveland Press.

Armesto, J. C., & Weisman, A. G. (2001). Attributions and Emotional Reactions to the

Identity Disclosure (‘Coming Out’) of a Homosexual Child*. Family Process, 40(2),

145–161. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100145.x

Beard, A. J., & Bakeman, R. (2000). Boyhood gender nonconformity: Reported parental

behavior and the development of narcissistic issues. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental

Health, 4(2), 81–97. doi:10.1080/19359705.2000.9962245

Bogaert, A. F. (2005). Gender Role/Identity and Sibling Sex Ratio in Homosexual Men.

Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 31(3), 217–227.

doi:10.1080/00926230590513438

Clark, W. M., & Serovich, J. M. (1997). Twenty Years and Still in the Dark? Content Analysis

of Articles Pertaining to Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Issues in Marriage and Family

Therapy Journals. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 23(3), 239–253.

doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1997.tb01034.x

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 19

Hartwell, E. E., Serovich, J. M., Grafsky, E. L., & Kerr, Z. Y. (2012). Coming Out of the Dark:

Content Analysis of Articles Pertaining to Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Issues in

Couple and Family Therapy Journals. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38,

227–243. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00274.x

Herek, G. (1997). Homosexuality and mental health. Retrieved April 12, 2016, from

http://lgbpsychology.org/html/facts_mental_health.html

Jang, S. M., & Lee, H. (2014). When Pop Music Meets a Political Issue: Examining How ‘Born

This Way’ Influences Attitudes Toward Gays and Gay Rights Policies. Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(1), 114–130.

doi:10.1080/08838151.2013.875023

Jenkins, W. (2010). Can anyone tell me why I’m gay? what research suggests regarding the

origins of sexual orientation. North American Journal of Psychology, 12(2), 279–295.

Kasser, J. D. O., Tim (1999). Attitude Change in Response to Information That Male

Homosexuality Has a Biological Basis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 25(2), 121–

124. doi:10.1080/009262399278913

Landolt, M. A., Bartholomew, K., Saffrey, C., Oram, D., & Perlman, D. (2004). Gender

Nonconformity, childhood rejection, and adult attachment: A study of gay men.

Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(2), 117–128.

doi:10.1023/b:aseb.0000014326.64934.50

Levin, K. A., & Currie, C. (2010). Family structure, mother‐child communication, father‐child

communication, and adolescent life satisfaction. Health Education, 110(3), 152–168.

doi:10.1108/09654281011038831

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 20

Levin, K. A., Dallago, L., & Currie, C. (2011). The association between adolescent life

satisfaction, family structure, family affluence and gender differences in Parent–

Child communication. Social Indicators Research, 106(2), 287–305.

doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9804-y

Lisker, J. (1969, July 6). Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad. . Retrieved from

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primaryresources/stonewall-queen-bees/

Milic, J. H., & Crowne, D. P. (1986). Recalled parent-Child relations and need for approval of

homosexual and heterosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15(3), 239–246.

doi:10.1007/bf01542415

Morin, S. F. (1977). Heterosexual bias in psychological research on lesbianism and male

homosexuality. American Psychologist, 32(8), 629–637. doi:10.1037/0003066x.32.8.629

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (Supreme Court of the United States 2015)

Phelan, J. (1996). Recollections of Their Fathers by Homosexual and Heterosexual Men.

Psychological Reports, 79(3), 1027–1034. doi:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.1027

Rieger, G., Linsenmeier, J. A. W., Gygax, L., & Bailey, J. M. (2008). Sexual orientation and

childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Developmental

Psychology, 44(1), 46–58. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46

Rubin, R. B., Sypher, H. E., & Palmgreen, P. (Eds.). (1994). Interpersonal Communication

Satisfaction Inventory. In Communication research measures: A Sourcebook (pp. 217–

222). New York: Guilford Publications.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH PARENTS 21

Savin-Williams, R. C. (1989). Parental influences on the self-esteem of gay and Lesbian

youths:. Journal of Homosexuality, 17(1-2), 93–110. doi:10.1300/j082v17n01_04

Savin-Williams, R. C., Dubé, E. M., & Dube, E. M. (1998). Parental Reactions to Their Child’s

Disclosure of a Gay/Lesbian Identity. Family Relations, 47(1), 7.

doi:10.2307/584845

Thompson, N. L., Schwartz, D. M., McCandless, B. R., & Edwards, D. A. (1973). Parent-child

relationships and sexual identity in male and female homosexuals and

heterosexuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41(1), 120–127.

doi:10.1037/h0035612

Weiner, B. (1980). A cognitive (attribution)-emotion-action model of motivated behavior:

An analysis of judgments of help-giving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

39(2), 186–200. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.186