New Historicism and Race and Ethnic Studies 1

advertisement

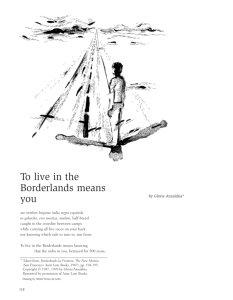

New Historicism and Race and Ethnic Studies 1 “New” vs. “Old” Historicism • “Old” Historicism – History provides the background and context for a story. – History is stable and objective. • Literature reflects or presents history. 2 “New” vs. “Old” Historicism • “Old” Historicism – History provides the background and context for a story. – History is stable and objective. • Literature reflects or presents history. • New Historicism – Both history and literature are complex and uncertain. – Need to consider multiple points of view and interpretations. • History and literature = cycle of mutual influence. (Make and remake each other.) 3 New Historicism • Move away from essentialism – History is a construction rather than an “essence” or truth. • E.g. One view= Christopher Columbus discovered America. • Another=Columbus was a brutal invader and conqueror. – It’s important to consider history from multiple viewpoints and to understand it as a “text.” 4 Race and Ethnic Studies • Overlaps with more specific focal points and areas: – – – – – South Asian Studies African Studies Latin American Studies Pacific Studies In the U.S.: • Asian American Studies, Latina/Latino studies (or Chicana/Chicano studies, depending on emphasis), American Indian Studies, African American Studies, Hawaiian Studies, etc. 5 “Zooming In”: Gloria Anzaldúa and Borderlands/La Frontera • Theorist in cultural studies, feminism, and queer theory • Borderlands/La Frontera – Emphasis on honoring or celebrating the mixing of national, racial, sexual, and gendered cultures and identities. – Language and Identity • Seamless movement between many different languages and dialects (multiple versions of English and Spanish, including Spanglish and Nahuatl) 6 Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa “So if you really want to hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity−I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself. Until I can accept as legitimate Chicano Texas Spanish, Tex-Mex, and all of the other languages that I speak, I cannot accept the legitimacy of myself. Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without always having to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, as as long as I have to accommodate English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate. I will no longer be made to be ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my serpent’s tongue−my woman’s voice, my sexual voice, my poet’s voice. I will overcome the tradition of silence” (81). Anzaldúa, Gloria Evangelina. Borderlands/La Frontera. 2nd Ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999. 7