You DO NOT need to write this section. It... for your review. CHAPTER 14 THE SECTIONAL CRISIS

advertisement

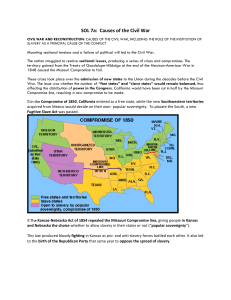

CHAPTER 14 THE SECTIONAL CRISIS TOWARD DISCUSSION - You DO NOT need to write this section. It is for your review. POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY American politicians are at their most creative when faced with a controversy they want to evade. It is then that they spin webs of mystification, using the threads of high-sounding rhetoric. In the 1850s, politicians meant to befuddle voters by concocting “popular sovereignty.” The expression fooled some of the people some of the time, and will probably confuse your students today. You will have to explain that most of the fifty states began life as territories, owned and governed by Congress. Since nobody wanted territories to remain territories forever, Congress worked out an intelligent method for bringing territories into statehood. In the first stage, Congress appointed a governor and opened a land office. The first people who moved in had access to good land, but they gave up, temporarily, the right to vote. There was no self-government at all during the first phase of a territory. As the population grew, the people acquired more self-government and eventually were allowed by Congress to write a constitution. If Congress approved the constitution, the territory became a state. Congress, in short, was involved in every stage of a territory’s evolution, but especially so during the first stage, when only the appointed governor yielded political authority. Congress gave its governors detailed instructions when they were appointed and in the territories of the Old Northwest (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan), Congress told the governors to prohibit slavery. All of those territories became free states. While the Northwest territories were moving toward non-slave statehood, slaveholding Southerners insisted that the Southwest territories (Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi) be opened to them. Congress did not have the stomach to write instructions giving explicit approval to slavery, so it simply omitted any mention of the subject from the governors’ instructions, knowing that the governors would welcome slaveholders, who were rich and powerful men. Every territory in which Congress allowed slaveholders to settle became slave states, a result that should have surprised no one. Nevertheless, most Northerners were shocked in 1817 when the Missouri Territory applied for statehood with a constitution that incorporated slavery. When Missouri had been first organized as a territory, Congress, as usual, had given the governor no instructions about slavery, and the governor, as usual, allowed slaveholders in. As usual, again, the slave-owners soon dominated the territory economically, socially, and politically. When they wrote a constitution and sent it to Congress, they expected the usual rubber-stamp approval. Instead, northern members of the House of Representatives rebelled against a policy that would give all the territories to the southern slave masters. The House voted to delay statehood for Missouri until she changed her constitution to abolish slavery. The resulting controversy was settled by the famous Missouri “Compromise.” Congress promised that it would prohibit slavery from any territory carved out of the Louisiana Purchase above the line 32°, 30’. The territorial issue seemed solved, but as the nation expanded, the issue kept cropping up, and each time it did, it aroused more bitter passions in the North and South, making it ever more difficult to compromise. By 1850, when Congress had to decide what to do with the New Mexico and Utah territories, recently taken from Mexico, the controversy was so severe that the nation was on the brink of civil war. It was then that the politicians came up with “popular sovereignty.” Congress suddenly discovered that it was undemocratic for Congress to tell the people of a territory thousands of miles away how they should run their lives. Let the people decide! In fact, the “people” in the first stage of a territory had no right whatsoever to govern themselves, and had absolutely no mechanism for keeping slave-owners out, unless they resorted to terrorism. No territorial governor would keep out slavery unless he was specifically ordered by Congress to do so, and once slaveowners entered a territory, that territory was doomed to become a slave state. It cannot be emphasized enough that “popular sovereignty” was a fraud meant to deceive Northerners. In the Utah Territory, for example, the governor was instructed to stamp out polygamy, and when the Mormons there refused to obey the law, Congress sent in the United States Army. So much for allowing the people of the territory to run their own lives! Popular sovereignty gave the Utah and New Mexico territories to the slaveholders, but the North might have shrugged off the loss because it would take ages for those territories to become states. Congress, however, made a colossal error in 1854 by