North Seattle Community College Professor: Dawson Nichols

advertisement

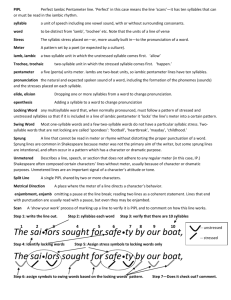

North Seattle Community College Theater 122, 123, 221, 222, 223 – Advanced Acting – Winter, 2011 Professor: Dawson Nichols E-mail: gnichols@sccd.ctc.edu Phone: 206/526-0196 appointment When: T,TH 11:00 – 1:15 Where: Library Building 1132A (Theatre) Office Hours: M & W, 8:00 – 9:45 & by This course is intended to assist advancing acting students in honing their craft. This quarter the course will focus on acting in classical plays, especially verse drama. We will be using two textbooks: Mastering Shakespeare: An Acting Class in Seven Scenes - Scott Kaiser – should be about $20 Playing Shakespeare: An Actor's Guide (Methuen Paperback) - John Barton – about $10 Also be prepared to acquire Shakespeare’s works. They can all be found online at http://shakespeare.mit.edu/, but I recommend getting physical copies if you can. The Arden editions have the best footnotes and explanatory materials, but others are cheaper. In the first weeks we will go through Kaiser’s book, scene by scene, exploring different aspects of classical speech and practicing with them through work on sonnets and speeches. We will study scansion, examine methods for speaking verse naturally, and incorporate verse into other acting processes. This is a laboratory class and depends on the active participation of every student. Course Objectives Through participation in this course students will learn Critical thinking through verse and script analysis and character development Expressivity through speaking verse in the context of characterization & performance Effective collaboration through scene work and staging exercises Strategies for tapping concentration, imagination and creativity Methodology through acting process and performance Students will learn experientially, through thoughtful analysis, participation, and constructive feedback. Expectations Students are expected to come to all classes prepared and willing to participate. This means that you have done the reading/rehearsing/memorizing for the class but it also means that you will be attentive and that you will participate in discussions. This is an active laboratory class, so you should come in comfortable clothes and shoes. If you are unable to attend a class for any reason, you are expected to call the theatre office. If you are going to miss a rehearsal for a scene, you are expected to call everyone affected to inform them. Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 2 Procedure Students will be involved in daily vocal and physical exercises. In the first weeks of the quarter we will be working with verse in speeches. Following this we will analyze, rehearse, and perform scenes from Shakespeare’s plays. See the following schedule for details. Assessment: For ease of scoring, this course will consist of 1000 points. Sonnet Scansion 5% Sonnet Performances (5% each) 10% Speech Scansion 5% Speech Performance 10% Scene One Scansion 10% Scene One Performance 20% Scene Two Scansion 10% Scene Two Performance 20% Participation 10% Total 100% 900 OR MORE = A 875-900=A- 850-874=B+ 800-850=B 700-749 = C 675-699=C- 650-674=D+ 600-649=D or 50 points or 100 points or 50 points or 100 points or 100 points or 200 points or 100 points or 200 points or 100 points or 1000 points 775-799=B- 750-774=C+ 575-599=D<574=F Schedule Date Assignments Due (and announcements) Subjects Week 1 January 4 January 6 Introductions – Acting Shakespeare Seminar Orchestrating speech (and action) Kaiser, Introduction and Scene 1 (Chapter 1) Audition Tomorrow for The New New News Week 2 January 11 Focal Points Kaiser, Scene 2 January 13 Images Kaiser, Scene 3 Sonnet Chosen Sonnet Scansion due Week 3 January 18 January 20 Subtext Action Kaiser, Scene 4 Kaiser, Scene 5 Sonnet performed expressively Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 3 Week 4 January 25 Toolkit Kaiser, Scene 6 Sonnet performed rhythmically Barton Chapters 1, 2, & 3 Verse Speech Chosen January 27 Week 5 February 1 Barton Chapters 4, 5, & 6 Verse speech scansion due February 3 Week 6 February 8 Barton Chapter 7 Verse speech performed First Scenes assigned February 10 Week 7 February 15 Barton Chapter 8 First scenes scansion due Rehearsal February 17 Week 8 February 22 February 24 Barton Chapter 9 First Scenes Performed Week 9 March 1 March 3 Barton Chapter 10 Second Scenes assigned Scansion work Week 10 March 8 Barton Chapter 11 Second Scenes scansion due March 10 Week 11 March 15 March 17 Barton Chapter 12 Second scenes performed Break Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 4 DAWSON’S SCANSION NOTES - THE BASICS Some actors feel that a general understanding of scansion is sufficient for their work. Speaking lines on stage is not, after all, poetical analysis, it is bringing a poem to life. The intention, the emotion, the feeling behind the lines – these are the important things. After all, actors are not English professors. Wrong. A good actor will analyze their lines with more rigor than an English Professor because a good actor recognizes that the life in the words is intricately linked to the shape and texture of the lines that the poet has written. The intention, the emotion, the feeling these are not behind the lines, they are in the lines. So an actor who speaks poetic lines without first having analyzed them is either lazy or stupid - probably both. So, let’s look at scansion. THE FEET Before you can understand feet, you have to understand the syllable. Syllables are the shortest phonetic unit usually consisting of a vowel or a vowel with one or more adjoining consonants. Many words have only one syllable: hi, no, me, tour, for, play. Put the last two examples together and you’ll have a two syllable word. Notice that there is a voiced vowel in each of the syllables in the two syllable word. This is always true. Again, every syllable has a vowel, and polysyllabic words have vowels in each of the