CHAPTER 5

advertisement

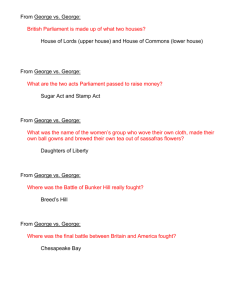

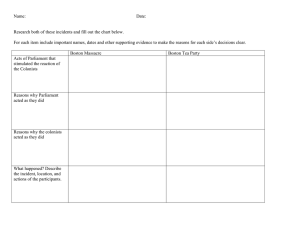

CHAPTER 5 The American Revolution: From Elite Protest to Popular Revolt, 1763–1783 SUMMARY This chapter covers the years that saw the colonies emerge as an independent nation. The colonial rebellion began as a protest on the part of the gentry, but military victory required that thousands of ordinary men and women dedicate themselves to the ideals of republicanism. I. STRUCTURE OF COLONIAL SOCIETY In the period following the Seven Years' War, Americans looked to the future with great optimism. They were a wealthy, growing, strong, young people. A. Breakdown of Political Trust There were suspicions on both sides of the Atlantic that the new king, George III, was attempting to enlarge his powers by restricting the liberties of his subjects, but the greatest problem between England and America came down to the question of parliamentary sovereignty. Nearly all English officials assumed that Parliament must have ultimate authority within the British Empire. B. No Taxation Without Representation: The American Perspective The Americans assumed that their own colonial legislatures were in some ways equal to Parliament. Since Americans were not represented at all in Parliament, only the colonial assemblies could tax Americans. C. Ideas About Power and Virtue Taxation without representation was not just an economic grievance for the colonists. They had learned by reading John Locke and the "Commonwealthmen" that all governments try to encroach upon the people's liberty. If the people remained "virtuous," or alert to their rights and determined to live free, they would resist "tyranny" at its first appearance. II. ERODING THE BONDS OF EMPIRE England left a large, expensive army in America at the end of the French and Indian War. To support it, England had to raise new revenues. A. Paying Off the National Debt In 1764 Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which was clearly designed to raise revenue and not just regulate trade. Merchants protested, but most American ignored it. B. Popular Protest The Stamp Act united the gentry and the mass of the population. The protest spilled into the streets, and groups of workingmen, organized as the Sons of Liberty, rioted and pressured tax collectors to resign. Boycotts became popular and allowed women to enter the protest. The more moderate protestors met at a Stamp Act Congress and petitioned the King and Parliament for repeal. C. Failed Attempt to Save the Empire The American protest coincided with a political crisis in England. A new government took office, sympathetic to English merchants whose business was hurt by turmoil in America. The new ministry wanted to repeal the Stamp Act, but dared not appear to be giving in to the Americans. Repeal was therefore tied to the Declaratory Act of 1766 which claimed that Parliament was sovereign over America "in all cases whatsoever." While the crisis of 1765 did not turn into rebellion, the Stamp Act controversy did cause the colonists to look upon English officials in America as alien representatives of a foreign government. D. Fueling the Crisis In 1767, Charles Townshend, chancellor of the exchequer, came up with a new set of taxes on American imports of paper, lead, glass and tea. Townshend also created the American Board of Customs Commissioners in order to ensure rigorous collection of the duties. Americans again resisted. The Sons of Liberty organized a boycott of English goods, and the Massachusetts House of Representatives sent a circular letter urging the other colonial assemblies to cooperate in protesting the Townshend Acts. When the English government ordered the Massachusetts assembly to rescind its letter, ninety-two of the representatives refused, and their defiance inspired Americans everywhere. E. Fatal Show of Force In the midst of the controversy over the Townshend taxes, the English government, in order to save money, closed many of its frontier posts in America and sent troops to Boston. Their presence heightened tensions. On March 5, 1770, English soldiers in Boston fired on a mob and killed five Americans. Just when affairs reached a crisis, the English government changed again. Lord North headed a new ministry and repealed all of the Townshend taxes except for the duty on tea, which North retained to demonstrate Parliament's supremacy. E. Last Days of the Old Order, 1770--1773 Lord North's government did nothing to antagonize the Americans for the next three years, and a semblance of tranquility characterized public affairs. Customs collectors in America, however, contributed to bad feelings by extorting bribes and by enforcing the trade acts to the letter, while radicals such as Samuel Adams still protested that the tax on tea violated American rights. Adams helped organize committees of correspondence that built up a political structure independent of the royally established governments. F. The Final Provocation: The Boston Tea Party In 1773, Parliament aroused the Americans by passage of the Tea Act. This act, designed to help the East India Company by making it cheaper for them to sell tea in America, was interpreted by Americans as a subtle ploy to get them to consume taxed tea. In Boston, in December 1773, a group of men dumped the tea into the harbor. The English government reacted to the "Tea Party" with outrage and passed the Coercive Acts, which closed the port of Boston and put the entire colony under what amounted to martial