applying popular sovereignty to territories that would be ready for statehood very quickly. The Kansas-Nebraska Act organized those territories by repealing the Missouri Compromise, which would have required Congress to instruct the governors to ban slavery. Congress would give no instructions to the governors and would let the people decide their own future, but most Northerners now understood that unless Congress banned slavery in the first stage of a territory’s existence, that territory would become a slave state. Outraged by yet another giveaway to the South, Northerners rose up in fury against the established political parties and cried out for new men and a new party to stop the expansion of slavery into the territories. Abe Lincoln and the Republican party stepped forth to fill that role. RELIVING THE PAST By the 1850s, North and South had become so antagonistic that one section’s hero almost automatically became the other’s villain. John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry scared the South; his execution sickened the North. Brown went to his death with grim determination, convinced as he wrote in his last note that “the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with Blood.... “ Richard A. Warch and Jonathan F. Fanton have edited the volume on John Brown in the Great Lives Observed Series (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973), which includes Brown’s last letters and statements, trial transcripts, and samples of northern and southern opinions on the raid. The sectional controversy was most apparent in Congress, where it was becoming increasingly difficult to compromise. A good instance of the deteriorating conditions was the remarkable difficulty in electing a Speaker of the House in the first session of the Thirty-Fifth Congress, which opened on December 3, 1849, and which would have to settle the status of the Mexican cession. Howell Cobb of Georgia and Robert C. Winthrop of Massachusetts battled through sixty-two ballots without either man achieving a majority of the House. Cobb finally won when the rules were changed to allow for a plurality. The ballots, with occasional shouts from the floor, are recorded in Abridgment of the Debates of Congress, sixteen volumes edited by Thomas Hart Benton, a noted politician of the era (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1861). The Abridgment also is an excellent source for the give and take of political discourse during the entire period it covers. Begin copying the review here: BROOKS ASSAULTS SUMNER IN CONGRESS The author uses the assault by a Southern senator on a Northern senator to illustrate the depth of bitter feelings between North and South. It was only through astute political maneuvering that a civil war was postponed for another decade. THE COMPROMISE OF 1850 In the 1840s, the North and South differed violently over whether slavery should be allowed to extend into the territories. Professional politicians, however, successfully mediated the conflict. A. The Problem of Slavery in the Mexican Cession Traditionally, slavery had been kept out of American politics, with the result that no practical program could be devised for its elimination in the southern states. Congress, however, had the power to set the conditions under which territories became states and to forbid slavery in new states. In the 1840s, as the result of expansion, Congress faced the problem of determining the status of slavery in the territories taken from Mexico. B. The Wilmot Proviso Launches the Free-Soil Movement As soon as the United States declared war against Mexico, antislavery groups wanted to make sure that slavery would not expand because of American victory. David Wilmot introduced a bill in Congress that would have banned all African Americans, slave or free, from whatever land the United States took from Mexico, thus preserving the area for white small farmers. This blend of racism and antislavery won great support in the North, and in a clearly sectional division, the House of Representatives passed the Proviso, while the Senate defeated it. The battle over the Proviso foreshadowed an even more urgent controversy once the peace treaty with Mexico was signed. C. Squatter Sovereignty and the Election of 1848 The issue of slavery in the Mexican cession became an issue in the 1848 election. Democratic presidential candidate Lewis Cass offered a clever solution. He proposed that Congress allow the settlers in the territories to decide the issue (popular sovereignty). The proposal found support among antislavery forces, who assumed that the territorial settlers would have a chance to prohibit slavery before it could get established. Popular sovereignty, however, was unacceptable to those who wanted a definite limit placed on the expansion of slavery. The Free-Soil party was formed, and it ran Martin Van Buren for president. The Whigs nominated war hero Zachary Taylor, who took no stand on the territorial question and who won with less than half the popular vote. D. Taylor Takes Charge Taylor proposed to settle the controversy by admitting California