syllables. For (1) Fortune (2) Fortunate (3) Fortunately (4) In speech, some syllables are stressed and some are not. The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables creates the rhythm of our speech. If we consciously regulate this pattern we are making poetry. (Notice that rhythm- or emphasis-based poetry depends entirely upon the spoken word.) The foot is the most basic poetic unit, consisting of a sequence of syllables in a specific rhythm. In English, there are six types of metrical feet: Iamb Trochee Pyrrhic Spondee Dactyl Anapest unstressed, stressed stressed, unstressed unstressed, unstressed stressed, stressed stressed, unstressed, unstressed unstressed, unstressed, stressed -/ /-// /---/ Most polysyllabic words have a normal rhythm of their own. Words like belief, hotel, police, and again are naturally spoken as iambs; that is, with the first syllable being unstressed and the second stressed. Similarly, words like senate, always, fortune, and hothouse are naturally trochees. Try to speak them the other way - you’ll see how much the rhythm is part of the word. Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 5 Because a word is naturally iambic does not mean that it will always make an iamb when it is used by a poet. Poe’s ‘The Raven’ begins: “Once, upon a midnight dreary... .” The word ‘upon’ is naturally iambic, but in this case the first syllable of the word is linked to the first word of the poem to complete a trochee, and the last syllable of the word begins the next trochee. Poets make use of the natural rhythm of words like puzzle pieces, linking their rhythms to those of the adjoining words in order to create the meter. THE METER Meter is simply the number and kind of feet that the author uses to create their lines. Each type of meter has its own character, and authors will choose a meter that is appropriate to their subject matter. Some give a sing-songy, childlike sense while others may seem aggressive. Iambic pentameter is the familiar Shakespearean base line, consisting of five iambic feet per line. “But hark, what light through yonder window breaks?” When we speak in English we tend to speak in iambs, so iambic pentameter is tremendously versatile – not to mention realistic. This is why the bard used it for plays. But while iambic pentameter is the most widely used meter, it should be recognized that there are a great many other types as well. Robert Frost was fond of iambic tetrameter (four iambic feet per line): “Whose woods are these? I think I know / His house is in the village though... .” And there is the familiar anapestic tetrameter dittie: “‘Twas the night before Christmas and all through the house / Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse.” And then, of course, there is Poe’s trochaic tetrameter (four trochees per line): “Once, upon a midnight, dreary, / While I pondered weak and weary... .” Notice too that while we speak in iambs, this is not a universal thing. Ancient Greeks, for instance, naturally spoke in dactyls. You’re probably aware of some dactylic Greek words that are still in use: theatre, orchestra, machina, parados, Ekkyklema. Naturally, Greek poets and playwrights used dactyls when they wrote, and when you read Oedipus or any other ancient tragedy you should be aware that the originals were written in dactylic hexameter. To identify the meter in which something is written in no way means that this rhythm should be slavishly followed without regard to the sense or feel of the words. As with music, most of the interesting things happens when the rhythm changes, picks up an offbeat, adds a quarter note, etc. This happens often. These changes are called substitutions, & this is where the interest is. So, to perform actual scansion you should: 1) Read the lines first for their sense only - their meaning. Make sure you understand the words, the allusions, the metaphors, then simply try to read it so that someone listening would understand what you’re saying. 2) Mark your reading. Which syllables did you stress, which did you not stress? Mark them as you read them without regard to the meter. Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 6 3) Examine your markings and see if the line conforms to the meter. Sometimes you’ll find that you’ve marked five iambs in the line. Great! The meter is regular and you’re probably making good sense of it. Move on to the next line. 4) When you find places where your emphasis for sense does not make five pretty iambs, figure out where the changes are and identify them. Is an iamb switched to a trochee? Is there a feminine ending? Sometimes the change won’t be obvious, or there may seem to be more than one option for the change. In these cases use these general rules: Make as few changes as possible. Unless you’re shouting spondees, try to limit the line to five stresses. It is VERY rare that Shakespeare will break out of the meter entirely in this way. Make it five feet if at all possible. Remember that feminine endings often add an 11th syllable to lines 5) Now that you have some substitutions identified, go back and try to read the line regularly. That is, see if the line would still make sense if it were read without the substitution you instinctively made. If it makes sense both ways you have a choice to make, and if you choose to not say the thing metrically, you must justify it. Generally such justifications take the form of psychological insight about the character – ‘he’s mad, so he starts with a spondee.’ (Note too that if the line does not make sense when spoken metrically, you still need to figure out why the author chose to make the change. Notice that this is a method that begins with your instinct and then forces you to challenge yourself and your habitual readings. This is the main benefit of scansion. It provides the poet with a method for collaborating with you on your character, and it provides you with a method of character development that can produce rich and diverse characterizations. Substitutions: There are a bazillion reasons why a line might divert from perfect iambic pentameter. For instance, initial trochees are often indicative of anger or surprise or interruption. The main thing to remember is that all substitutions and alterations in the meter are indications of something happening in the scene, usually something psychological. Yeah, Freud wasn't around yet, but Shakespeare was way ahead of the game. So, as you find your anapests and spondees, be aware that it's not just meter and rhythm— each substitution is a clue to the psychology of your character. Figure out why it's different and you've probably also figured out something about your character: how she reacts to anger, how he responds to stress, attitudes toward servants as opposed to peers, etc. Also, be aware that the five feet of a metrical line may be shared between two or more characters, as when Iago insinuates that Cassio isn’t honest: Othello: Iago: Othello: And went between us very oft. Indeed? Indeed? Ay, indeed! Discern'st thou aught in that? Is he not honest? Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Iago: Othello: Nichols Honest, my lord? Honest. 7 Honest? Ay, The first line of this sequence is perfect iambic pentameter, shared between Othello and Iago. When a line is shared like this the standard rule is that there should be no pause between the speakers: the second speaker should continue the rhythm established by the first and complete the line with dispatch. This makes sense here because Iago already knows what Othello is going to say, he's eager to get on with his manipulation, etc. Othello then picks right up with the next full line, eager to get the information. But when he poses his next question, the shared lines contain twelve beats which are difficult to reconcile into a metrical line. So, we can do one of two things: first, we can make the lines fit metrically, thusly: - - / / Is he not honest? / - - / Honest, my lord? A,T T, I T, F Iago: / Othello: Honest? Ay, In this reading we have an anapest and a trochee in the first line, a trochee and iamb in the second line, and a trochee and a feminine ending in the third. This may seem a torturous way of trying to justify the meter, but considering the tortured, extreme emotion in the scene it makes sense. And it allows the action to proceed without pauses, which could arguably kill the momentum of the scene. With this reading the actors can really attack the ends of each others' lines, the one because he is anxious about what he seems to be discovering and the other because he is eagerly nearing the fruition of his manipulations. Another reading would be to fill the metrical spaces with pauses. There can be no question that Shakespeare built in pauses, and many argue that the length of the pause is determined by how many feet are missing. As with music, you simply count the length of the rest and then proceed. Here we could place pauses between one or several of the lines, depending on how we want the scene to play. Pauses are certainly justified by the intense emotion of the scene, Othello's reluctance to hear what he knows is coming, Iago's relishing the moment or gauging Othello's reaction and proceeding cautiously, etc. Either one of these readings will work; the real point is that this method of analysis forces us to confront intentions, rationales, situations, character traits, etc. Unless we analyze the text and make ourselves aware of these different interpretations we will inevitably revert to our first readings, our habitual patterns, and we will not be making choices. This is the easiest thing to do, and it doesn't mean a necessarily bad reading or performance. What it does mean is that you are more likely to be playing yourself, the character Shakespeare wrote. This has great potential to diminish the play, and it can make a person a pretty boring performer. Finally, remember that this is not math – there is not only one correct reading. Scansion is a method for producing a variety of correct readings so that you can make interesting choices among them. Take the following simple phrase: Advanced Acting – Winter 2011 Nichols 8 I don’t think so. Try it as two trochees. Does it work? In what situation would you say it this way? What kind of character would say it this way? Try it as two iambs. Does it work? In what situation would this reading work? What kind of character does it convey? Try it as two spondees. Does it work? How about two pyrrhics? What kind of character would mumble like that? Now you have a tool for varying your readings, and as you vary your reading you will discover different characterizations. You will inevitably find readings that work that are different from your habitual way of reading. That is, you will begin to move beyond your own behavior – you will begin to act. OTHER TERMS A feminine ending is an unstressed syllable at the end of a line, often dovetailing into the next line and working the rhythm of the two lines together more intimately. A line is said to be end stop when there is some punctuation to close a thought at the end of a metrical line. A line is enjambed when there is no punctuation at the end and the sense of what is being said carries through into the next line. A caesura is a pause in the middle of a metrical line. Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds, consonance is the repetition of consonants, diastole is the lengthening of short syllable or the stressing of an unstressed syllable (to complete a metrical rhythm), whereas syncope is the omission of a syllable from a word. Irony is using a word opposite to one's intent. If this is done unintentionally it is also a malapropism. Anthypophoria is reasoning with oneself. Amphibology is confusion arising from construction (an unfortunate phrase for instance - not to be confused with equivocation, which is confusion arising from the use of a particular word). Oh, that's enough. Look for these things though - they all mean something.