law. At the same time, Parliament passed the Quebec Act, establishing an authoritarian government for Canada. The English considered this act in isolation from American affairs, but the colonists across the continent saw it as final proof that Parliament was plotting to enslave America. They rallied to support the Boston colonists and protest the British blockade. The ultimate crisis had now been reached. If Parliament continued to insist on its supremacy, rebellion was unavoidable. Ben Franklin suggested that Parliament renounce its claim so that the colonies could remain loyal to the king and thus remain within the empire. Parliament rejected this advice. III. STEPS TOWARD INDEPENDENCE Americans organized their resistance to England by meeting in a continental congress. This section traces the major events, from the seating of the First Continental Congress in September 1774 to the decision for independence in July 1776. A. Shots Heard Around the World On April 19, 1775, a skirmish broke out between Americans and English troops in Lexington, Massachusetts. The fighting soon spread, and the English were forced to retreat to Boston with heavy losses. B. Beginning "The World Over Again" The Second Continental Congress took charge of the little army that had emerged around Boston by appointing George Washington commander. The English government decided to crush the colonists by blockading their ports and hiring mercenary troops from Germany. Royal governors urged slaves to take up arms against their masters. These actions infuriated the colonists. Thomas Paine, in his pamphlet Common Sense, pushed them closer to independence by urging Americans to cut their ties to England. On July 2, 1776, Congress voted for independence, and on July 4, Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, a statement of principles that still challenges the people of the world to insist upon their rights as humans. IV. FIGHTING FOR INDEPENDENCE In the ensuing war, the English had a better-trained army than did the Americans, but England's supply line was long, and the English army faced the task not only of occupying terrain, but also that of crushing the spirit of a whole people. A. Building a Professional Army Washington realized that America would eventually win independence if only he could assemble enough able troops and keep his army intact. B. Testing the American Will During July and August 1776, English forces routed the American army on Long Island, captured New York City, and forced Washington to retreat through New Jersey. C. "Times That Try Men's Souls" As Washington's army fled toward Philadelphia, the English military authorities collected thousands of oaths of allegiance from Americans, many of whom had supported independence. The cause seemed lost, but Washington rekindled the flame of resistance by capturing two English outposts in New Jersey, Trenton and Princeton. D. Victory in a Year of Defeat In 1777, General John Burgoyne led English forces out of Canada in a drive toward Albany, New York. Americans interrupted Burgoyne's supply lines and finally forced him to surrender at Saratoga, New York. General William Howe, who was supposed to help Burgoyne, instead decided to capture Philadelphia, which he did easily. Washington's discouraged army spent that miserable winter at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. E. The French Alliance France supplied the Americans with arms from the beginning of hostilities. After Saratoga, England feared an open alliance between France and America and proposed peace. Parliament offered to repeal all acts passed since 1763, to respect the right of Americans to tax themselves, and to withdraw all English troops. The Americans, however, preferred full independence and allied themselves with France in 1778. F. The Final Campaign After 1778, the English turned their attention to securing the South. They took Savannah and Charleston, and in August 1780, routed an American army at Camden, South Carolina. Washington sent General Nathanael Greene to the South to command American forces, and Greene's forces defeated English general Lord Cornwallis in several battles. When Cornwallis took his army to Yorktown, Virginia, for resupply, Washington arranged for the French navy to blockade Chesapeake Bay while the Continental Army marched rapidly to Yorktown, where Cornwallis was trapped. He surrendered his entire army on October 19, 1781. The English government now realized it could not subdue the Americans, and began to negotiate for peace. V. THE LOYALIST DILEMMA Americans who had remained openly loyal to the king during the Revolution received poor treatment from both sides. The English never fully trusted them, and the patriots took away their property and sometimes imprisoned or executed them. When the war ended, more than one hundred thousand Loyalists left the United States. VI. WINNING THE PEACE Ben Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay negotiated the peace treaty that ended the evolutionary War. By playing France against England, the Americans managed to secure highly favorable terms: independence and transfer of all territory east of the Mississippi River, between Canada and Florida, to the Republic. VII. CONCLUSION: PRESERVING INDEPENDENCE The American Revolution was more than armed rebellion against England; it was the beginning of the construction of a new form of government. The question had yet to be decided whether this would be a government of the elite or a government of the people.