and New Mexico as states right away, even though New Mexico had too few people to be a state. The white South reacted angrily. Planters objected that they had not yet had time to settle the new territories, which would certainly ban slavery if they immediately became states. A convention of the southern states was called to meet at Nashville, perhaps to declare secession. E. Forging a Compromise The Whig leader, Henry Clay, put together a compromise package. The North would get California as a free state and a prohibition on the slave trade in the District of Columbia; the South got a strong fugitive slave law and a chance to settle the New Mexico territory, which was also enlarged. The Fugitive Slave Law turned out to be the most troublesome part of the compromise. Abolitionists, especially black abolitionists, became very active in helping slaves to escape from the South to refuge in Canada, and some slaveholders pushed their power to recapture slaves in the most provocative manner. One even insisted on deporting a slave from Boston even though the United States army had to be called on to subdue the crowd of rescuers. When Taylor, who opposed the compromise, died in August 1850, the Democrats, led by Stephen Douglas, adopted each of Clay’s proposals as a separate measure and changed them slightly. The Democrats, for example, extended popular sovereignty to the Utah Territory. No single bill was backed by a majority of both northern and southern congressmen, but a combination of northern Democrats and southern Whigs passed each separate measure. The South accepted the Compromise of 1850 as conclusive and backed away from threats of secession. In the North, the Democratic party gained popularity by taking credit for the compromise, and the Whigs found it necessary to cease their criticism of it. POLITICAL UPHEAVAL, 1852-1856 The sectional disputes aroused by the controversy over slavery in the new territories had been successfully handled by the Whigs and Democrats. In the 1850s, these parties collapsed as the sectional struggle raged without restraint. A. The Party System in Crisis Once the Compromise of 1850 seemed to have settled the territorial controversy, Whigs and Democrats looked for new issues. The Democrats claimed credit for the nation’s prosperity and promised to defend the compromise. Whigs, however, could find no popular issue and began to fight among themselves. Their candidate in 1852, Winfield Scott, lost in a landslide to Democrat Franklin Pierce, a colorless nonentity. B. The Kansas-Nebraska Act Raises a Storm In 1854, Stephen Douglas introduced a bill to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territories. These areas were north of the Missouri Compromise line and had been off limits to slavery since 1820, but Douglas proposed to apply popular sovereignty to them in an effort to get southern votes and avoid another controversy over territories. Douglas expected to revive the spirit of Manifest Destiny for the benefit of the Democratic party and for his own benefit, when he ran for president in 1860. The South insisted, and Douglas agreed to add an explicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, thus provoking a storm of protest in the North, where it was felt that the South had broken a long-established agreement. The Whig party, unable to decide what position to take on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, disintegrated. The Democratic party suffered mass defections in the North. In the congressional elections of 1854, coalitions of “anti-Nebraska” candidates swept the North, and the Democrats became virtually the only political party in the South. In the midst of this uproar, President Pierce made an effort to buy, or seize, Cuba from Spain, but northern anger at any further extension of slavery forced the president to drop the idea. C. An Appeal to Nativism: The Know-Nothing Episode As the Whigs collapsed, a new party, the Know-Nothings, or American party, gained in popularity. The Know-Nothing party especially appealed to evangelical Protestants, who objected to the millions of Catholics immigrating to America. By the 1850s, the Know-Nothings also picked up support from former Whigs and Democrats disgusted with politics as usual. In 1854, the American party suddenly took political control of Massachusetts and spread rapidly across the nation. In less than two years, the KnowNothings collapsed, for reasons that are still obscure. Most probably, Northerners worried less about immigration as it slowed down, and turned their attention to the slavery issue. D. Kansas and the Rise of the Republicans The Republican party emerged as a coalition of former Whigs, Know-Nothings, Free-Soilers, and Democrats by emphasizing the sectional struggle and by appealing strictly to northern voters. Republicans promised to save the West as a preserve for white, small farmers. Events in Kansas helped the Republicans. Abolitionists and proslavery forces raced into the territory to gain control of the territorial legislature. Proslavery forces won and passed laws that made it illegal even to criticize