The ‘Backstage’ Route to Modernity: Popular Culture as Hegemony in Modernus

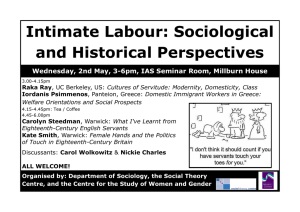

advertisement

The ‘Backstage’ Route to Modernity: Popular Culture as Hegemony in Eighteenth-Century England Modernus, modo (‘recent’, ‘now’), modernitas (‘modern times’) and moderns (‘men of today’) are terms used since the 10th century to define a new Weltanschauung opposed to the other (i.e. bourgeois) sense of Modernity which, Matei Călinescu contends, lost any metaphysical or rigorous ethics after the decline of religion. The great disenchantment generated by the awareness of the subjective time and self in eighteenth-century England highlighted, if not strengthened, the idea of relativism, of fluid boundaries between the bourgeoisie and the vulgar. Always seen from the perspective of the ‘Quality’, the other dark side of modernitas, or ‘us’, as Richard Hoggart argues, manifested itself as a counterpoised producer and consumer of cultural goods and public events. The unsacred time witnessed by the capitalist civilization was made up for by an underground tradition at war with the cultural and social prerequisites of the high class. The strong and rapid industrialisation, the urbanisation of England at the beginning of the eighteenth century developed the idea of luxury and hypocrisy among the elected and the division of labour and mundane pleasures among the vulgus. Thus capitalism gave birth, now more than ever, to a strong movement against the mainstream, which is the advent of the culture of the people. Tautologically speaking, the plebeians were the moderns of the present day who contributed to changing and challenging public authority and resisting to it by means of popular discursive practices. The backstage route to modernity, the very thesis I aim to consider in this paper, acquires a two-forked meaning, implying, on the one hand, the notion of ‘compulsion’, i.e. the strong, and, on the other, the popular strategies of the weak understood as adaptation (Fiske 35). The notion of ‘backstage’ will be related to what I call popular hegemony, namely the circulation of popular symbolic forms, in Pierre Bourdieu’s terms like diversion, entertainment and plebeian means of cultural production. Furthermore, I shall endeavour to conjoin this concept with the status of the bourgeoisie who began to acknowledge the pastimes and leisure of the low class in the latter half of the eighteenth century. The result is their mingling or, to put it differently, the circulation of social energy1 between the élite and ordinary people metonymycally labelled as Mr. and Mrs. Average or Stupidity. In my paper I shall briefly delve into the modus vivendi of the ‘disadvantaged’ and talk about a balance between the two social categories or, better say, about the exchange of habits, customs and traditions and their negotiations, despite the sheer criticism and violent attacks against the uncultivated. The texts I shall consider are all seen from a high-low position. Designed to be satires or pamphlets, genres typical of the Enlightenment literary conventions, they actually prove to be everyday notes or fragments about everyday people recorded by rich flâneurs driven by the pleasure of discovering the popular: the city of London with its debauched taverns and amphibious Houses of Entertainment, the delight taken in taking part in the Bartholomew fair, auxiliary or non-scientific means of religious faith best illustrated by astrology, heralded and praised by almanacs and blended with I borrow Stephen Greenblatt’s syntagm from Shakespearean Negotiations (Los Angeles: Berkeley, 1988) to underscore the idea of energeia whereby we come to grasp the collective physical and mental experiences, given the capacity of certain verbal and visual traces to produce and shape them. (italics mine) 1 the 1752 reform of the calendar that shook up the entire system of holidays and customs and, last but not least, the commodification of the Other as a simulated instance of British colonialism. Selective Bibliography: Backscheider, R. Paula, Spectacular Politics. Theatrical Power and Mass Culture in Early Modern England (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993). Bourdieu, Pierre, Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. by Richard Nice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984). Călinescu, Matei, Five Faces of Modernity (Duke University Press, 1987). Certeau, Michel de, The Practice of Everyday Life (1984) (Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 1988). Colley, Linda, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven: Connecticut, 1992). Fiske, John, Understanding Popular Culture (London: Routledge, 1989). Hoggart, Richard, The Uses of Literacy (London: Penguin Books, 1957). Jűrgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere - An Inquiry into the Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. by Thomas Burger (Massachusetts: Cambridge, the MIT Press, 1989). Langford, Paul, A Polite and Commercial People. England 1727-1783 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). Mullan, John and Cristopher Reid, Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture. A Selection, (Oxford University Press, 2000). BIO: Alexandru Dragoş IVANA is a junior lecturer in the English Department of the University of Bucharest. His main research interests include Enlightenment and Victorian literature, cultural and literary theory, comparative literature, history of ideas and city studies. He is now completing his PhD dissertation on Quixotism as political discourse in eighteenth-century English novel. Dragoş Ivana is treasurer of the Romanian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies and a founding member of the Centre of Excellence for the Study of Cultural Identity, University of Bucharest. In 2010 he has been honoured as ‘Bologna Professor’ by the Romanian National Association of the Student Organisations.