ENGL&101 – English Composition I : then

advertisement

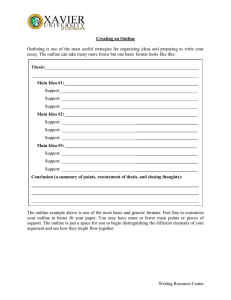

ENGL&101 – English Composition I Helpful Tips for Writing Essays The point: Form your own ideas and support them with an argument. You think about an issue, an idea, a text, or several texts in a complex (critical) way, and then come up with the argument you want to make. Essay-writing is a challenge; if it were easy, you wouldn’t need college. 1. THESIS STATEMENTS: The “backbone” of an essay is the thesis, which is your argument, your opinion, the point of your essay in a nutshell. It is a focused, complex, relevant, and arguable assertion. A good thesis makes an assertion that not everyone will agree with and which needs further support and explanation. A good assertion looks beyond what is obvious to say about a given subject and is more than one sentence. It may be rewritten several times as you draft. The thesis statement goes at the end of your introduction and can be more than one sentence. Thesis statements that don’t work because they are not arguments: 1. A list with no overall point: “This essay mentions race, identity, and language.” Remember, your task is to find a specific angle from which to argue. Though you will summarize in your essay, your thesis should not be limited to summary. 2. A statement of the obvious: “David Sedaris has a disability.” This is an observation, which is only the first step to analysis. 3. An unprovable opinion: “Nicholas Carr says the Internet makes us lazy but I disagree.” Your opinion, while valid, is not analysis; like observations, opinions are only part of the equation. Here’s an example of a good (but not perfect!) two-sentence thesis statement: 1) In his essay “Small Change: Why The Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted,” Malcolm Gladwell argues that social networks like Facebook make it easier for activists to advertise their causes but harder for real social change to occur. Though I agree with Gladwell that online activism is limited, my own experiences as a member of several online social action groups illustrate the important role such groups play in motivating people. Qualities of a Solid Thesis Statement: Focused; Arguable; Relevant; Complex; Needs further support and explanation 2. INTRODUCTIONS: Grab your reader’s attention; tell him or her what they need to know before embarking on the rest of your argument. Introductions can also lay out a map for how you will go about proving your argument. For this reason, usually the introduction is the LAST part of the paper you write. You may write an initial introduction to get the ball rolling, but once you complete your paper, you should go back and rewrite the intro. How can you know where your paper will go until you write it? Do not list all of your supporting evidence. Save the nitty-gritty details for the supporting paragraphs. The attention-getting hook at the beginning of your introduction should be an intriguing question or statement. It is not random, but instead relates directly to your topic. Avoid: hokey claims, clichés, obvious statements, or dictionary definitions. Do not spend time thinking of a hook at the outset. It is much easier once you have the paper written or mostly written. 3. MAIN BODY OR SUPPORTING PARAGRAPHS: The strength of an essay comes from detailed, in-depth explanation that braces your thesis statement. Remember, the thesis always requires supporting explanation. Paragraphs come in all shapes and sizes. There is no minimum or maximum sentence limit. A paragraph expresses some specific idea or piece of evidence about your argument, and is unified by that specific idea. If your thinking is complex (and it should be!) then essay writing will be an exciting dance of paragraphs. Generally speaking, a paragraph reaches its end when you have finished talking about a given specific point and are ready to move to the next piece of supporting evidence. Do not rush! Develop and explain your main idea sloooooowly, using concrete details as support. The name of the game is detail. Move slow, provide context, explain things, use specific details. Slooooow. 4. CONCLUSIONS: Think of the conclusion as a pushing forward of your argument, not a shutting down or a recapitulation of what you’ve already proven. Do not restate or summarize your argument. Do not repeat yourself. Instead, try to give your reader something further to think about. It is sometimes a good idea to ask additional questions in your conclusion. You want your argument to cause your reader to ponder things further, not think they’ve closed the lid on the subject. For example, if you were writing that paper about Malcolm Gladwell’s essay, you might in your conclusion reflect on whether all social networks are the same, or if maybe some are better for social action that others. Or you could ask the reader which they would prefer: a world in which it is easy to communicate but hard to stage revolution or the opposite? Ideas for further thinking and a sense that your argument matters, that’s what you’re after. Though, as was the case with your introductions, you want to avoid clichés and vague statements.