the institution of slavery. Very soon, however, those who favored free soil became the majority and set up a rival government. President Pierce recognized the proslavery legislature, while the Republicans attacked it as the tyrannical instrument of a minority. In Kansas, fighting broke out, and the Republicans used “Bleeding Kansas” to win more northern voters. E. Sectional Division in the Election of 1856 The Republicans, who sought votes only in the free states, nominated John C. Frémont for President. The Know-Nothings ran ex-President Millard Fillmore as a champion of sectional compromise. The Democratic candidate, James Buchanan, defended the Compromise of 1850 and carried the election, despite clear gains for the Republicans. THE HOUSE DIVIDED, 1857-1860 The long sectional quarrel convinced North and South that they were so different in culture that they could no longer coexist in the same nation. A. Cultural Sectionalism Cultural and intellectual cleavages surfaced in the 1840s. Even religion divided North and South. Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians split into northern and southern denominations because of their attitudes toward slaveholding. Southern literature romanticized life on the plantation, and the South attempted to become intellectually and economically independent in preparation for nationhood. At the same time, northern intellectuals condemned slavery in prose and poem. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, was an immense success in the North. B. The Dred Scott Case The Supreme Court had a chance to decide the issue of slavery in the territories when it agreed to consider the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857. Instead of limiting itself to a narrow determination of the case, the Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise had been unconstitutional because Congress could not restrict the right of a slaveowner to take his slaves into a territory. The ruling outraged the North and strengthened the Republicans. C. The Lecompton Controversy Once again, events in Kansas created sectional conflict. The proslavery faction met in a rigged convention at Lecompton to write a constitution and apply for admission as a state. Free-Soilers in Kansas overwhelmingly rejected the Lecompton constitution, but President Buchanan and the Southerners in Congress accepted it and tried to admit Kansas as a state. The House defeated this attempt. The Lecompton constitution was referred back to the people of Kansas, who repudiated it. The Lecompton controversy split the Democrats when Douglas broke with Buchanan over the issue, but Douglas made himself unpopular in the South by doing so. D. Debating the Morality of Slavery In 1858, Republican Abraham Lincoln faced Democrat Stephen Douglass in the Illinois Senate race. In debates, Lincoln claimed that there was a southern plot to extend slavery throughout the nation. He promised to take measures that would ensure the eventual extinction of the institution. Above all, Lincoln made the point that he considered slavery a moral problem, while Douglas did not. Douglas answered by accusing Lincoln of favoring racial equality, a potent charge that forced Lincoln to defend white supremacy. Lincoln lost the election, but gained a national reputation. E. The South’s Crisis of Fear A series of events in 1859 and 1860 convinced Southerners that Republicans intended to foment rebellion among African Americans and white small farmers. John Brown tried to capture an arsenal at Harpers Ferry in order to arm slaves. When Brown was executed for treason, the North mourned him as a martyr. The white South was disgusted and became convinced that the Republican party would use armed force to abolish slavery. The only solution, it seemed, was to secede if the next president was a Republican. F. The Election of 1860 Republicans nominated Lincoln in 1860 because he was from Illinois and because he was not as controversial as other Republican leaders. In order to widen the party’s appeal, the Republicans promised high tariffs for industry, free homesteads for small farmers, and government aid for internal improvements. Democrats could not agree on a candidate. The northern wing nominated Stephen Douglas; the southern Democrats nominated John Breckinridge. The Constitutional Union party ran John Bell, who promised to compromise the differences between North and South. Lincoln received less than 40 percent of the popular vote, but won virtually every northern electoral vote, giving him the victory. CONCLUSION: EXPLAINING THE CRISIS The breakup of the Union would not have happened without slavery or the rise of a strictly sectional party like the Republicans. But the conflict arose from a fundamental difference between two different ideals of society. The South saw itself as paternalistic, generous, and prosperous, and defended slavery on the grounds of race. The North, inspired by evangelical Protestantism, believed that each person should be responsible for himself and free to make his own way in the world. To the North, slavery was tyrannical and immoral.